12. Axiom of Choice, Cardinality, Cantor's theorem PDF

Partially ordered sets

Partially ordered sets

Partial ordering. A partial ordering on a nonempty set \(X\) is a relation \(R\) on \(X\) with the following properties:

\(xRx\) for all \(x \in X\), (reflexivity).

If \(xRy\) and \(yRx\), then \(x=y\), (antisymmetry).

If \(xRy\) and \(yRz\), then \(xRz\), (transitivity).

Linear ordering. If \(R\) additionally satisfies that for all \(x, y\in X\) either \(xRy\) or \(yRx\), then \(R\) is called linear or total ordering on \(X\).

Example. The set of rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\) with the natural order \(\le\) is totally ordered set. We say that \(r\le s\) for \(r, s\in\mathbb Q\) iff \(s-r\ge 0\).

Examples of partial ordering

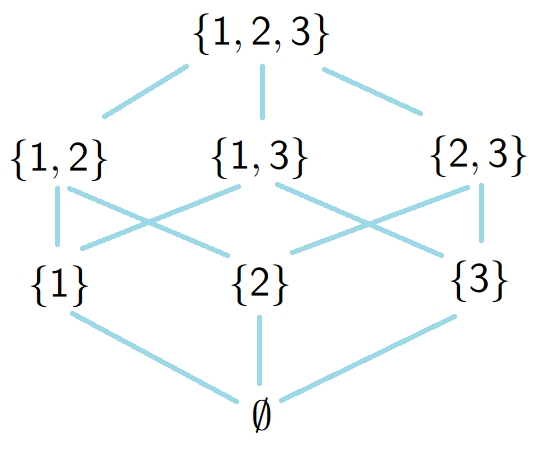

Example. If \(X\) is any set then \(\mathcal P(X)\) is partially ordered by inclusion, i.e. \[ARB \iff A \subseteq B.\]

Consider \(X=\{1,2,3\}\) and we have its Hasse diagram

Poset \(\equiv\) partially ordered set

Poset. We say that \((X,\leq)\) is a poset if the relation “\(\leq\)” is a partial ordering on \(X\) or \((X,\leq)\) is partially ordered by “\(\leq\)”.

We will write \(x<y\) in a poset \((X,\leq)\) iff \(x \leq y\) and \(x\neq y\).

Upper (lower) bound. Let \(A \subseteq X\), an element \(x \in X\) is an upper bound of \(A\) (resp. lower bound of \(A\)) if \(a \leq x\) for all \(a \in A\) (resp. \(x \leq a\) for all \(a \in A\)).

An upper (lower) bound \(x\in X\) need not to belong to \(A\) .

Maximal and greatest elements

Maximal (minimal) element. A maximal (resp. minimal) element of \(X\) is an element \(x \in X\) such that if \(y \in X\) and \(x \leq y\) (resp. \(x \geq y\)) then \(x=y\).

Greatest (least) element. A greatest (resp. least) element of \(X\) is an element \(x \in X\) such that \(y \leq x\) for all \(y \in X\) (resp. \(x \leq y\) for all \(y \in X\)).

Well ordered set. If \((X,\leq)\) is linearly ordered and every non-empty subset of \(X\) has a minimal element, which is necessarily unique, \(X\) is said to be well ordered by \(\leq\) and \(\leq\) is called well ordering on \(X\).

Examples.

\((\mathbb{N},\leq)\) is well ordered in contrast to \((\mathbb{Z},\leq)\) which is not well ordered.

Supremum and infimum of \(A\)

Supremum of \(A\). Let \(A\subseteq X\) be bounded above. We say that an element \(x_0 \in X\) is the least upper bound for \(A\) or the supremum of \(A\) (\(x_0=\sup A\)) if the following hold:

\(a \leq x_0\) for all \(a \in A\),

if \(a \leq x\) for all \(a \in A\), then \(x_0 \leq x\).

Infimum of \(A\). Let \(A\subseteq X\) be bounded below. We say that an element \(x_0 \in X\) is the greatest lower bound for \(A\) or the infimum of \(A\) (\(x_0=\inf A\)) if the following hold:

\(x_0 \leq a\) for all \(a \in A\),

if \(x \leq a\) for all \(a \in A\), then \(x \leq x_0\).

Four equivalent statements

If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a nonempty collection of nonempty sets, then \(\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing\).

Every partially ordered set has a maximal linearly ordered set, i.e. if \((X,\leq)\) is a poset there exists \(E \subseteq X\) that is linearly ordered by \(\leq\) such that no subset of \(X\) that properly includes \(E\) is linearly ordered by \(\leq\).

If \(X\) is partially ordered set and every linearly ordered subset of \(X\) has an upper bound, then \(X\) has a maximal element.

Every nonempty set \(X\) can be well ordered.

An auxiliary result

Let \((X,\leq)\) be a poset such that every linearly ordered subset of \(X\) has a supremum in \(X\). Then every function \(f:X \to X\) obeying \[x \leq f(x) \quad \text{ for all } \quad x \in X\] has a fixed point, i.e. there is \(x^{*} \in X\) such that \(f(x^{*})=x^{*}\).

Proof. Clearly the empty set \(\varnothing\) is linearly ordered so it has the supremum in \(X\), i.e. \(a=\sup \varnothing \in X\), which is the smallest element in \((X,\leq)\).

Let \(\mathcal{A} \subseteq \mathcal P(X)\) be the family of all \(A \subseteq X\) such that

\(a \in A\),

\(f[A] \subseteq A\),

if \(L \subseteq A\) is linearly ordered set in \((X,\leq)\), then \(\sup L \in A\).

Note that \(\mathcal{A} \neq \varnothing\) since \(X \in \mathcal{A}\). Then consider \[{\color{red}A_{*}=\bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}}A}.\]

It is easy to see that \(A_{*} \in \mathcal{A}\), equivalently \(A_{*}\) satisfies (a), (b), (c). \[f[A_{*}]=f\bigg[\bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}}A\bigg]\subseteq \bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}}f[A]\subseteq \bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}}A=A_{*}.\]

Our aim will be to prove that \(A_{*}\) is linearly ordered set in \((X,\leq)\).

Consider \[{\color{blue}B=\{x \in A_{*}: \text{ if }y \in A_{*} \text{ and } y<x \text{ then } f(y)\leq x\}}.\]

We shall show that \(B \in \mathcal{A}\).

Proof of (a) for \(B\). Observe that \(a \in B\) since \(a \in A_{*}\) and \(a\) is the smallest element of \((X,\leq)\), so there is no element \(y\) such that \(y<a\). Thus, \(a \in B\), hence (a) holds for \(B\).

Fix \(x \in B\) and define \[{\color{purple}B_{x}=\{z \in A_{*}\;:\;z \leq x \text{ or }f(x) \leq z\}\subseteq A_*}\]

We will show that \(B_{x} \in \mathcal{A}\) for all \(x \in B\).

Proof of (a) for \(B_x\). Note that \(a \in B_x\) since \(a \leq x\) for all \(x \in X\).

Proof of (b) for \(B_x\). Take \(z \in B_{x}\) and we show that \(f(z) \in B_x\). It will ensure that \(f[B_x] \subseteq B_x\). Since \(z \in B_{x}\) so \(z \leq x\) or \(f(x) \leq z\).

If \(z<x\) then \(f(z) \leq x\) by definition of \(B\), so \(f(z) \in B_x\).

Otherwise \(x=z\) or \(f(x) \leq z\). If \(x=z\) then \(f(z)=f(x)\) so \(f(z) \in B_{x}\). If \(f(x) \leq z\), then \[f(x) \leq z \leq f(z)\] thus we also have \(f(z)\in B_x\).

Proof of (c) for \(B_x\). Let \(L \subseteq B_{x}\) be a linearly ordered set. We will show that \(\sup L \in B_x\).

If all elements \(z \in L\) satisfy \(z \leq x\), then \(\sup L\le x\) and consequently \(\sup L \in B_x\).

If \(f(x) \leq z\) for some \(z \in L\), then \[f(x) \leq z \leq \sup L,\] then \(\sup L \in B_x\).

Thus we have proved that \(B_x \in \mathcal{A}\) for all \(x \in B\) since \[A_{*}=\bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}}A \subseteq B_x \subseteq A_{*}\] so \(B_x=A_{*}\) for all \(x \in B\). This means that \[{\color{blue} z \leq x \ \ \text{ or } \ \ f(x) \leq z \ \ \text{ for all } \ \ x \in B \ \ \text{ and } \ \ z \in A_{*}.} \qquad{\color{purple}(*)}\]

Proof of (b) for \(B\). Let \(x \in B\). We will show that \(f(x) \in B\). Recall \[{\color{blue}B=\{x \in A_{*}:\text{ if }y \in A_{*} \text{ and }y<x \text{ then }f(y)\leq x\}\subseteq A_*}.\]

Let \(y \in A_{*}\) be such that \(y<f(x)\). Then by (*) we have \(y \leq x\). If \(y<x\) then by the definition of \(B\) we have \[f(y) \leq x \leq f(x),\] so \(f(x) \in B\). If \(x=y\) then \(f(x)=f(y)\) and also \(f(x) \in B\).

Proof of (c) for \(B\). Let \(L \subseteq B\) be a linearly ordered set in \(B\). We will show that \(\sup L \in B\). Let \(y \in A_{*}\) be so that \(y<\sup L\), then there is \(x \in L\) such that \(x\not\leq y\). By (*) we have \(y<x\). By the definition of \(B\) one obtains \(f(y) \leq x\). Since \(x \in L\) then \(f(y) \leq x \leq \sup L\) thus \(\sup L \in B\) as desired.

We have proved that \(B \in \mathcal{A}\), hence \[A_{*}=\bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}}A \subseteq B \subseteq A_{*},\] thus \(B=A_{*}\).

Hence, by (*) for all \(x,z\in A_*=B\) we have \(z \leq x\) or \(f(x) \leq z\). So \[x \leq z \quad \text{ or } z \leq x.\]

Now it is easy to see that \(x_{*}=\sup A_{*} \in A_{*}\) by (c). Moreover, \(x_{*}\) is a fixed point of \(f\). Since by (b) we have \[x_{*} \leq \underbrace{f(x_{*})}_{\in A_{*}} \leq x_{*}=\sup A_{*}.\] Thus \(x_*=f(x_*)\) as claimed.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Auxiliary result

If \((X,\leq)\) is a poset such that every linearly ordered set has a supremum, then \(X\) contains a maximal element.

Proof. Suppose for a contradiction that there is no maximal element in \(X\). So for every \(x \in X\) there is \(y \in X\) such that \(x<y\). In other words, the sets \[A_{x}=\{y \in X : x<y\} \neq \varnothing.\]

Thus \(\prod_{x \in X}A_x \neq \varnothing\) by the axiom of choice. Now take \(f \in \prod_{x \in X}A_x\), then \(f(x) \in A_x\), so \(x<f(x)\). By the previous theorem \(x \leq f(x)\) for all \(x \in X\), hence there is \(x_{*}\in X\) such that \(x_{*}<f(x_{*})=x_{*}\), contradiction!$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The principles (A), (B), (C), and (D) are equivalent.

Proof (A) \(\Longrightarrow\) (B).

Principle (B) says that if \((X,\leq)\) is a poset then \(X\) has a maximal linearly ordered set.

Let \(\mathcal L\) be a set of all linearly ordered subsets in \((X,\leq)\). Note that \((\mathcal L, \subseteq)\) is a poset ordered by inclusion \(\subseteq\).

Let \(\mathcal{M} \subseteq \mathcal L\) be a linearly ordered set. It is easy to see that \[\mathcal S=\bigcup_{M\in \mathcal{M}}M\] is a linearly ordered set in \((X,\leq)\) and \(\mathcal S\) is the supremum for \(\mathcal{M}\).

Thus from the previous theorem there exists a maximal element \(L \in \mathcal L\) which is the maximal linearly ordered set in \((X,\leq)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (B) \(\Longrightarrow\) (C).

Principle (C) states that if \((X,\leq)\) is a poset and every linearly ordered subset of \(X\) has an upper bound, then \(X\) has maximal element.

By (B) there is a maximal linearly ordered set \(L \subseteq X\). From the assumption in (C) the set \(L\) has an upper bound in \(X\).

Let \(a \in X\) be the upper bound for \(L\). From maximality of \(L\) in \(X\) we must have that \(a \in L\), or else \(L\cup\{a\}\) contradicts the maximality of \(L\).

Then \(a\) is a maximal element of \(X\). If we take \(x \in X \setminus L\) such that \(a \leq x\), then \(a=x\). Otherwise we consider \(L \cup \{x\}\) which is linearly ordered set containing \(L\), and this contradicts the maximality of \(L\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (C) \(\Longrightarrow\) (D).

Principle (D) states that every nonempty set \(X\) can be well ordered. Let \(\mathcal{W}\) be the collection of well-orderings of subsets of \(X\) defined by \[\mathcal{W}=\{(E,\leq): E \subseteq X \text{ and } \leq \text{ is well ordering on }E\}\] and define the partial ordering on \(\mathcal{W}\) as follows: If the relations \(\leq_1\) and \(\leq_2\) are well orderings on \(E_1\) and \(E_2\) respectively, then \(\leq_1\) precedes \(\leq_2\) in the partial order if:

It is easy to see that the hypotheses of (C) are satisfied on \(\mathcal{W}\). We take \(\mathcal L \subseteq \mathcal{W}\) to be a linearly ordered set in \(\mathcal{W}\) and we note that \(\bigcup_{L\in\mathcal L} L\) is an upper bound for \(\mathcal L\). Then (C) implies that there is a maximal element \((E,\leq) \in \mathcal{W}\).

This must be a well ordering on \(X\) itself. If \(\leq\) is a well ordering on a proper subset \(E \subset X\) and \(x_0 \in X \setminus E\) then \(\leq\) can be extended to a well ordering on \(E \cup\{x_0\}\) by declaring that \(x \leq x_0\) for all \(x \in E\), but this is a contradiction since \((E,\leq)\) is a maximal element of \(\mathcal{W}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (D) \(\Longrightarrow\) (A).

Suppose that \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a nonempty collection of nonempty sets. Let \[X=\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}.\]

Using (D) we pick a well ordering on \(X\). For any \(\alpha \in A\) let \(f(\alpha)\) be the minimal element of \(X_\alpha\). Then \[\qquad \qquad f \in \prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing. \qquad \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Cardinality

Cardinality

Cardinality. If \(X\) and \(Y\) are nonempty sets, we define the expressions \[{\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y) \ \ \text{ {\color{red}(injective)}},\] \[{\rm card\;}(X) = {\rm card\;}(Y)\ \ \text{ {\color{red}(bijective)}},\] \[{\rm card\;}(X) \geq {\rm card\;}(Y) \ \ \text{ {\color{red}(surjective)}},\]

to mean that there exists \(f:X \to Y\) which is injective, bijective, surjective respectively.

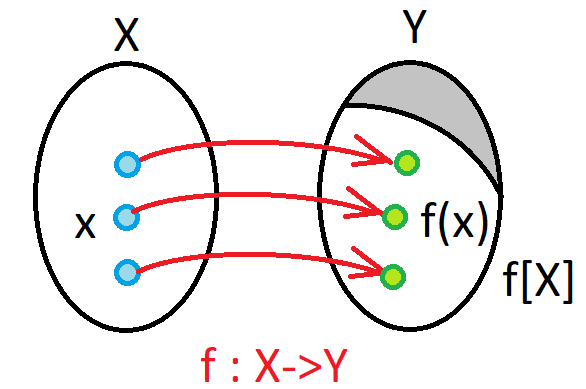

Cardinality - pictures 1/2

\({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y),\) (injective) ,.

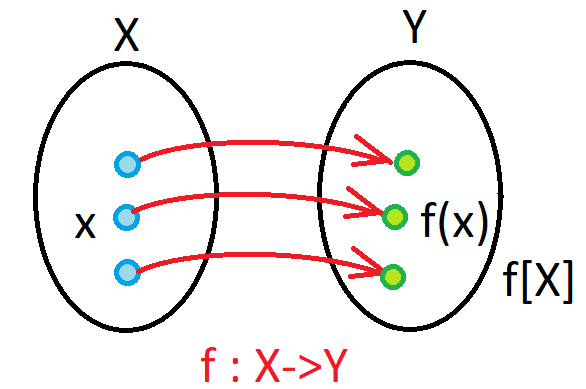

\({\rm card\;}(X) = {\rm card\;}(Y),\) (bijective).

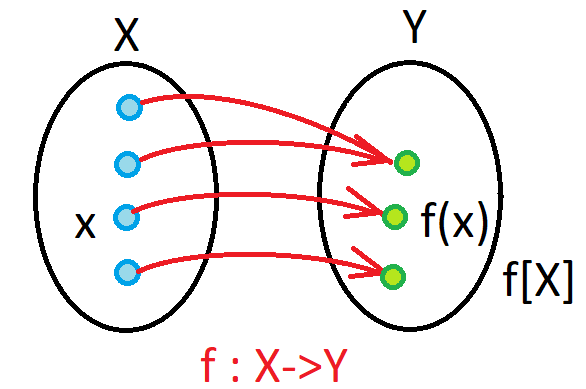

Cardinality - pictures 2/2

\({\rm card\;}(X) \geq {\rm card\;}(Y),\) (surjective).

We also define \({\rm card\;}(X)<{\rm card\;}(Y)\) to mean that there is an injection but not a bijection.

We also have \({\rm card\;}(\varnothing) < {\rm card\;}(X)\) and \({\rm card\;}(X)>{\rm card\;}(\varnothing)\) for all \(X \neq \varnothing\).

\({\rm card\;}(X)\) -example

Example. Let \[X=\{1,2,3,4,\ldots\}\] \[Y=\{101,102,103,\ldots,\}.\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution. Let us define \(f:X \to Y\) by \[f(x)=x+100,\] then \(f\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\({\rm card\;}(X)\) - example

Example. Let \[X=\{1,2,3,4,\ldots\}\] \[Y=\{1^2,2^2,3^2,4^2,\ldots,\}.\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution 1. Let us define \(f:X \to Y\) by \[f(x)=x^2,\] then \(f\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Solution 2. Let us define \(g: Y \to X\) by \[f(x)=\sqrt{x},\] then \(g\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Let \[X=\{1,2,3\}\] \[Y=\{2,4,6,8\}.\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)<{\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution. Note that \(f(x)=2x\) is an injection from \(X\) to \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y)\). On the other hand, any function from \(X\) to \(Y\) takes at most \(3\) values, so it is not a surjection, so \({\rm card\;}(X)<{\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Let \[X=[0,1]\] \[Y=[1,3].\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution. Let us define \(f:X \to Y\) by \[f(x)=2x+1,\] then \(f\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proposition

Proposition. We have \[{\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y) \iff {\rm card\;}(Y) \geq {\rm card\;}(X).\]

Proof (\(\Rightarrow\)). Assume that \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y)\). This means that there is an injection \(f:X \to Y\). Thus \(f\) is a bijection \(f:X \to f[X] \subseteq Y\). Let \(f^{-1}\) be the inverse \(f^{-1}:f[X] \to X\). Pick \(x_0 \in X\) and define \(g\) by

\[g(y)=\begin{cases}f^{-1}(y) \text{ if }y \in f[X],\\ g(y)=x_0 \text{ if }y \in Y \setminus f[X]. \end{cases}\].

Then we see that \(g\) is surjective from \(Y\) to \(X\).

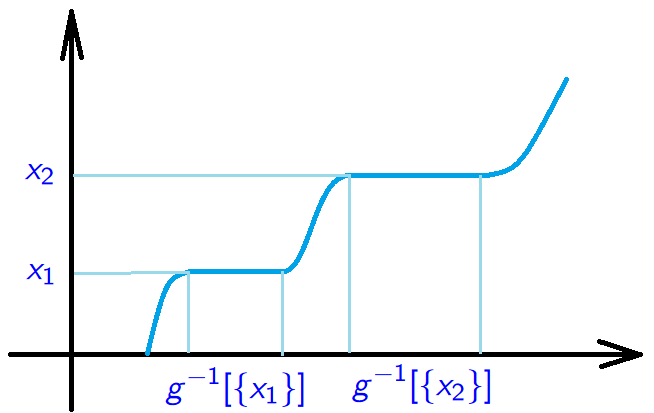

Proof (\(\Leftarrow\)). If \({\rm card\;}(Y) \geq {\rm card\;}(X)\), then there is a surjection \(g:Y \to X\). Then \(g[Y]=X\), and, consequently, \(g^{-1}[\{x\}]\) are nonempty and

\[g^{-1}[\{x_1\}] \cap g^{-1}[\{x_2\}] = \varnothing \quad\text{ if }\quad x_1 \neq x_2.\].

Using the axiom of choice the set \(\prod_{x \in X}g^{-1}[\{x\}] \neq \varnothing\). Taking \[f \in \prod_{x \in X}g^{-1}[\{x\}]\] we see that \(f\) is an injection from \(X\) to \(Y\). Indeed, if \(x_1 \neq x_2\), then \(f(x_1) \in g^{-1}[\{x_1\}]\) and \(f(x_2) \in g^{-1}[\{x_2\}]\), but \[g^{-1}[\{x_1\}] \cap g^{-1}[\{x_2\}] = \varnothing,\] thus \(f(x_1) \neq f(x_2)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$