1. Introduction and basic set theory PDF

Operations on sets

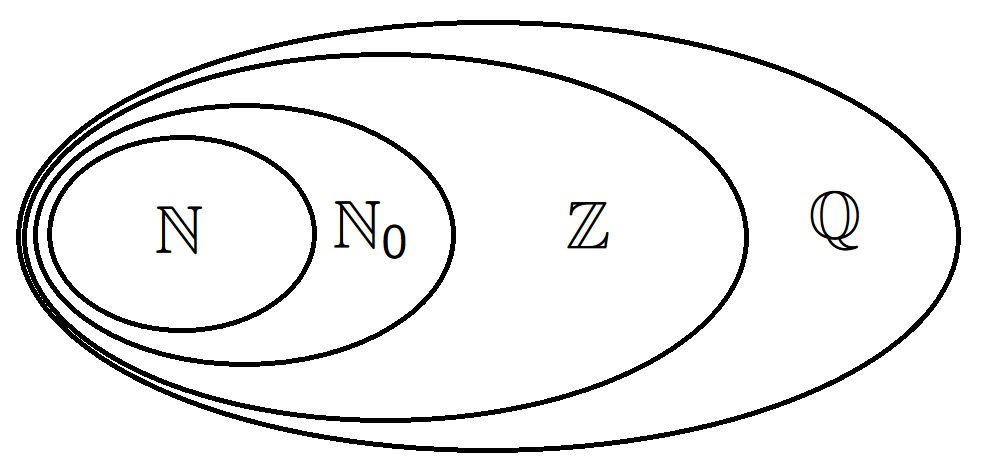

Number systems

\(\mathbb{N}=\mathbb Z_+=\{1,2,3,\ldots\}\) - positive integers,

\(\mathbb{N}_0=\{0,1,2,3,\ldots\}\) - non-negative integers,

\(\mathbb{Z}=\{\ldots,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,\ldots\}\) - the set of integers,

\(\mathbb{Q}=\{\frac{m}{n}: \,m \in \mathbb{Z}, n \in \mathbb{Z} \setminus \{0\}\}\) - the set of rationals.

Let \(a, d\in\mathbb Z\) and we say that \(d\) is a divisor of \(a\), and write \(d \mid a\), if there exists an integer \(q\in\mathbb Z\) such that \(a = dq\).

An integer \(n \in\mathbb Z\) is called prime if \(n > 1\) and if the only positive divisors of \(n\) are \(1\) and \(n\). The set of all prime numbers will be denoted by \(\mathbb P\).

Sets

The words family and collection will be used synonymously with "set".

Notation. \(\varnothing\)

- empty set,

\(\mathcal{P}(X)\) - family of subsets

of the set \(X\), sometimes called

power set of \(X\).

Example 1. If \(X=\{1\}\), then \[\mathcal{P}(X)=\{\varnothing, \{1\}\}.\]

Example 2. If \(X=\{1,2,3\}\), then \[\mathcal{P}(X)=\{\varnothing,\{1\},\{2\},\{3\},\{1,2\},\{1,3\},\{2,3\},\{1,2,3\}\}.\]

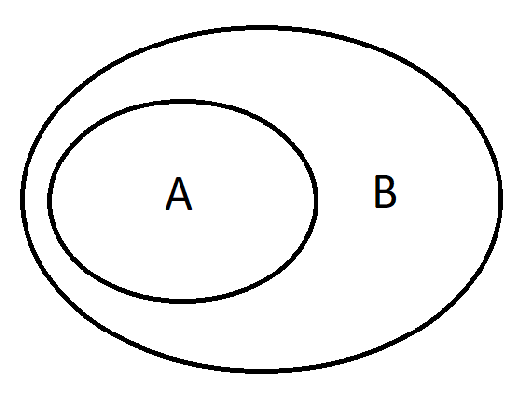

Inclusions 1/2

We write \(A \subseteq B\) if any element of \(A\) is also the element of \(B\).

We will write \(A \subset B\) if \(A \subseteq B\) and \(A \neq B\).

In practice, if one wants to prove that \(A = B\), it suffices to show that \(A \subseteq B\) and \(B \subseteq A\) hold simultaneously.

Inclusions 2/2

Example 1. We have \(\mathbb P\subset \mathbb N\subset \mathbb N_0\subset \mathbb Z\subset \mathbb Q\).

Example 2. If \(A=\{1,2\}\) and \(B=\{1,2,3\}\), then \(A \subseteq B\) and \(A \subset B\).

Example 3. If \(A=\{1,2,4\}\) and \(B=\{1,2,3\}\), then \(A \subseteq B\) does not hold, because \(4\) belongs to \(A\), but it does not belong to \(B\).

Union of sets 1/2

Union of sets. Let \(X\) be a set, \(\Sigma\) be a family of sets from \(\mathcal{P}(X)\). The union of the members from \(\Sigma\) is the following subset of \(X\): \[\bigcup_{E \in \Sigma}E=\{x \in X\;:\; x \in E \text{ for some }E \in \Sigma\}=\{x \in X\;:\; \exists_{E \in \Sigma} x \in E\}.\]

\(\exists \equiv\) there exists.

Union of sets 2/2

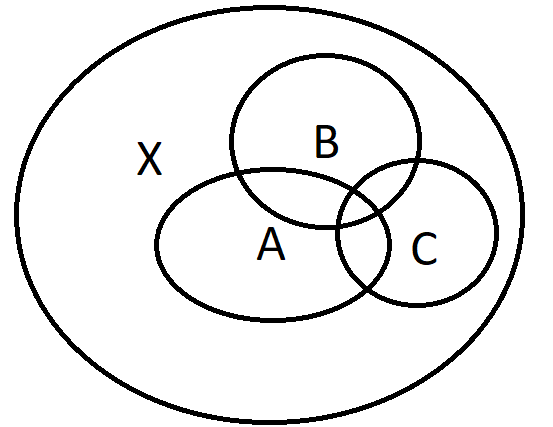

Example. If \(\Sigma=\{A,B,C\}\), then \(\bigcup_{E \in \Sigma}E=A \cup B \cup C\)

Intersection of sets 1/3

Intersection of sets. Let \(X\) be a set, \(\Sigma\neq\varnothing\) be a family of sets from \(\mathcal{P}(X)\). The intersection of the members from \(\Sigma\) is the following subset of \(X\): \[\bigcap_{E \in \Sigma}E=\{x \in X\;:\; x \in E \text{ for all }E \in \Sigma\}=\{x \in X\;:\; \forall_{E \in \Sigma} x \in E\}.\]

\(\forall \equiv\) for all.

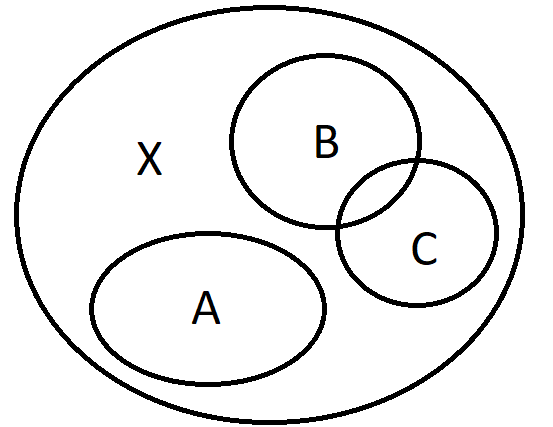

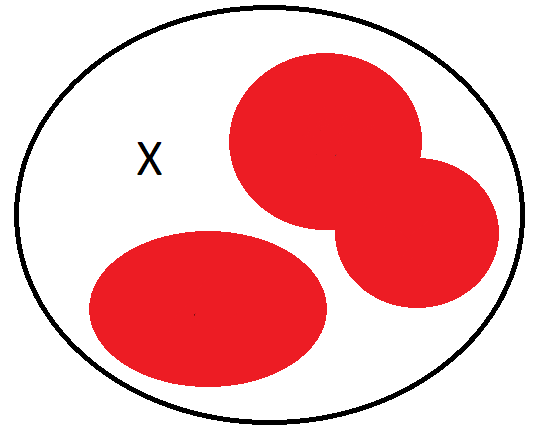

Intersection of sets 2/3

Example 1. If \(\Sigma=\{A,B,C\}\), then \(\bigcap_{E \in \Sigma}E=A \cap B \cap C\)

Intersection of sets 3/3

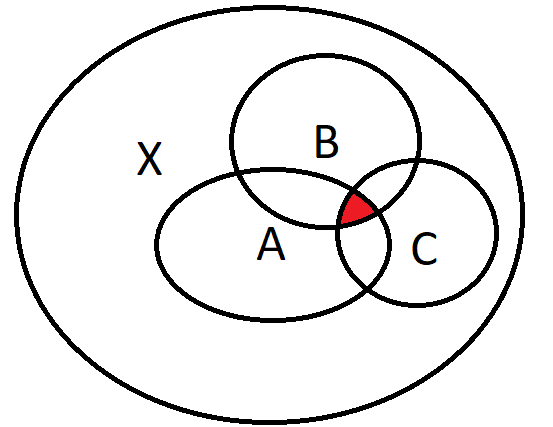

Example 2. If \(\Sigma=\{A,B,C\}\) as in the picture, then \(\bigcap_{E \in \Sigma}E=A \cap B \cap C=\varnothing\).

Union and intersection of indexed family of sets

If \(\Sigma=\{E_{\alpha}: \;\alpha \in A\}\), then the union and the intersection will be denoted respectively by

\[\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha} \text{ and }\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}.\].

Example 1. If \(A=\{1,2,3\}\), then \(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}=E_1 \cup E_2 \cup E_3\).

Example 2. If \(A=\mathbb{N}\), then \(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}=E_1 \cup E_2 \cup E_3 \cup E_4 \cup \ldots\).

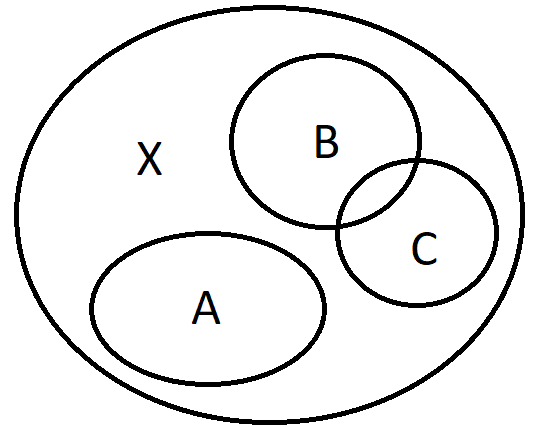

Disjointness

If \(A \cap B=\varnothing\), then we say that \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint.

Example. If \(A=\{1,2\}\), \(B=\{3,4\}\), \(C=\{1,2,3\}\), then \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint, but \(A\) and \(C\) are not disjoint.

Difference of sets

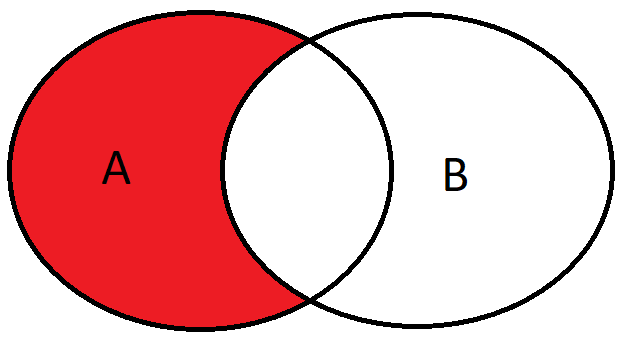

Difference of sets. If \(A,B\) are two sets, then \[A \setminus B=\{x \in A\;:\;x \not\in B\}.\]

Example 1. If \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) and \(B=\{3\}\), then \(A \setminus B=\{1,2\}\).

Example 2. If \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) and \(B=\{4\}\), then \(A \setminus B=\{1,2,3\}\).

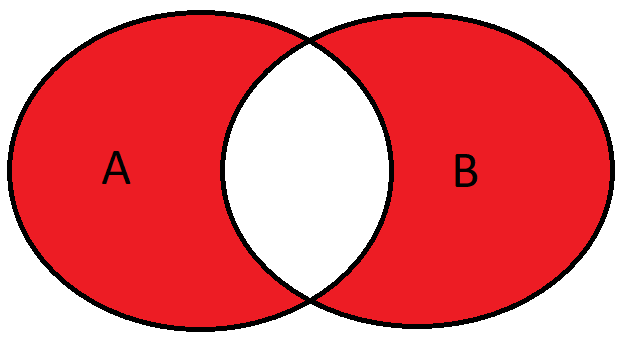

Symmetric difference of sets

Symmetric difference of sets. If \(A,B\) are two sets, then \[A \triangle B=(A \setminus B) \cup (B \setminus A)=(A \cup B) \setminus (A \cap B).\]

Example. If \(A=\{1,2,3,4\}\) and \(B=\{3,4,5,6\}\), then \(A \triangle B=\{1,2,5,6\}\).

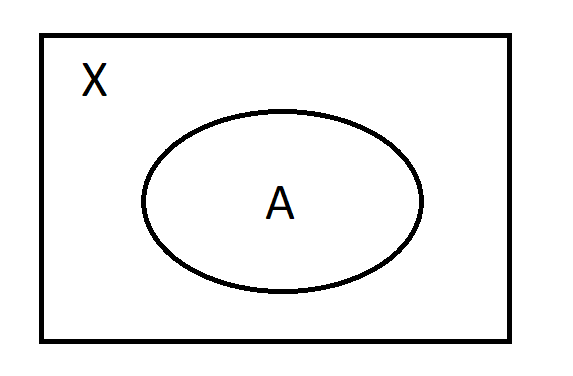

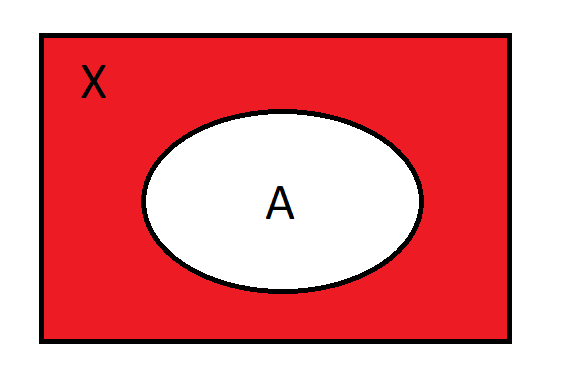

Complement of sets

Complement of sets. If a set \(X\) is given, and \(A \subseteq X\), then the complement of \(A\) in \(X\) is defined by \(A^c=X \setminus A\).

de Morgan’s laws

de Morgan’s laws. \[\left(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}\right)^c=\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}^c\] \[\left(\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}\right)^c=\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}^c\]

Example. We have \((A \cup B)^c=A^c \cap B^c\) and \((A \cap B)^c=A^c \cup B^c\).

Cartesian products, relations and functions

Ordered pairs

Ordered pairs. The ordered pair \((x, y)\) is precisely the set \(\{\{x\}, \{x, y\}\}\).

Theorem. \((x, y)=(u, v)\) iff \(x=u\) and \(y=v\).

Proof.

If \(x=u\) and \(y=v\), then \((x, y)=\{\{x\}, \{x, y\}\}=\{\{u\}, \{u, v\}\}=(u, v)\).

Suppose that \((x, y)=(u, v)\). This is equivalent to say that \[(x, y)=\{\{x\}, \{x, y\}\}=\{\{u\}, \{u, v\}\}=(u, v).\]

This implies that \(\{x\}=\{u\}\) and \(\{x, y\}=\{u, v\}\).

Hence \(x=u\) and \(y=v\) as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

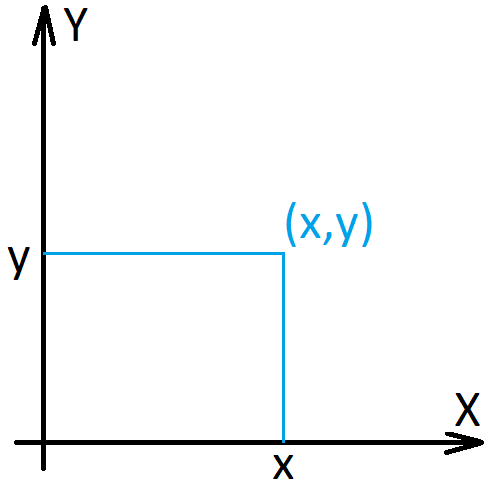

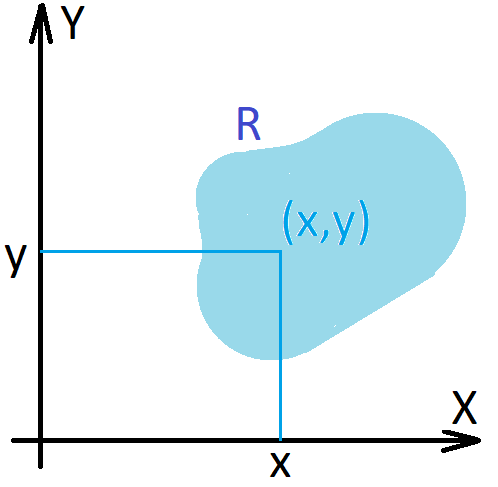

Cartesian products

Cartesian products. If \(X\) and \(Y\) are sets, their Cartesian product \(X \times Y\) is the set of all ordered pairs \((x,y)\) such that \(x \in X\) and \(y \in Y\).

\[X \times Y=\{(x,y)\;:\;x \in X,y \in Y \}\]

Cartesian products - examples

Example 1. If \(X=\{1,2,3\}, Y=\{4,5\}\), then \[X \times Y=\{(1,4),(2,4),(3,4),(1,5),(2,5),(3,5)\}.\]

Example 2. If \(X=\{1,2\}, Y=\{1,2\},\) then \[X \times Y=\{(1,1),(1,2),(2,1),(2,2)\}.\]

Example 3. If \(X \neq \varnothing\) and \(Y=\varnothing\), then \(X \times Y=\varnothing\).

Relations

Relations. A relation from \(X\) to \(Y\) is a subset \(R\) of \(X \times Y\), i.e. \(R\subseteq X \times Y\).

If \(X=Y\) we speak about relations on \(X\).

If \(R\) is a relation from \(X\) to \(Y\) we shall sometimes write \(xRy\) to mean that \((x,y) \in R \subseteq X \times Y\).

Relations - examples

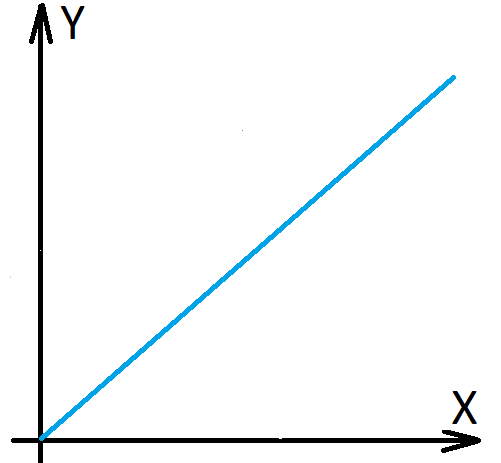

Example 1. If \(X=Y\) and we set \[xRy \iff x=y\]

This relation corresponds to the diagonal \(\Delta\) in \(X \times X\): \[\Delta=\{(x,x)\;:\;x \in X\} \subseteq X \times X.\]

Now we present more examples of relations.

More examples: functions and sequences

Functions. A function \(f:X \to Y\) is a relation \(R\) from \(X\) to \(Y\) with the property that for every \(x \in X\) there is a unique element \(y \in Y\) such that \(xRy\) in which case we write \[y=f(x).\]

Sequences. A sequence in \(X\) is a function from the natural numbers \(\mathbb N\) into the set \(X\). That is, it is an assignment of elements from \(X\) to natural numbers.

We usually denote such a function by \(\mathbb N\ni n\mapsto x_n\in X\), so the terms in the sequence are written \((x_1,x_2,x_3,\ldots)\).

To refer to the whole sequence, we will write \((x_n)_{n=1}^\infty\), or \((x_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\) or for the sake of brevity simply \((x_n)\).

Equivalence relations

Equivalence relations

Equivalence relations. An equivalence relation is a relation on \(X\) such that:

\(xRx\) for all \(x \in X\), (reflexivity).

\(xRy\) iff \(yRx\) for all \(x,y \in X\), (symmetry).

if \(xRy\) and \(yRz\), then \(xRz\) for all \(x,y,z \in R\). (transitivity).

Equivalence classes. An equivalence class of an element \(x\in X\) is the set \([x]=\{y \in X:xRy\}\).

Observe that \([x]\neq\varnothing\) for every \(x\in X\), since \(R\) is reflexive.

Properties of equivalence relations

Theorem. Let \(X\) be a set, with an equivalence relation \(R\) on \(X\). Then either \([x] = [y]\) or \([x]\cap [y]=\varnothing\) for any \(x,y\in X\).

Proof. Let \(x, y\in X\) and assume that there is some element \(z\in [x]\cap [y]\); in other words, \(xRz\) and \(yRz\). Now, let \(u\in[x]\). Since \(xRu\) and \(xRz\) then \(uRz\) by symmetry and transitivity. But \(yRz\), so again by symmetry and transitivity \(yRu\), which means that \(u\in [y]\). We have proved that \([x]\subseteq[y]\). Similarly we obtain the other inclusion \([y]\subseteq[x]\). Hence, \([x]=[y]\) if \([x]\cap [y]\neq\varnothing\) .

As an easy consequence we obtain the following important result.

Theorem. \(X\) is the disjoint union of the equivalence classes.

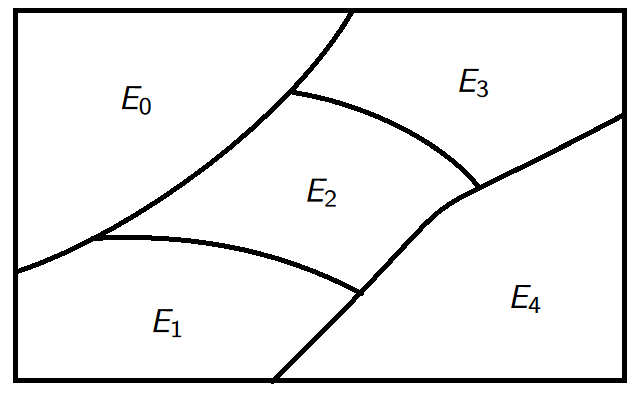

Equivalence relations - examples 1/2

Example. Let \(X=\mathbb{Z}\). Consider \[xRy \iff x \equiv y \mod 5 \iff 5|(x-y).\]

the equivalence classes corresponding to the relation \(R\) are the sets: \[\begin{aligned} E_0&=[0]=\{y\in\mathbb Z: 5|(0-y)\}=\{5k\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\},\\ E_1&=[1]=\{y\in\mathbb Z: 5|(1-y)\}=\{5k+1\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\},\\ E_2&=[2]=\{y\in\mathbb Z: 5|(2-y)\}=\{5k+2\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\},\\ E_3&=[3]=\{y\in\mathbb Z: 5|(3-y)\}=\{5k+3\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\},\\ E_4&=[4]=\{y\in\mathbb Z: 5|(4-y)\}=\{5k+4\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\}. \end{aligned}\]

Equivalence relations - examples 2/2

We have \[\mathbb{Z}=E_0 \cup E_1 \cup E_2 \cup E_3 \cup E_4.\]

Partially ordered sets

Partially ordered sets

Partial ordering. A partial ordering on a nonempty set \(X\) is a relation \(R\) on \(X\) with the following properties:

\(xRx\) for all \(x \in X\), (reflexivity).

If \(xRy\) and \(yRx\), then \(x=y\), (antisymmetry).

If \(xRy\) and \(yRz\), then \(xRz\), (transitivity).

Linear ordering. If \(R\) additionally satisfies that for all \(x, y\in X\) either \(xRy\) or \(yRx\), then \(R\) is called linear or total ordering on \(X\).

Example. The set of rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\) with the natural order \(\le\) is totally ordered set. We say that \(r\le s\) for \(r, s\in\mathbb Q\) iff \(s-r\ge 0\).

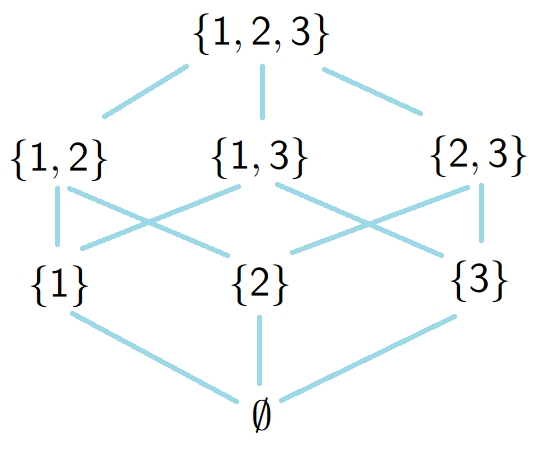

Examples of partial ordering

Example. If \(X\) is any set then \(P(X)\) is partially ordered by inclusion, i.e. \[ARB \iff A \subseteq B.\]

Consider \(X=\{1,2,3\}\) and we have its Hasse diagram

Poset \(\equiv\) partially ordered set

Poset. We say that \((X,\leq)\) is a poset if the relation “\(\leq\)” is a partial ordering on \(X\) or \((X,\leq)\) is partially ordered by “\(\leq\)”.

We will write \(x<y\) in a poset \((X,\leq)\) iff \(x \leq y\) and \(x\neq y\).

Upper (lower) bound. Let \((X,\leq)\) be a poset and \(A \subseteq X\). An element \(x \in X\) is an upper bound of \(A\) (resp. lower bound of \(A\)) if \(a \leq x\) for all \(a \in A\) (resp. \(x \leq a\) for all \(a \in A\)). An upper (lower) bound \(x\in X\) need not belong to \(A\).

Maximal (minimal) element. Let \((X,\leq)\) be a poset. A maximal (resp. minimal) element of \(X\) is an element \(x \in X\) such that if \(y \in X\) and \(x \leq y\) (resp. \(x \geq y\)) then \(x=y\).

Greatest (least) element. Let \((X,\leq)\) be a poset. A greatest (resp. least) element of \(X\) is an element \(x \in X\) such that \(y \leq x\) for all \(y \in X\) (resp. \(x \leq y\) for all \(y \in X\)).

Remark

Remark. In linearly (totally) ordered sets in contrast to general partially ordered sets

the greatest and maximal elements are the same,

the least and minimal elements are the same.

There may be many maximal and minimal elements in general partially ordered sets, and the maximal (minimal) elements are not comparable.

Example.

In order to see this we consider \(X=\mathcal P(\{1, 2, 3, 4\})\setminus \big\{\{1, 2, 3, 4\}\big\}\). The element \(\{1, 2, 3, 4\}\) is an upper bound for \(X\).

The set \(X\) does not have the greatest element, but the elements \(\{1, 2, 3\}, \{1, 2, 4\}, \{1, 3,4\}, \{2, 3, 4\}\) are maximal.

The empty set \(\varnothing\) is both the least and the minimal element for \(X\). The empty set \(\varnothing\) is a lower bound for \(X\).