19. Derivatives, the; Mean-Value Theorem and its Consequences; Higher Order Derivatives; Convex and Concave functions PDF

Differentiation

Derivative

Derivative. Let \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\). For any \(x \in [a,b]\) form the quotient function \[\phi(t)=\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}, \quad a<t<b, \quad t \neq x; \qquad \text{ and define}\] \[{\color{blue}f'(x)=\lim_{t \to x}\phi(t)}\] provided the limit exists. We thus associate with the function \(f\) a function \(f'\) whose domain is the set of points \(x\) for which the limit \(\lim_{t \to x}\phi(t)\) exists. The function \(f'\) is called the derivative of \(f\).

Differentable function.

If \(f'\) is defined at point \(x\), we say that \(f\) is differentiable at \(x\).

If \(f'\) is defined at every point of a set \(E \subseteq [a,b]\) we say that \(f\) is differentiable on \(E\).

Remarks – endpoints

Right-hand and left-hand limits.

It is possible to consider right-hand and left-hand limits of \(\phi(t)\).

This leads to the definition of right-hand and left-hand derivatives.

In particular, at the endpoints \(a,b\) the derivative exists if exists a right-hand and left-hand derivative respectively.

Endpoints.

If \(f\) is defined on a segment \((a,b)\) and if \(a<x<b\), then \(f'(x)\) is defined by \[\lim_{t \to x}\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x},\] but \(f'(a)\) and \(f'(b)\) are not defined in this case.

Example

Exercise 1. Using the definition, calculate the derivative of \(f(x)=x^2\) at a point \(x\).

Solution. We have \[\lim_{t \to x}\frac{t^2-x^2}{t-x}=\lim_{t \to x}x+t=2x.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Exercise 2. Using the definition, calculate the derivative of \(f(x)=x^3\) at a point \(x\).

Solution. Using the formula \(x^3-y^3=(x-y)(x^2+xy+y^2)\) we have \[\lim_{t \to x}\frac{t^3-x^3}{t-x}=\lim_{t \to x}x^2+xt+t^2=3x^2.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Exercise 3. Using the definition, calculate the derivative of \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\) at a point \(x\).

Solution. Using the formula

\[x-y=(\sqrt{x}-\sqrt{y})(\sqrt{x}+\sqrt{y}),\]. we obtain \[\lim_{t \to x}\frac{\sqrt{t}-\sqrt{x}}{t-x}=\lim_{t \to x}\frac{1}{\sqrt{t}+\sqrt{x}}=\frac{1}{2\sqrt{x}}.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Theorem

Theorem. If \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) is differentiable at \(x \in [a,b]\), then \(f\) is continuous at \(x\).

Proof. Note that \[f(t)-f(x)=\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}(t-x) \ _{\overrightarrow{t \to x}}\ f'(x) \cdot 0=0.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Remark 1. The converse of this theorem is not true.

Let \(f(x)=|x|\) but it is not differentiable at \(x=0\).

Remark 2. It is also possible to construct a continuous function on \(\mathbb{R}\) which is not differentiable at any point of \(\mathbb{R}\).

Arithmetic theorem for derivatives

Theorem. Let \(f,g:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) be differentiable at \(x \in [a,b]\). Then \(f+g\), \(f \cdot g\), and \(\frac{f}{g}\) are differentiable at \(x\) and we have

\((f+g)'(x)=f'(x)+g'(x)\),

\((fg)'(x)=f'(x)g(x)+f(x)g'(x)\),

\(\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)'(x)=\frac{f'(x)g(x)-f(x)g'(x)}{(g(x))^2}\), whenever \(g(x) \neq 0\).

Proof of (a). It is clear, since \[\begin{aligned} (f+g)'(x)=&\lim_{t \to x}\frac{f(t)+g(t)-f(x)-g(x)}{t-x}=\lim_{t \to x}\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}\\ &+\lim_{t \to x}\frac{g(t)-g(x)}{t-x}=f'(x)+g'(x).\qquad \end{aligned}\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Proof of (b). Let \(h=f \cdot g\), then \[h(t)-h(x)={\color{red}f(t)(g(t)-f(x))}+{\color{blue}f(x)(f(t)-g(x))}.\] Thus \[\begin{aligned} (f \cdot g)'(x)&=h'(x)=\lim_{t \to \infty}\frac{h(t)-h(x)}{t-x} \\ &={\color{red}\lim_{t \to x}f(t)\frac{g(t)-g(x)}{t-x}}+{\color{blue}\lim_{t \to x}g(x)\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}} \\&={\color{red}f(x)g'(x)}+{\color{blue}g(x)f'(x)}.\qquad \end{aligned}\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\] Proof of (c). Let \(h=\frac{f}{g}\) and observe \[\begin{aligned} \frac{h(t)-h(x)}{t-x} =\frac{1}{g(x)g(t)}\left(g(x)\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}-f(x)\frac{g(t)-g(x)}{t-x}\right). \end{aligned}\] Letting \(t \to x\) we obtain the desired claim. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Examples

Example 1. \(f(x)=c \in \mathbb{R}\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), then \(f'(x)=0\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Example 2. \(f(x)=x^n\), then \(f'(x)=nx^{n-1}\), \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). Indeed, \[x^n-y^n=(x-y)\left(x^{n-1}+x^{n-2}y+\ldots+xy^{n-2}+y^{n-1}\right),\] thus \[\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}=t^{n-1}+t^{n-2}x+\ldots+x^{n-2}t+x^{n-1} \to_{t \to x}nx^{n-1}.\]

Example 3. \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x^n}\), \(x \neq 0\), then \(f'(x)=-\frac{nx^{n-1}}{x^{2n}}=-\frac{n}{x^{n+1}}\).

Example 4. Every polynomial \(P(x)=\sum_{k=0}^na_kx^k\) is differentiable.

Example 5. Every \(R(x)=\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}\), where \(P\), \(Q\) are polynomials, is differentiable for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(Q(x) \neq 0\).

Exercise. Calculate \(f'(x)\), where \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}+3x^4+5.\)

Solution. Using the previous theorem and the fact that \[(\sqrt{x})'=\frac{1}{2\sqrt{x}}, \quad (x^4)'=4x^3, \quad (5)'=0,\] we obtain \(f'(x)=\frac{1}{2\sqrt{x}}+12x^3.\) $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Leibniz theorem

Theorem (Chain rule). Suppose that \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) is continuous and \(f'(x)\) exists at some point \(x \in [a,b]\), \(g\) is defined on an interval \(I\) which contains the range of \(f\) and \(g\) is differentiable at the point \(f(x)\). If \[h(t)=g(f(t)), \quad a \leq t \leq b,\] then \(h\) is differentiable at \(x\) and \[{\color{blue}h'(x)=g'(f(x))f'(x)}.\]

The latter identity is called the chain rule.

Let \(y=f(x)\). By the definition of the derivative we have \[f(t)-f(x)=(t-x)(f'(x)+u(t)),\] \[g(s)-g(y)=(s-y)(g'(y)+v(s)),\] where \(t \in [a,b]\), \(s \in I\), and \[\lim_{t \to x}u(t)=0 \qquad \text{ and }\qquad \lim_{s \to y}v(s)=0.\] Let \(s=f(t)\) and note that \[\begin{aligned} h(t)-h(x)&=g(f(t))-g(f(x))=(f(t)-f(x))(g'(y)+v(s))\\ &= (t-x)(f'(x)+u(t))(g'(y)+v(s)). \end{aligned}\]

If \(t \neq x\), then \[{\color{red}\frac{h(t)-h(x)}{t-x}=(g'(y)+v(s))(f'(x)+u(t))}.\] Letting \(t \to x\) we see \[s=f(t) \ _{\overrightarrow{t \to x}}\ f(x)=y\] by the continuity of \(f\). Thus \[\lim_{t \to x}\frac{h(t)-h(x)}{t-x}=g'(y)f'(x)=g'(f(x))f'(x).\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Example

Exercise. Calculate \(h'(x)\), where \[h(x)=(x^5+x^3)^{100}.\]

Solution. By the chain rule \[h={\color{red}f} \circ {\color{blue}g}, \quad {\color{red}f(x)=x^{100}}, \quad {\color{blue}g(x)=x^5+x^3},\] so \[f'(x)=100x^{99}, \quad \text{ and } \quad g'(x)=5x^4+3x^2,\] \[h'(x)=100(5x^4+3x^2)(x^5+x^3)^{99}.\]

Remark. Newton’s binomial formula could be also used to calculate \(h'(x)\), but the solution seems to be longer.

Mean-value theorems

Local minimum and maximum

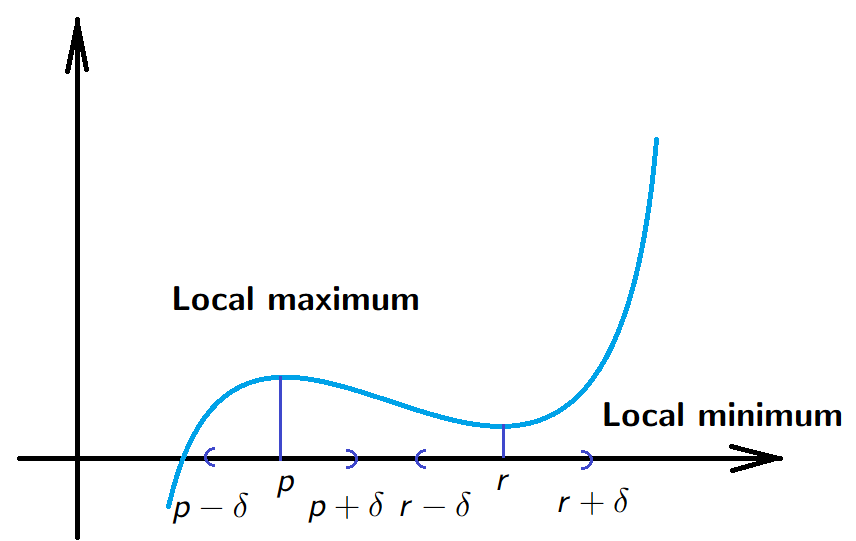

Local maximum and minimum. Let \(X\subseteq \mathbb R\) and \(f:X \to \mathbb{R}\). We say that \(f\) has a local maximum at the point \(p \in X\) if there exists \(\delta>0\) such that \[f(q) \leq f(p) \quad \text{ for all }\quad q \in (p-\delta, p+\delta),\]

Local minimum is defined likewise.

Theorem

Theorem. If \(f:[a, b]\to \mathbb R\) has a local maximum at \(x \in (a,b)\) and if \(f'(x)\) exists then \(f'(x)=0\). An analogous statement is also true for local minima.

Proof. If \(x \in (a,b)\) is a local maximum then there exists \(\delta>0\) such that if \(|q-x|<\delta\), then \(f(q) \leq f(x)\).

We can assume that \(a<x-\delta<x<x+\delta<b\) if \(x-\delta<t<x\), then \[\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x} \geq 0.\] Letting \(t \to x\) we see that \({\color{red}f'(x) \geq 0}\). If \(x<t<x+\delta\), then \[\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x} \leq 0.\]

Letting \(t \to x\) then we obtain \({\color{blue}f'(x) \leq 0}\), thus we conclude \({\color{violet}f'(x)=0}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The mean-value theorem

The mean-value theorem. If \(f,g:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) are continuous on \([a,b]\) and differentiable in \((a,b)\) then there is a point \(x \in (a,b)\) at which \[(f(b)-f(a))g'(x)=(g(b)-g(a))f'(x).\]

Note that differentiability is not required at the endpoints.

If \(g(x)=x\), we recover the Lagrange theorem.

Lagrange theorem. \[\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}=f'(x) \quad \text{ for some }\quad x\in (a,b).\]

For \(a \leq t \leq b\) consider \[h(t)=(f(b)-f(a))g(t)-(g(b)-g(a))f(t).\]

Then \(h\) is continuous on \([a,b]\) and \(h\) is differentiable in \((a,b)\) and \[h(a)=f(b)g(a)-f(a)g(b)=h(b).\]

To prove the theorem we have to show that \[\color{red}{h'(x)=0}\quad \text{ for some } \quad x \in (a,b).\]

If \(h\) is constant, this holds for every \(x \in (a,b)\).

Recall. A continuous function always attains its maximum and minimum on a compact set.

If \(h(t)>h(a)\) for some \(t \in (a,b)\), let \(x\) be a point in \([a,b]\) for which \(h\) attains its maximum.

Since \(h(a)=h(b)\) then \(x \in (a,b)\).

By the previous theorem \({\color{red}h'(x)=0}\), since \(h(x)=\sup_{y\in[a, b]}h(y)\).

Similarly, if \(h(t)<h(a)\) for some \(t \in (a,b)\) the same argument applies, and we choose \(x\in (a,b)\) where \(h\) attains its minimum.

This completes the proof of the theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example

Exercise. Assume that \(f\) is differentiable, moreover \[f(0)=1, \quad \ \ f(3)=2.\] Prove that there is \(c \in [0,3]\) such that \(f'(c)=\frac{1}{3}\).

Solution. By the mean-value theorem \[f(3)-f(0)=(3-0)f'(c)\] for some \(c \in (0,3)\). Moreover, by our assumption, \[{\color{red}1=}2-1=f(3)-f(0)=3f'(c),\] so \(f'(c)=\frac{1}{3}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem

Theorem. Suppose \(f\) is differentiable in \((a,b)\).

If \(f'(x) \geq 0\) for all \(x \in (a,b)\), then \(f\) is monotonically increasing.

If \(f'(x)=0\) for all \(x \in (a,b)\), then \(f\) is constant.

If \(f'(x) \leq 0\) for all \(x \in (a,b)\), then \(f\) is monotonically decreasing.

Proof. By the mean-value theorem for each \(a<x_1<x_2<b\) we have \[f(x_2)-f(x_1)=f'(x)(x_2-x_1)\quad \text{ for some }\quad x \in (x_1,x_2).\]

If \(f'(x) \geq 0\), then \(f(x_2) \geq f(x_1)\).

If \(f'(x)=0\), then \(f(x_2)=f(x_1)\).

If \(f'(x) \leq 0\), then \(f(x_2) \leq f(x_1)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark

Derivatives which exist at every point of an interval have an important property in common with functions which are continuous on the intervals:

their intermediate values are attained.

Theorem. Suppose that \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) is differentiable and suppose that \[f'(a)<\lambda<f'(b).\] Then there is a point \(x \in (a,b)\) such that \(f'(x)=\lambda\).

A similar result holds of course if \(f'(a)>f'(b)\).

Set \(g(t)=f(t)-\lambda t\).

Then \(g'(a)<0\) and \(g(t_1)<g(a)\) for some \(t_1 \in (a,b)\) since \[0>g'(a)=\lim_{a<t \to a}\frac{g(t)-g(a)}{\underbrace{t-a}_{{\color{red}>0}}}.\]

Similarly, since \(g'(b)>0\) we obtain \(g(t_2)<g(b)\) for some \(t_2 \in (a,b)\).

Hence \(g\) attains its minimum on \([a,b]\) at some point \(x \in (a,b)\).

Hence we have \({\color{red}g'(x)=0}\), so \(f'(x)=\lambda\) and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark. If \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) is differentiable then \(f'\) cannot have any simple discontinuity on \([a,b]\). But \(f'\) may have discontinuities of the second kind.

L’Hôpital’s rule

L’Hôpital’s rule

L’H ô pital’s rule. Suppose that \(f,g:(a,b) \to \mathbb{R}\) are differentiable in \((a,b)\) and \(g'(x) \neq 0\) for all \(x \in (a,b)\), where \(-\infty \leq a < b\leq +\infty\). Suppose that \[\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad\frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)} \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ A. \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{purple}(*)}\]

If \(f(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ 0\) and \(g(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ 0\), or

if \(g(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ +\infty\), then

\[\frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ A.\]

Remark. An analogous statement is true if \(x \to b\) or if \(g(x) \to -\infty\).

Proof. We first consider the case \(-\infty \leq A<+\infty\).

Choose a real number \(q\) such that \(A<q\) and then choose \(r\) such that \({\color{blue}A<r<q}\).

By (*) there is \(c \in (a,b)\) such that \(a<x<c\) implies \[\frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}<r.\]

If \(a<x<y<c\) then the mean-value theorem shows that there is a point \(t \in (x,y)\) such that

(**). \[\frac{f(x)-f(y)}{g(x)-g(y)}=\frac{f'(t)}{g'(t)}<r.\]

If \(f(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ 0\) and \(g(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ 0\) then we see

\[\frac{f(y)}{g(y)} \leq r<q, \quad \text{whenever} \quad a<y<c.\]

If \(g(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ +\infty\). Keeping \(y\) fixed in (**) we can choose a point \(c_1 \in (a,y)\) such that \(g(x)>g(y)\) and \(g(x)>0\) if \(a<x<c_1\). Then \[\frac{g(x)-g(y)}{g(x)}>0.\]

Thus \[\begin{aligned} \frac{f(x)-f(y)}{g(x)}&=\frac{f(x)-f(y)}{g(x)-g(y)}\frac{g(x)-g(y)}{g(x)}\\ &<r\frac{g(x)-g(y)}{g(x)}=r-\frac{g(y)}{g(x)}r. \end{aligned}\]

Hence \[\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}<r-r\frac{g(y)}{g(x)}+\frac{f(y)}{g(x)}, \quad \text{whenever} \quad a<x<c_1.\]

If we let \(x \to a\) (since \(g(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to a}}\ +\infty\)) we find \(c_2 \in (a,c_1)\) such that

\[\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}<q, \quad \text{ whenever }\quad a<x<c_2.\]

We conclude that for any \(q>A\) there is \(c_2\) such that

\[a<x<c_2 \quad \text{ implies } \quad \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}<q.\]

In the same manner if \(-\infty<A \leq +\infty\) and \(p\) is chosen so that \(p<A\) we can find a point \(c_3\) such that

\[a<x<c_3 \quad \text{ implies } \quad p<\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}.\]

If \(-\infty<A<+\infty\) we take \(\varepsilon>0\) and set \(p=A-\varepsilon\), \(q=A+\varepsilon\).

Then there is \(c_3\) so that for \(a<x<c_3\) we have \[A-\varepsilon<\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}<A+\varepsilon.\]

This completes the proof of the L’Hôpital rule.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Inverse functions

Theorem

Theorem. Let \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) be continuous and strictly increasing function. Then the inverse function of \(f\) is continuous and also strictly increasing.

Proof. Since \(f\) is continuous from the intermediate value theorem we know that the image of \(f\) is an interval, say \([\alpha,\beta]=f\big[[a,b]\big]\).

Let \(g: [\alpha,\beta]\to [a, b]\) be the inverse function. It is clear that \(g\) is also strictly increasing. We have to prove that \(g\) is continuous.

Let \(\gamma \in [\alpha,\beta]\). Given \(\varepsilon>0\) and \(\gamma=f(x)\) consider the closed interval \([x_1,x_2]\), where \[x_1=\begin{cases}c-\varepsilon &\text{ if }a \leq c-\varepsilon \\ a &\text{ otherwise }\end{cases}, \qquad x_2=\begin{cases}c+\varepsilon &\text{ if }c+\varepsilon \leq b \\ b &\text{ otherwise }\end{cases}.\] Then \(f(x_1) \leq f(x_2)\).

We assume \(a<b\). We select \[\delta=\min(f(x_2)-f(c),f(c)-f(x_1)).\]

Suppose that \(\delta>0\). If \(|y-\gamma|<\delta\), then there is unique \(x\) such that \(y=f(x)\) and \(x_1<x<x_2\) and hence \(|g(x)-c|<\varepsilon\).

If \(\delta=0\), then either \(a=c\) or \(b=c\), that is \(c\) is an endpoint.

Say \(c=a\). In this case we disregard \(x_1\) and let \(\delta=f(x_2)-f(c)\).

The same argument works if \(c=b\) (we let \(\delta=f(c)-f(x_1)\)). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem. Let \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) be continuous and \(a<b\). Assume that \(f\) is differentiable on \((a,b)\) and \(f'(x)>0\) for \(x \in (a,b)\). Then the inverse function \(g\) of \(f\) defined on \([\alpha,\beta]=f\big[[a,b]\big]\) is differentiable on \((\alpha,\beta)\) and

\[{\color{blue}g'(y)=\frac{1}{f'(x)}=\frac{1}{f'(g(y))}}\quad \text{ for }\quad y \in (\alpha,\beta).\]

Proof. Let \(\alpha < y_0<\beta\) and \(y_0=f(x_0)\) and \(y=f(x)\). Then \[\frac{g(y)-g(y_0)}{y-y_0}=\frac{x-x_0}{f(x)-f(x_0)}=\frac{1}{\frac{f(x)-f(x_0)}{x-x_0}} \ _{\overrightarrow{y \to y_0}}\ \frac{1}{f'(x_0)}=\frac{1}{f'(g(y_0))}.\]

If \(y \to y_0\) then \(x \to x_0\) since \(g\) is continuous.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Derivatives of higher order

Derivatives of higher order

Second derivative. If \(f\) has a derivative \(f'\) on an interval and if \(f'\) is itself differentiable, we denote the derivative of \(f'\) by \(f''\) and call \(f''\) the second derivative of \(f\).

Continuing this way, we obtain: \[f,f',f'',f^{(3)},\ldots,f^{(n)},\ldots\] each of which is derivative of the proceeding one.

\(f^{(n)}\) is called the \(n\)-th derivative, or derivative of order \(n\) of \(f\).

Remark.

In order for \(f^{(n)}(x)\) to exists at point \(x\), \(f^{(n-1)}(t)\) must exists in a neighbourhood of \(x\) (or in a one-sided neighborhood, if \(x\) is an endpoint of the interval on which \(f\) is defined) and \(f^{(n-1)}\) must be differentiable at \(x\).

Examples

Example. Consider \(f(x)=x^n\) for \(n\in\mathbb N\). Then \[f'(x)=nx^{n-1},\] \[f''(x)=n(n-1)x^{n-2},\] \[f'''(x)=n(n-1)(n-2)x^{n-3},\] \[\vdots\]

\[f^{(n)}(x)=n!.\]

Convexity

Convex functions

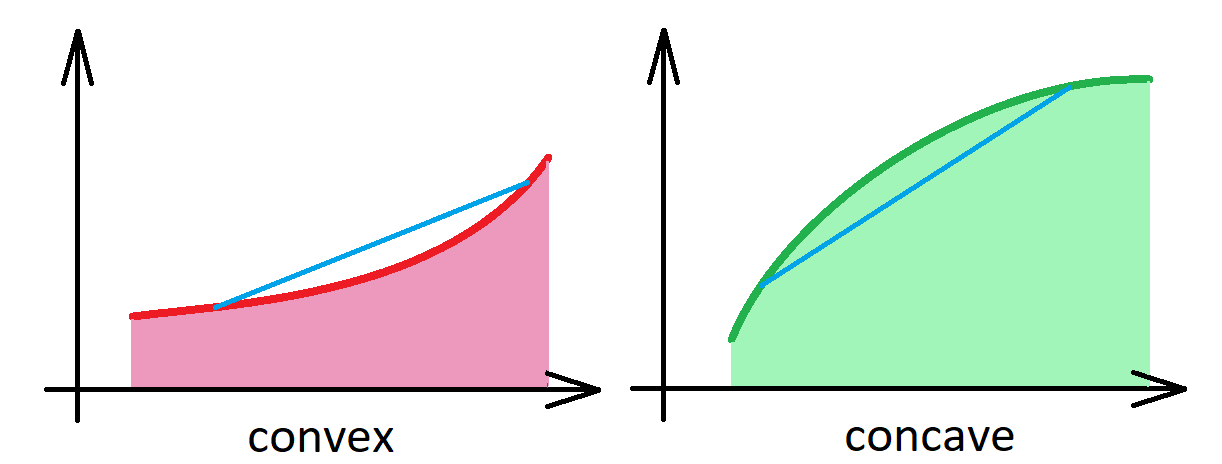

Convex function. A function \(f:(a,b) \to \mathbb{R}\) is convex if for every \(x, y\in(a, b)\) one has \[{\color{blue}f(\alpha x+\beta y) \leq \alpha f(x)+\beta f(y)}\] whenever \(\alpha,\beta \in [0,1]\) and \(\alpha+\beta=1\).

Observation 1. If \(f:(a,b) \to \mathbb{R}\) is convex and if \(a<s<t<u<b\), then \[\frac{f(t)-f(s)}{t-x} \leq \frac{f(u)-f(s)}{u-s} \leq \frac{f(u)-f(t)}{u-t} .\]

Proof. Since \(s<t<u\) then we may write \(t=\alpha u+\beta s\) for some \(\alpha,\beta \in [0,1]\) and \(\alpha+\beta=1\).

More precisely, \[t=\alpha u +\beta s=\underbrace{\frac{t-s}{u-s}}_{{\color{red}=\alpha}}u+\underbrace{\frac{u-t}{u-s}}_{{\color{red}=\beta}}s.\] Then by the convexity \[f(t)=f\left(\frac{t-s}{u-s}u+\frac{u-t}{u-s}s\right) \leq \frac{t-s}{u-s}f(u)+\frac{u-t}{u-s}f(s).\]

Hence \[f(t)-f(s) \leq \frac{t-s}{u-s}f(u)+\frac{u-t}{u-s}f(s)-\frac{u-s}{u-s}f(s),\] so \[f(t)-f(s) \leq \frac{t-s}{u-s}f(u)-\frac{t-s}{u-s}f(s).\] Hence \[\frac{f(t)-f(s)}{t-s} \leq \frac{f(u)-f(s)}{u-s}.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Observation 2

Observation 2. If \(f:(a,b) \to \mathbb{R}\) is convex then for any \(\lambda_1,\ldots,\lambda_n \in [0,1]\) satisfying \[\lambda_1+\lambda_2+\ldots+\lambda_n=1,\] we have \[f(\lambda_1x_1+\ldots+\lambda_nx_n) \leq \lambda_1f(x_1)+\ldots+\lambda_nf(x_n).\]

Proof. For \(n=2\) if follows from definition of convexity. Suppose that the statement is true for \(n \geq 2\) and we show it also holds for \(n+1\). Let \(\lambda_1,\ldots,\lambda_{n+1} \in [0,1]\) so that \(\lambda_1+\ldots+\lambda_{n+1}=1.\) Note that

(*). \[\sum_{k=1}^n \frac{\lambda_k}{1-\lambda_{n+1}}=\frac{1}{1-\lambda_{n+1}}\sum_{k=1}^n\lambda_k=\frac{1-\lambda_{n+1}}{1-\lambda_{n+1}}=1.\]

Then \[\begin{aligned} &f(\lambda_1x+\ldots+\lambda_{n+1}x_{n+1})\\&=f\left(\lambda_{n+1}x_{n+1}+(1-\lambda_{n+1})\left(\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{\lambda_k}{(1-\lambda_{n+1})}x_{k}\right)\right) \\&\underbrace{ \leq}_{{\color{red}\text{convexity}}}\lambda_{n+1}f\left(x_{n+1}\right)+(1-\lambda_{n+1})f\left(\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{\lambda_k}{(1-\lambda_{n+1})}x_{k}\right) \\&\underbrace{\leq}_{{\color{red}\text{induction+(*)}}}\lambda_{n+1}f\left(x_{n+1}\right)+(1-\lambda_{n+1})\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{\lambda_k}{(1-\lambda_{n+1})}f(x_{k}) \\&=\sum_{k=1}^{n+1}\lambda_{k}f(x_k).\qquad \end{aligned}\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Convexity and continuity

Theorem. If \(f:(a,b) \to \mathbb{R}\) is convex then \(f\) is continuous on \((a,b)\).

Proof. Let \(a<s<u<v<t<b\). By Observation 1 one has \[f(u) \leq f(s)+\frac{f(v)-f(s)}{v-s}(u-s)\] and also \[f(v) \leq f(u)+\frac{f(t)-f(u)}{t-u}(v-u).\] Thus \[\begin{aligned} f(s)+\frac{f(u)-f(s)}{u-s}(v-s) \leq f(v) \leq f(u)+\frac{f(t)-f(u)}{t-u}(v-u). \end{aligned}\] Take \(v=v_n\) for \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). If \(v_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ u\) converges to \(u\) we see that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}f(v_n)=f(u)\) thus \(\lim_{x \to u}f(x)=f(u)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Sign of the second derivative

The sign of the first derivative has been interpreted in terms of a geometric property of the function whether it is decreasing or increasing. We shall interpret the sign of the second derivative.

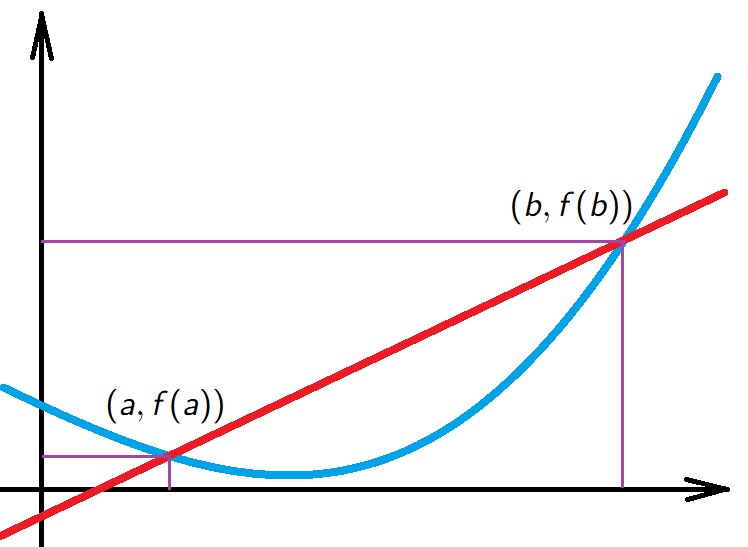

Let \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\), then the equation of the line passing through \((a,f(a))\) and \((b,f(b))\) is \[y=f(a)+\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}(x-a).\]

The condition that every point on the curve \(y=f(x)\) lies below the line segment between \(x=a\) and \(x=b\) is that \[f(x) \leq f(a)+\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}(x-a) \quad \text{ for } \quad a \leq x \leq b. \qquad \qquad {\color{purple}(*)}\]

Any point \(x\) between \(a\) and \(b\) can be written in the form \(x=a+t(b-a)\) with \(t \in [0,1]\). In fact, one sees that the map \[t \to a+t(b-a)\] is a strictly increasing bijection between \([0,1]\) and \([a,b]\).

If we substitute the value of \(x\) in terms of \(t\) in (*) we find an equivalent inequality \[{\color{blue}f((1-t)a+tb) \leq (1-t)f(a)+tf(b)},\] which is convexity of the function \(f\) on \((a,b)\).

Second derivative test

Theorem. Let \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) be continuous. Assume that \(f''\) exists on \((a,b)\) and \(f''(x) >0\) on \((a,b)\). Then \(f\) is strictly convex on the interval \([a,b]\).

Proof. For \(a<x<b\) we define \[g(x)=f(a)+\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}(x-a)-f(x).\] By the mean-value theorem we obtain \[g'(x)=\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}-f'(x)=f'(c)-f'(x) \quad \text{ for some }\quad a<c<b.\] Using the mean-value theorem again for \(f'\) we find \({\color{red}g'(x)=f''(d)(c-x)}\) for some \(d\) between \(c\) and \(x.\)

If \(a<x<c\), and using \(f''(d)>0\) we conclude that \(g\) is strictly increasing on \([a,c]\).

If \(c<x<b\) we conclude that \(g\) is strictly decreasing on \([c,b]\).

Since \(g(a)=0\) and \(g(b)=0\) it follows \(g(x)>0\) when \(a<x<b\), thus \[f(x)<f(a)+\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}(x-a).\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Concave function. A function \(f:(a,b) \to \mathbb{R}\) is concave if for every \(x, y\in(a, b)\) one has \[{\color{blue}f(\alpha x+\beta y) \geq \alpha f(x)+\beta f(y)}\] whenever \(\alpha,\beta \in [0,1]\) and \(\alpha+\beta=1\).

Analogues of all above-proved theorems hold for concave functions in place of convex functions.

Convex and concave functions