23. Uniform Convergence of a Sequence of Functions; Uniform Convergence and Differentiation; Series of Functions; The Weierstrass Approximation Theorem PDF

Pointwise and uniform convergence

Pointwise convergence

Pointwise convergence. For each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) let \(f_n:A \to \mathbb{R}\), where \(A \subseteq X\). The sequence \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) of functions converges pointwise on \(A\) to a function \(f\) if, for all \(x \in A\), the sequence of real numbers \((f_n(x))_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges to \(f(x)\). We write \[{\color{blue}\lim_{n \to \infty}f_n(x)=f(x) \quad \text{ or }\quad f_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ f}.\]

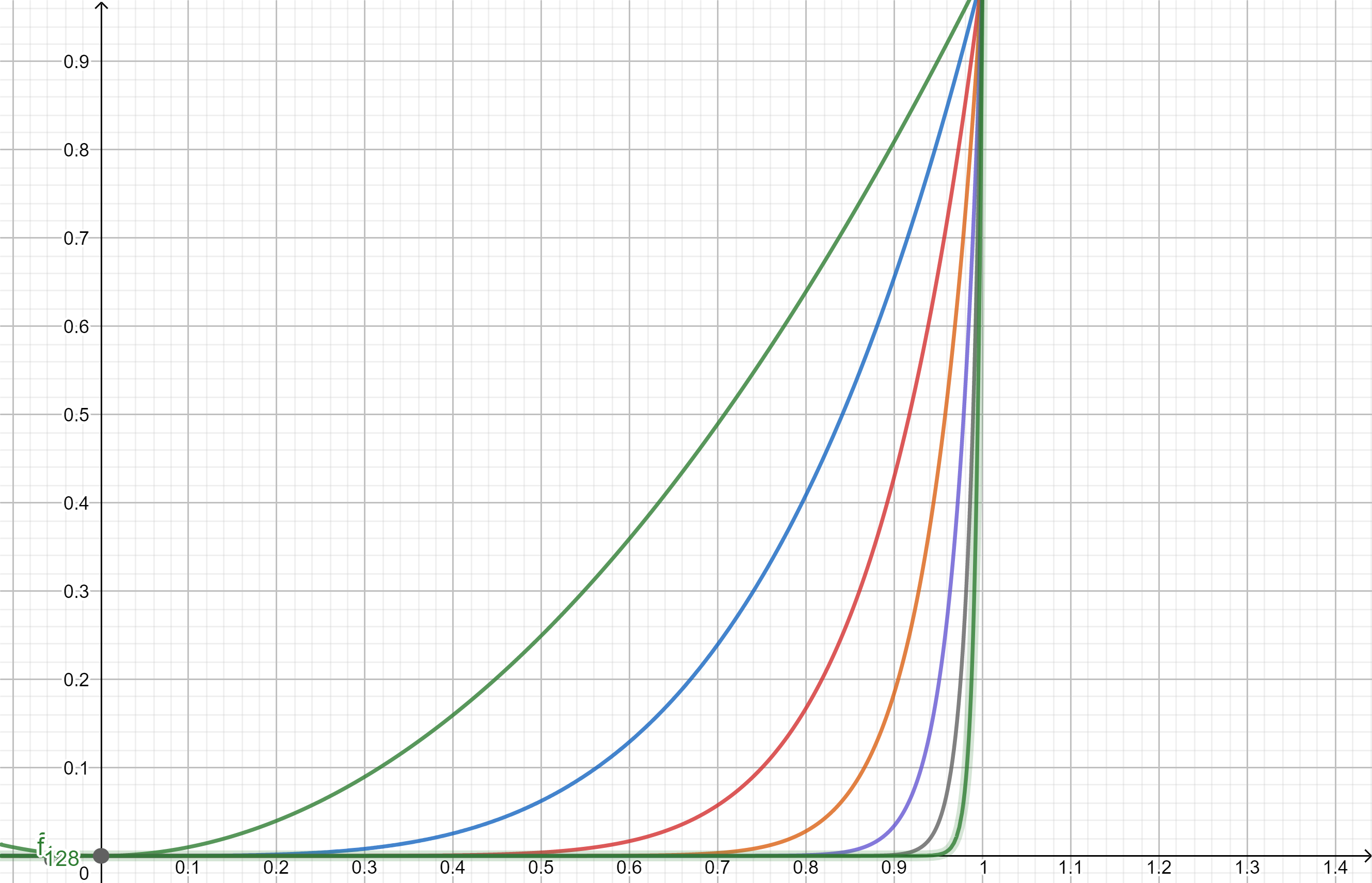

Example 1. Let \(g_n(x)=x^n\) for \(x \in [0,1]\), then \[\begin{aligned} \lim_{n \to \infty}g_n(x)=\begin{cases} 0 \text{ if }x\in[0,1),\\ 1 \text{ if }x=1. \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

Graphs of \(g_2,g_4,g_8,g_{16},g_{32},g_{64},g_{128}\)

Examples

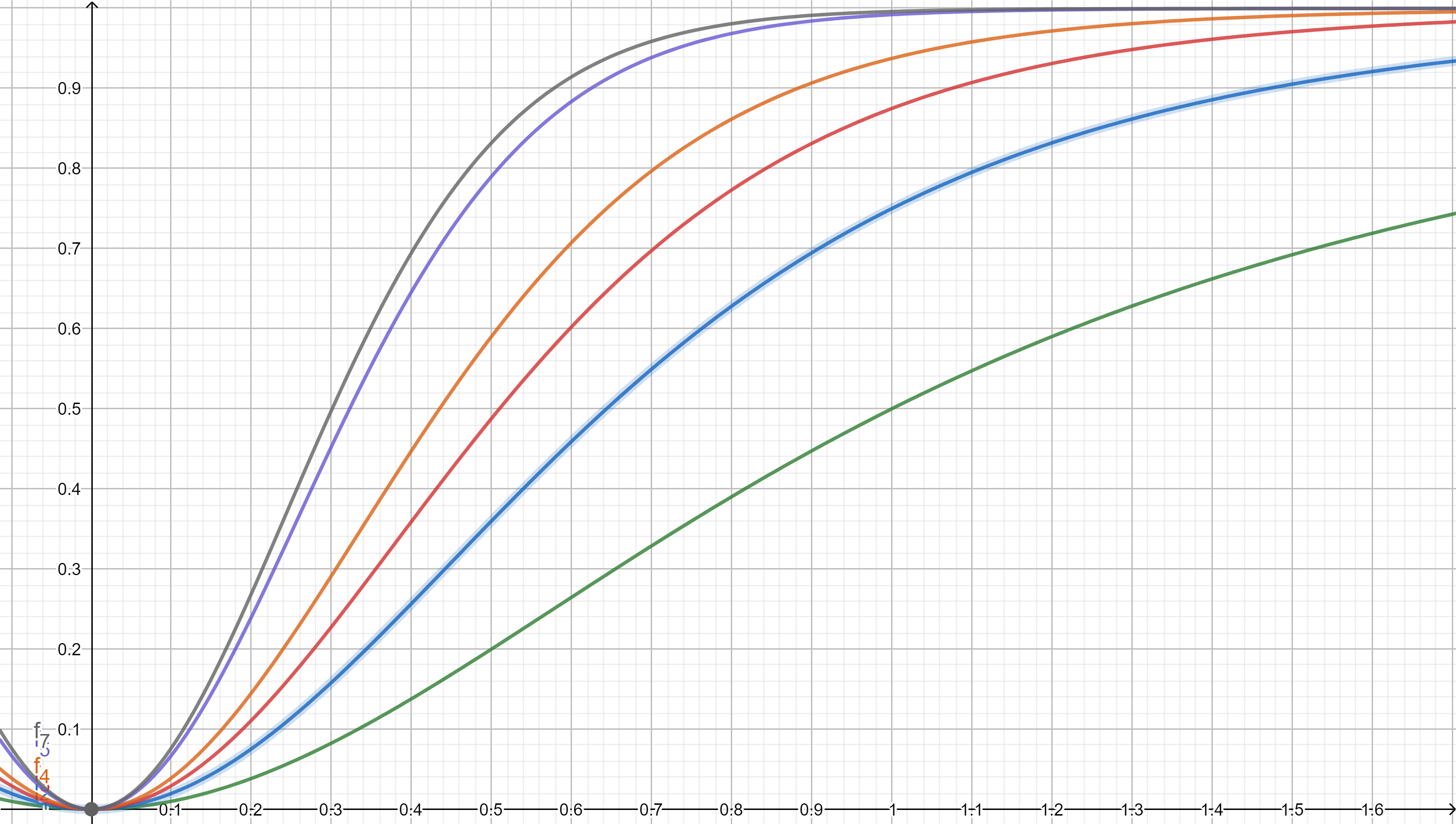

Example 2. Let \(f_n(x)=\frac{x^2}{(1+x^2)^n}\). Consider \(s_N(x)=\sum_{n=0}^Nf_n(x)\), then \[s_N(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{N \to \infty}}\ f(x),\] where \[f(x)=\begin{cases} 0 &\text{ if }x=0,\\ 1+x^2 &\text{ if }x \neq 0 \end{cases}\] since if \(x \neq 0\) one has \[\lim_{N \to \infty}s_N(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{x^2}{(1+x^2)^n}=\frac{x^2}{1-\frac{1}{1+x^2}}=1+x^2.\]

Graphs of \(s_1,s_2,s_3,s_4,s_5,s_6,s_7\)

Examples

Example 3. Let \(f_n(x)=\frac{\sin(nx)}{\sqrt{n}}\), then \(f(x)=\lim_{n \to \infty}f_n(x)=0\). Also we see that \(f'(x)=0\), but \[f_n'(x)=\sqrt{n}\cos(nx)\] does not converge to \(f'(x)\) since \[f'(0)=\sqrt{n} \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ +\infty.\]

Uniform convergence

Uniform convergence

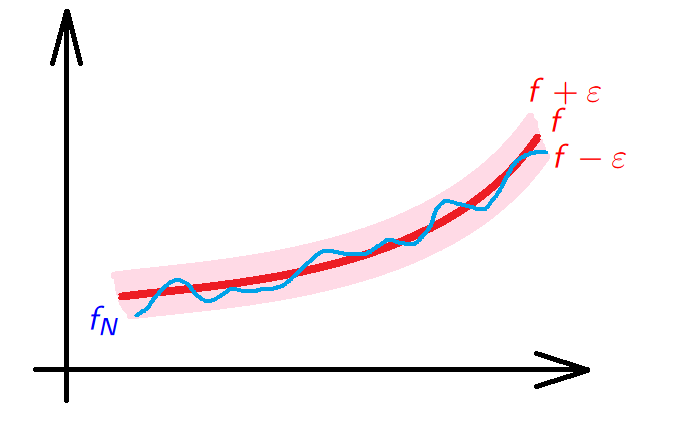

Uniform convergence. We say that a sequence of functions \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges uniformly on \(E\) to a function \(f\) is for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(n \geq N\) implies \(|f_n(x)-f(x)| \leq \varepsilon\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{N}\). We shall write \(f_n \underset{n\to \infty}{\rightrightarrows} f\) if \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges uniformly to \(f\).

Remark. Clearly every uniformly convergent sequence is pointwise convergent.

Uniform convergence - picture

Theorem

Theorem. The sequence of functions \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) defined on \(E\) converges uniformly on \(E\) iff for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there exists \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(m,n \geq N\) implies \[|f_n(x)-f_m(x)| \leq \varepsilon \quad \text{ for all }\quad x \in E.\]

Proof (\(\Longrightarrow\)). Suppose \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges uniformly on \(E\) and let \(f\) be the limit function. Then there is \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(n \geq N\) implies \[|f_n(x)-f(x)| \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2} \quad \text{ for all } \quad x \in E.\] Thus \[|f_n(x)-f_m(x)| \leq |f_n(x)-f(x)|+|f(x)-f_m(x)| \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2}+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon\] if \(n,m \geq N\) and \(x \in E\).

Proof (\(\Longleftarrow\)). Conversely, suppose that Cauchy criterion holds.

Then \((f_n(x))_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges for every \(x \in E\) to a limit, which we will call \(f(x)\).

Thus \(f_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ f\) pointwise.

We will show that the convergence is uniform.

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given and choose \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \(n,m \geq N\) implies \[|f_m(x)-f_n(x)| \leq \varepsilon \quad \text{ for all }\quad n \in E.\]

Fix \(n\) and let \(m \to \infty\). Thus \[|f_n(x)-f(x)| \leq \varepsilon\] for all \(n \geq N\) and \(x \in E\), and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Uniform convergence of a series

Theorem. \[f_n \underset{n\to \infty}{\rightrightarrows} f \quad \text{ on } \quad E \quad \iff\quad {\color{blue}M_n=\sup_{x \in E}|f_n(x)-f(x)| \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0}.\]

Proof. It is an immediate consequence of the definition.

Uniform convergence of a series. We say that the series \[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}f_n(x)\] converges uniformly on \(E\) if the sequence \[s_n(x)=\sum_{k=0}^nf_k(x)\quad \text{ converges uniformly on $E$. }\]

Theorem

Theorem. Suppose that \(f_n:E \to \mathbb{R}\) and \(|f_n(x)| \leq M_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(x \in E\). Then \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}f_n(x)\) converges uniformly on \(E\) if \[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}M_n<\infty.\]

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) and \(\sum_{k=n+1}^m M_k \leq \varepsilon\) if \(m,n \geq N\) for some \(N \in \mathbb{N}\). Then \[|s_m(x)-s_n(x)|=\left|\sum_{k=n+1}^m f_k(x)\right| \leq \sum_{k=n+1}^m M_k \leq \varepsilon\] for all \(x \in E\) and \(m,n \geq N\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Interchange limit theorem

Theorem. Suppose that \(f_n \underset{n\to \infty}{\rightrightarrows} f\) on \(E\). Let \(x\) be a limit point of \(E\) and suppose that \(\lim_{t \to x}f_n(t)=A_n.\) Then \((A_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges and \[\lim_{t \to x}f(t)=\lim_{n \to \infty}A_n.\] In other words, we may write \[\lim_{t \to x}\lim_{n \to \infty}f_n(t)=\lim_{n \to \infty}\lim_{t \to x}f_n(t).\]

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Since \(f_n \underset{n\to \infty}{\rightrightarrows} f\) there is \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(m,n \geq N\) implies \[\qquad \qquad |f_m(t)-f_n(t)| \leq \varepsilon \quad \text{ for all }\quad t \in E. \qquad \qquad {\color{purple}(*)}\]

Letting \(t \to x\) in (*) we see for all \(n,m \geq N\) that \[|A_n-A_m| \leq \varepsilon.\]

Thus \((A_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is Cauchy. Hence \(A_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ A\) for some \(A \in \mathbb{R}\). Next \[|f(t)-A| \leq {\color{red}|f(t)-f_n(t)|}+{\color{blue}|f_n(t)-A_n|}+{\color{brown}|A_n-A|}.\]

We first choose \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \({\color{red}|f(t)-f_n(t)| \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{3}}\) for all \(t \in E\), and \({\color{brown}|A_n-A| \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{3}}\).

For this \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), we choose an open set \(V\) containing \(x\) such that \[{\color{blue}|f_n(t)-A_n| \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{3}}\] if \(t \in V \cap E\) and \(t \neq x\). Hence \[|f(t)-A| \leq \varepsilon\] provided that \(t \in V \cap E\) and \(t \neq x\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Important theorems

Theorem. If \(f_n:E \to \mathbb{R}\) is continuous and \(f_n \underset{n\to \infty}{\rightrightarrows} f\) on \(E\) then \(f\) is continuous on \(E\).

Proof. It follows from the previous theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark. The converse in the theorem above is not true.

Theorem. Suppose that \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a sequence of functions differentiable on \([a,b]\) and such that \((f_n(x_0))_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges for some point \(x_0 \in [a,b]\). If \((f_n')_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges uniformly on \([a,b]\) then \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges uniformly on \([a,b]\) to a function \(f\) and \[f'(x)=\lim_{n \to \infty}f_n'(x) \quad \text{ for }\quad x \in [a,b].\]

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Choose \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \(n,m \geq N\) implies \[|f_n(x_0)-f_m(x_0)|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\quad \text{ and } \quad |f_n'(t)-f_m'(t)| < \frac{\varepsilon}{2(b-a)}\quad \text{ for }\quad t \in [a,b].\]

By the mean-value theorem applied to \(f_n-f_m\) we have \[\qquad \qquad |f_n(x)-f_m(x)-f_n(t)+f_m(t)| \leq \frac{|x-t|\varepsilon}{2(b-a)} \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2} \qquad \qquad{\color{purple}(*)}\] for any \(x,t \in [a,b]\) if \(m,n \geq N\).

The inequality \[|f_n(x)-f_m(x)| \leq |f_n(x)-f_m(x)-f_n(x_0)+f_m(x_0)|+|f_n(x_0)-f_m(x_0)|\] implies that \(|f_n(x)-f_m(x)|<\varepsilon\) for all \(m,n \geq N\) and \(x \in [a,b]\), so \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges uniformly on \([a,b]\).

Let \[{\color{blue}f(x)=\lim_{n \to \infty}f _n(x), \quad a \leq x \leq b}.\]

Fix a point \(x \in [a,b]\) and define \[\phi_n(t)=\frac{f_n(t)-f_n(x)}{t-x}, \ \ \phi(t)=\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}, \ \ t \in [a,b], \ \ t \neq x\]

Then \(\lim_{t \to x}\phi_n(t)=f_n'(x)\) for all \(n\in \mathbb N\). Inequality (*) also shows \[|\phi_n(t)-\phi_m(t)| \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2(b-a)}\quad \text{ if }\quad n,m \geq N.\]

Thus \((\phi_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges uniformly for \(x \neq t\). Since \(f_n \underset{n\to \infty}{\rightrightarrows} f\) thus \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\phi_n(t)=\phi(t)\quad \text{ for } \quad a \leq x \leq b, \quad t \neq x.\]

By the previous theorem \[\lim_{n \to \infty}f'_n(x)=\lim_{n \to \infty}\lim_{t \to x}\phi_n(t)=\lim_{t \to x}\lim_{n \to \infty}\phi_n(t)=\lim_{t \to x}\phi(t)=f'(x).\ \ \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Continuous nowhere differentiable function

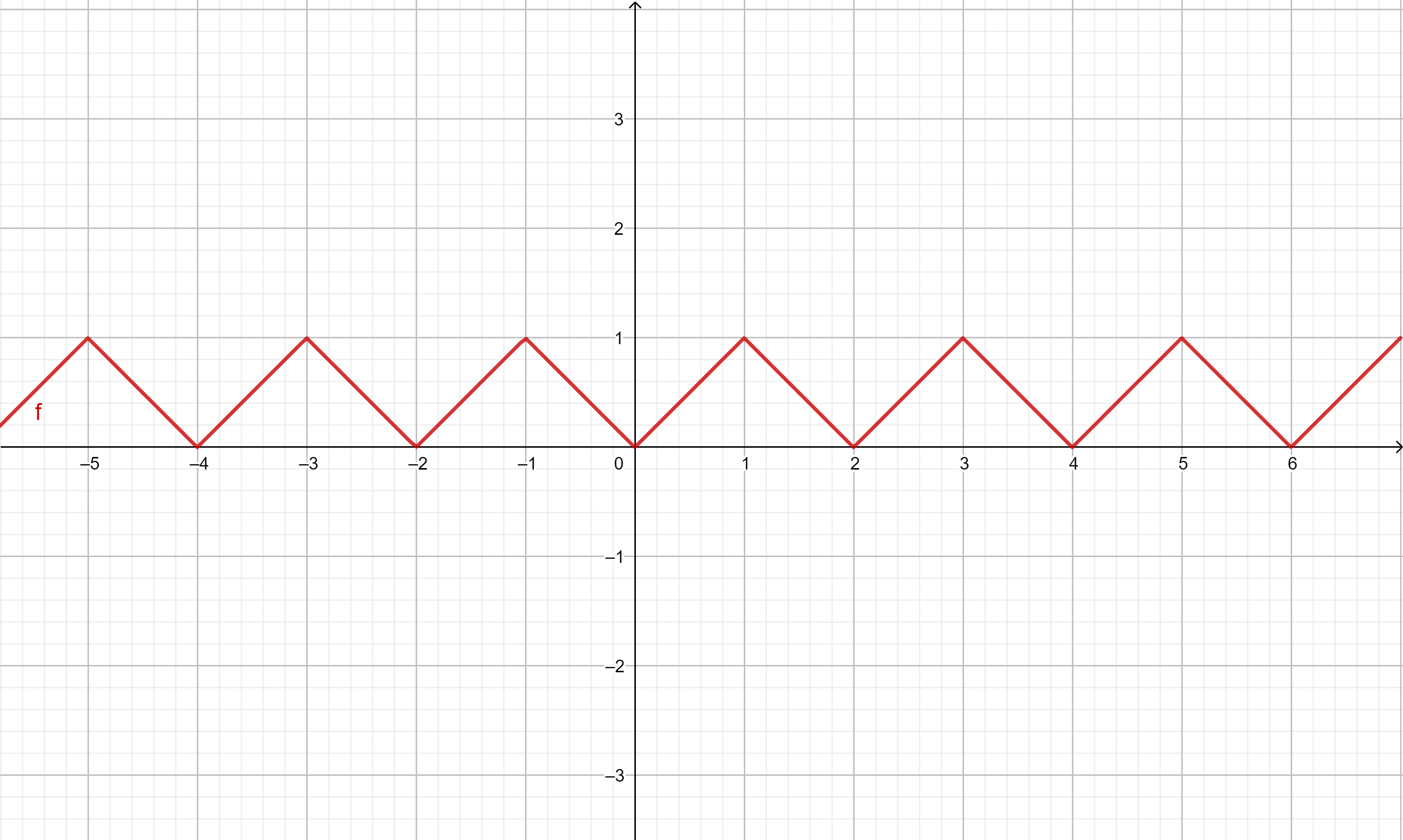

Theorem. There exists a continuous function \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) which is nowhere differentiable.

Proof. Let \(\phi(x)=|x|\) on \([-1,1]\) and extend the definition of \(\phi(x)\) to all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) by setting \[\phi(x)=\phi(x+2)\] for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\). Then \[|\phi(s)-\phi(t)| \leq |s-t| \quad \text{ for all } \quad s,t \in \mathbb{R}.\]

Graph of \(\phi\)

Define

\[{\color{blue}f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)^n\phi(4^n x)}.\]

Since \(0 \leq \phi(x) \leq 1\) then the series converges uniformly on \(\mathbb{R}\) and \(f\) is continuous.

Now fix \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(m \in \mathbb{N}\) and put \[{\color{red}\delta_m=\pm\frac{1}{2}4^{-m}},\] where the sign is chosen that no integer lies between \(4^mx\) and \(4^m(x+\delta_m)\). This can be done since \(4^m|\delta_m|=\frac{1}{2}\).

Define \[{\color{brown}\gamma_n=\frac{\phi(4^n(x+\delta_m))-\phi(4^nx)}{\delta_m}}.\]

When \(n>m\) then \(4^n\delta_m\) is an integer so that \(\gamma_n=0\).

When \(0 \leq n \leq m\), then \(|\gamma_n| \leq 4^n\). Since \(|\gamma_m|=4^m\) we conclude

\[\begin{aligned} \left|\frac{f(x+\delta_m)-f(x)}{\delta_m}\right|&=\left|\sum_{n=0}^{m}\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)^n\gamma_n\right| \\& \geq 3^m-\sum_{n=0}^{m-1}3^n =\frac{1}{2}(3^m-1) \ _{\overrightarrow{m \to \infty}}\ \infty \end{aligned}\] and \(\delta_m \ _{\overrightarrow{m \to \infty}}\ 0\) thus \(f'(x)\) does not exists.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Weierstrass theorem

Weierstrass theorem. Let \(-\infty<a<b<\infty\). Every continuous \(f:[a,b]\to\mathbb R\) can be uniformly approximated by polynomials. In other words, for every continuous \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) there is a sequence of polynomials \((p_n(f))_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) so that \[\sup_{x \in [a,b]}|p_n(f)(x)-f(x)| \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0.\]

Proof. Using a linear transformation \[[a,b] \ni t \to \frac{s-a}{s-b}\] we can assume that \([a,b]=[0,1]\). Fix a continuous \(f:[0,1] \to \mathbb{R}\), and set

\[{\color{blue}p_n(f)(t)=\sum_{k=0}^{n}{n \choose k}f\bigg(\frac{k}{n}\bigg)t^k(1-t)^{n-k}} \quad \text{ for }\quad t \in [0,1].\]

We show that \(p_n(f) \underset{n\to \infty}{\rightrightarrows} f\). Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Since \(f\) is uniformly continuous on \([0,1]\) so there is \(\delta>0\) so that \[|f(t)-f(s)|<\varepsilon \text{ if }|s-t|<\delta.\]

Note that \[\sum_{k=0}^n{n \choose k}t^k(1-t)^{n-k}=1.\]

Hence \[|f(t)-p_n(f)(t)| \leq \sum_{k=0}^n {n \choose k}\bigg|f(t)-f\bigg(\frac{k}{n}\bigg)\bigg|t^k(1-t)^{n-k}.\]

Let \({\color{brown}M=\sup_{x \in [0,1]}|f(x)|}\), and note that \[\begin{aligned} |f(t)-p_n(f)(t)| &\leq {\color{red}\varepsilon} \sum_{\substack{k=0 \\ |t-k / n|<\delta}}^{n}{n \choose k}t^k(1-t)^{n-k}\\ &+{\color{brown}2M}\sum_{\substack{k=0 \\ |t-k / n| \geq \delta}}^n{n \choose k}t^k(1-t)^{n-k} \\&\leq {\color{red}\varepsilon}+2M\delta^{-2}\sum_{k=0}^{n}{n \choose k}(t-k / n)^2 t^k(1-t)^{n-k}. \end{aligned}\]

So we have to estimate \[2M\delta^{-2}\sum_{k=0}^{n}{n \choose k}(t-k / n)^2 t^k(1-t)^{n-k}.\]

Then, using the identity

\[\sum_{k=0}^n {n \choose k}(t-k / n)^2 t^k(1-t)^{n-k}=\frac{t(1-t)}{n}\]

we obtain \[2M\delta^{-2}\sum_{k=0}^{n}{n \choose k}(t-k / n)^2 t^k(1-t)^{n-k} \leq \frac{2M\delta^{-2}}{n}\] and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

More about power series

Analytic functions

Analytic functions. Functions which can be represented as power series \[ \qquad\qquad{\color{blue}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n, \quad x \in \mathbb{R}}, \qquad\qquad {\color{purple}(*)} \] or more generally \[ \qquad\qquad{\color{blue}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_n(x-a)^n, \quad x, a \in \mathbb{R}}, \qquad\qquad {\color{purple}(**)}\] are called analytic functions.

Remark.

If (**) converges for \(|x - a|<R\) for some \(R\in (0, \infty]\), \(f\) is said to be expanded in a power series about the point \(x = a\).

As a matter of convenience, we shall often take \(a = 0\) without any loss of generality and work with (*).

Differentiability of power series

Suppose that the series \[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n\] converges for \(|x|<R\), then it converges uniformly on \([-R+\varepsilon, R-\varepsilon]\), no matter which \(\varepsilon>0\) is chosen. Moreover, the function \(f\) is continuous and differentiable in \((-R, R)\), and \[f'(x)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}nc_nx^{n-1}, \quad \text{ for } \quad |x|<R.\]

Proof.

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. For \(|x|\le R-\varepsilon\), by the root test, we have \[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}|c_nx^n|\le \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}|c_n(R-\varepsilon)^n|<\infty,\]

Thus the sequence \[f_N(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{N}c_nx^n\] converges absolutely to \(f(x)\) on \([-R+\varepsilon, R-\varepsilon]\).

Note that \((f_N)_{N\in \mathbb N}\) is a sequence of differentiable functions on \((-R, R)\) that converges to \(f(x)\) for any \(x\in (-R, R)\).

Moreover, \((f_N')_{N\in \mathbb N}\) converges uniformly on \([-R+\varepsilon, R-\varepsilon]\), since \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n\) and \(\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}nc_nx^{n-1}\) have the same intervals of convergence as \[\limsup_{n\to \infty}\sqrt[n]{n|c_n|}=\limsup_{n\to \infty}\sqrt[n]{|c_n|}.\]

Thus \[f'(x)=\lim_{N\to\infty}f_N'(x)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}nc_nx^{n-1}\] and clearly \(f\) is continuous as a differentiable function.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Power series are differentiable infinitaley many times

Under the assumption of the previous theorem \[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n, \quad \text{ for } \quad |x|<R\] has derivatives of all orders in \((-R, R)\), which are given by \[f^{(k)}(x)=\sum_{n=k}^{\infty}n(n-1)\cdot\ldots\cdot (n-k+1) c_nx^{n-k}, \quad \text{ for } \quad |x|<R.\] In particular, we have \[f^{(k)}(0)=k!c_k.\] Here \(f^{(0)}=f\) and \(f^{(k)}\) is the \(k\)-th derivative of \(f\) for \(k\in \mathbb N\).

Convergence at the endpoint

Suppose that the series \[s=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_n\] converges, and set \[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n, \quad \text{ for } \quad |x|<1.\] Then \[\lim_{x\to 1}f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_n.\]

Proof.

We will use the Abel summation formula. Let \(s_{-1}=0\) and \[s_n=\sum_{k=0}^{n}c_k \quad \text{ for } \quad n\in \mathbb N\cup\{0\}, \qquad \text{ and } \qquad s=\lim_{n\to\infty} s_n.\]

Note that \[ \sum_{n=0}^{m}c_nx^n=\sum_{n=0}^{m}(s_n-s_{n-1})x^n=(1-x)\sum_{n=0}^{m-1}s_nx^n+s_mx^m.\]

For \(|x|<1\) if we take \(m\to\infty\) we obtain \[ f(x)=(1-x)\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}s_nx^n.\]

Given \(\varepsilon>0\) we choose \(N\in \mathbb N\) such that \(n>N\) implies \(|s_n-s|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\). Since \((1-x)\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}x^n=1\) we may write \[ |f(x)-1|=\Big|(1-x)\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(s_n-s)x^n\Big|\le (1-x)\sum_{n=0}^N|s_n-s||x|^n+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\]

If \(x>1-\delta\) for a suitably chosen \(\delta>0\) we have \[\qquad\qquad (1-x)\sum_{n=0}^N|s_n-s||x|^n<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}. \qquad \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Product of converging series

Remark. If \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n\) converges absolutely, \({\color{red}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n=A}\), and \({\color{blue}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}b_n=B}\), and \[c_n=\sum_{k=0}^n a_kb_{n-k}, \quad \text{ for } \quad n=0,1,2,\ldots .\] Then \(\sum_{k=0}^\infty c_k={\color{red}A}{\color{blue}B}\).

By the previous theorem this result can be extended as follows:

If the series \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n=A\), \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}b_n=B\), and \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_n=C,\) converge and \[c_n=\sum_{k=0}^n a_kb_{n-k}, \quad \text{ for } \quad n=0,1,2,\ldots .\] Then \(AB=C\).

Proof.

For \(0\le x\le 1\) we let \[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_nx^n, \qquad g(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}b_nx^n, \qquad h(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n.\]

If \(0\le x< 1\) these series converge absolutely, thus by the previous remark we obtain \[f(x)\cdot g(x)=h(x), \quad \text{ for } \quad 0\le x<1.\]

By the previous theorem we may conclude that \[\lim_{x\to 1}f(x)=A, \qquad \lim_{x\to 1}g(x)=B, \qquad \lim_{x\to 1}h(x)=C.\]

Hence we obtain \(AB=C\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Uniqueness of the power series expansions

Suppose that the series \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_nx^n\) and \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}b_nx^n\) converge in the segment \(S=(-R, R)\). Let \[E=\Big\{x\in S: \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_nx^n=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}b_nx^n\Big\}.\] If \(E\) as a limit point in \(S\), then \(a_n=b_n\) for all \(n\in \mathbb N\cup\{0\}\), and \(E=S\).

Proof.

Put \(c_n=a_n-b_n\) and let \[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n, \quad \text{ for } \quad x\in S.\] Then \(f(x)=0\) on \(E\). We prove that \(f(x)=0\) on \(S\).

Let \(A\) be the set of all limit points of \(E\) in \(S\), and let \(B\) consist of all other points of \(S\). It is clear from the definition of “limit point” that \(B\) is open. Suppose we can prove that \(A\) is open.

Then \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint open sets. Hence they are separated. Since \(S = A \cup B\), and \(S\) is connected, one of \(A\) and \(B\) must be empty. By hypothesis, \(A\) is not empty. Hence \(B\) is empty, and \(A = S\). Since \(f\) is continuous in \(S\), \(A \subseteq E\).

Thus \(E = S\), and \(c_k=\frac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}=0\) for \(k\in \mathbb N\cup\{0\}\) which is the desired conclusion.

Now we have to prove that \(A\) is open. If \(x_0\in A\), then it is easy to show that \[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}d_n(x-x_0)^n, \quad \text{ for } \quad |x-x_0|<R-|x_0|.\]

We claim that \(d_n=0\) for all \(n\in \mathbb N\cup\{0\}\). Otherwise, let \(k\in \mathbb N\cup\{0\}\) be the smallest integer such that \(d_k\neq0\). Then \[\qquad f(x)=(x-x_0)^kg(x), \quad \text{ for } \quad |x-x_0|<R-|x_0|, \qquad {\color{purple}(*)}\] where \[g(x)=\sum_{m=0}^{\infty}d_{n+m}(x-x_0)^m.\]

Since \(g\) is continuous at \(x_0\) and \(g(x_0)=d_k\neq0\), there exists a \(\delta>0\) such that \(g(x)\neq0\) if \(|x-x_0|<\delta\).

It follows from (*) that \(f(x)\neq0\) for \(0<|x-x_0|<\delta\). But this contradicts the fact that \(x_0\in A\) is a limit point of \(E\), which ensures by continuity of \(f\) that \(f(x_0)=0\).

Thus we have proved that \(d_n=0\) for all \(n\in \mathbb N\cup\{0\}\), so \(f(x)=0\) on a neighborhood of \(x_0\in A\). This show that \(A\) is open as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$