4. Dedekind cuts, construction of $\mathbb R$ from $\mathbb Q$; Consequences of the Axiom of Completeness; Decimals, Extended Real Number System PDF

Dedekind Cuts

Definition of Dedekind cuts. A Dedekind cut is any subset \(\alpha\) of \(\mathbb{Q}\) with the following three properties:

\(\alpha \neq \varnothing\) and \(\alpha \neq \mathbb{Q}\).

If \(p \in \alpha\), \(q \in \mathbb{Q}\) and \(q<p\), then \(q \in \alpha\).

If \(p \in \alpha\) then \(p<r\) for some \(r \in \alpha\).

Remark.

The letters \(p,q,r\) will denote rational numbers and \(\alpha,\beta,\gamma\) will denote Dedekind cuts, which will be simply called cuts.

Property (iii) simply says that \(\alpha\) has no largest member.

Property (ii) implies two facts which will be freely used:

If \(p\in \alpha\) and \(q\not\in \alpha\), then \(p<q\).

If \(r\not\in \alpha\) and \(r<s\), then \(s\not\in \alpha\).

The set of real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\)

Definition of \(\mathbb R\). We set \[\mathbb{R}=\{\alpha \subset \mathbb{Q}: \alpha \text{ is a Dedekind cut}\}.\]

Order on \(\mathbb R\). Define the order on \(\mathbb{R}\) by setting \[\alpha<\beta \quad \text{ if } \quad \alpha \subset \beta.\] Here, \(\alpha\) is a proper subset of \(\beta\), i.e. \(\alpha \neq \beta\).

One has to show:

if \(\alpha<\beta\) and \(\beta<\gamma\), then \(\alpha<\gamma\),

if \(\alpha,\beta \in \mathbb{R}\), then only one of the following holds: \[\alpha<\beta, \quad \text{ or } \quad \alpha=\beta, \quad \text{ or } \quad \alpha>\beta.\]

Proof of (i) If \(\alpha<\beta\) and \(\beta<\gamma\) it is clear that a \(\alpha <\gamma\). A proper subset of a proper subset is a proper subset. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof of (ii) It is also clear that at most one of the three relations \[\alpha<\beta, \quad \text{ or } \quad \alpha=\beta, \quad \text{ or } \quad \alpha>\beta.\] can hold for any pair \(\alpha, \beta\).

To show that at least one holds, assume that the first two fail.

Then \(\alpha\) is not a subset of \(\beta\). Hence there is a \(p \in \alpha\) with \(p \notin \beta\).

If \(q \in \beta\), it follows that \(q<p\) (since \(p \notin \beta\) ), hence \(q \in \alpha\), by (i).

Thus \(\beta \subset \alpha\). Since \(\beta \neq \alpha\), we conclude that \(\beta<\alpha\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Thus \(\mathbb R\) is now an ordered set.

Least–upper–bound property

The ordered set \(\mathbb{R}\) has the least upper bound property.

Proof: To prove this, let \(\varnothing \neq A\subseteq \mathbb R\), and assume that \(\beta \in \mathbb{R}\) is an upper bound of \(A\), i.e. \(\alpha< \beta\) for every \(\alpha\in A\). Define \[\gamma=\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}\alpha.\] In other words, \(p \in \gamma\) if and only if \(p \in \alpha\) for some \(\alpha \in A\). We shall prove that \(\gamma \in \mathbb{R}\) and that \[\gamma=\sup A.\]

Proof of property (i): Since \(A\neq\varnothing\), there exists an \(\alpha_{0} \in A\). This \(\alpha_{0}\neq\varnothing\) by the property (i). This ensures that \(\gamma\neq\varnothing\), since \(\alpha_{0} \subset \gamma\). Next, \(\gamma\subset \beta\) (since \(\alpha \subset \beta\) for every \(\alpha \in A\) ), and therefore \(\gamma \neq \mathbb{Q}\). Thus \(\gamma\) satisfies property (i). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof of property (ii): Pick \(p \in \gamma\) and \(q<p\). We show that \(q \in \gamma\).

Since \(p \in \gamma\), then \(p \in \alpha_{1}\) for some \(\alpha_{1} \in A\).

Since \(q<p\), then \(q \in \alpha_{1}\), hence \(q \in \gamma\); this proves property (ii).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof of property (iii): Pick \(p \in \gamma\). We show that \(p<r\) for some \(r\in\gamma\).

Since \(p \in \gamma\), then \(p \in \alpha_{1}\) for some \(\alpha_{1} \in A\).

Choose \(r \in \alpha_{1}\) so that \(r>p\), then we see that \(r \in \gamma\) (since \(\alpha_{1} \subset \gamma\)), and therefore \(\gamma\) satisfies property (iii).

We have shown that \(\gamma\in\mathbb R\). It remain to show that \(\gamma=\sup A\).

It is clear that \(\alpha \leq \gamma\) for every \(\alpha \in A\).

If \(\delta<\gamma\), then there is an \(s \in \gamma\) such that \(s \notin \delta\). Since \(s \in \gamma\), then \(s \in \alpha\) for some \(\alpha \in A\). Now taking \(p\in \delta\) we see that \(p<s\), since \(s \notin \delta\). But \(s\in\alpha\) thus \(p\in\alpha\) by property (ii) and consequently \(\delta\subset\alpha\).

Hence, \(\delta<\alpha\), and \(\delta\) is not an upper bound of \(A\).

This gives the desired result and \(\gamma=\sup A\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Addition and zero in \(\mathbb R\)

Addition and zero in \(\mathbb R\). For \(\alpha,\beta\in \mathbb R\) we define it sum by setting \[\alpha+\beta=\{r+s: r \in \alpha, \; s \in \beta\}.\] The neutral element for addition in \(\mathbb{R}\) is defined by \(0^{*}=\{u \in \mathbb{Q}: u<0\}\).

It is easy to check that \(0^{*}\) is a cut.

Exercise: \(\mathbb R\) with \(0^*\) is an abelian group satisfying addition axioms (A):.

(A1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\), then \(x+y \in \mathbb{R}\),

(A2) \(x+y=y+x\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\),

(A3) \((x+y)+z=x+(y+z)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{R}\),

(A4) we have \(x+0^*=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\),

(A5) to every \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) corresponds an element \((-x) \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \[x+(-x)=0^*.\]

Multiplication and one in \(\mathbb{R}_+\)

Multiplication and one in \(\mathbb{R}_+\). We define the set of positive real numbers by \[\mathbb{R}_{+}=\{\alpha \in \mathbb{R}: \alpha>0^{*}\}\] and multiplication in \(\mathbb{R}_{+}\) by setting \[\alpha\beta=\{p\in \mathbb{Q}: p \leq rs \text{ for some } r\in \alpha,\; s\in \beta,\;r,s>0\}.\] The identity element for multiplication in \(\mathbb{R}_+\) is defined by \[1^*=\{q \in \mathbb{Q}:q<1\}.\]

Exercise

Exercise: \(\mathbb R\) with \(1^*\) is an abelian group satisfying multiplication axioms (M):.

(M1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}_+\), then their product \(xy \in \mathbb{R}_+\),

(M2) \(xy=yx\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}_+\),

(M3) \((xy)z=x(yz)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{R}_+\),

(M4) we have \(1^*\neq0^*\) and \(1^*\cdot x=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}_+\),

(M5) if \(0^*\neq x \in \mathbb{R}_+\) then there is an element \({x}^{-1} =\frac{1^*}{x}\in \mathbb{R}_+\) such that \[x \cdot {x}^{-1}=1^*.\]

Exercise: \(\mathbb R_+\) satisfies distributive law (D):.

(D1) \(x(y+z)=xy+xz\) holds for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{R}\).

Multiplication and one in \(\mathbb{R}\)

Multiplication in \(\mathbb{R}\). We complete the definition of multiplication by setting \(0^*\alpha=\alpha0^*=0^*\), and by setting \[\alpha\beta=\begin{cases} (-\alpha)(-\beta)\text{ if }\alpha<0^* \text{ and }\beta<0^*,\\ -((-\alpha)\beta) \text{ if }\alpha<0^* \text{ and }\beta>0^*,\\ -(\alpha(-\beta)) \text{ if }\alpha>0^* \text{ and }\beta<0^*. \end{cases}\]

Exercise. Now \(\mathbb{R}\) satisfies the multiplication (M) and the distributive law (D) axioms.

Exercise: \(\mathbb{R}\) satisfies ordered field axioms (O):.

(O1) if \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(y<z\), then \(x+y<x+z\),

(O2) if \(x>0\) and \(y>0\), then \(xy>0\).

So we have shown that \(\mathbb{R}\) is an ordered field with the least–upper–bound property.

\(\mathbb{Q}\) is subfield of \(\mathbb{R}\)

We associate with each \(r \in \mathbb{Q}\) the set \[r^*=\{p \in \mathbb{Q}: p<r\}.\] Clearly \(r^*\) is a cut and satisfies the following relations:

\(r^*+s^*=(r+s)^*\),

\(r^*s^*=(rs)^{*}\),

\(r^*<s^* \iff r<s\).

The set of all such cuts will be denoted by \[\mathbb Q^*=\{r^*: r\in\mathbb Q\}\subseteq \mathbb R.\]

There is a canonical filed isomorphism \(\Phi:\mathbb Q\to \mathbb Q^*\) given by \[\Phi(r)=r^*\quad \text{ for all } \quad r\in\mathbb Q.\] In particular, \(\mathbb{Q}\) is a subfield of \(\mathbb{R}\) via this identification.

\(\mathbb R\) is an ordered field satisfying (AoC) and contains \(\mathbb Q\)

There exists a set of real numbers \(\mathbb R\), which is an ordered field containing \(\mathbb Q\) and satisfying the axiom of completeness (AoC).

Axiom of completeness (AoC). Every \(\varnothing\neq A\subseteq\mathbb R\) that is bounded above has the least–upper–bound.

\(\mathbb R\) with \(+\) is an abelian group satisfying addition axioms (A):.

(A1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\), then \(x+y \in \mathbb{R}\),

(A2) \(x+y=y+x\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\),

(A3) \((x+y)+z=x+(y+z)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{R}\),

(A4) \(\mathbb{R}\) contains the element \(0\) such that \(x+0=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\),

(A5) to every \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) corresponds an element \((-x) \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \[x+(-x)=0.\]

\(\mathbb R\) with \(\cdot\) is an abelian group satisfying multiplication axioms (M):.

(M1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\), then their product \(xy \in \mathbb{R}\),

(M2) \(xy=yx\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\),

(M3) \((xy)z=x(yz)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{R}\),

(M4) \(\mathbb{R}\) contains the element \(1\neq0\) such that \(1\cdot x=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\),

(M5) if \(0\neq x \in \mathbb{R}\) then there is an element \({x}^{-1} =\frac{1}{x}\in \mathbb{R}\) such that \[x \cdot {x}^{-1}=1.\]

\(\mathbb R\) with \(+\) and \(\cdot\) satisfies distributive law (D):.

(D1) \(x(y+z)=xy+xz\) holds for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{R}\).

\(\mathbb R\) with \(<\) satisfies ordered field axioms (O):.

(O1) if \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(y<z\), then \(x+y<x+z\),

(O2) if \(x>0\) and \(y>0\), then \(xy>0\).

Consequences of Axiom of completeness

Nested interval property

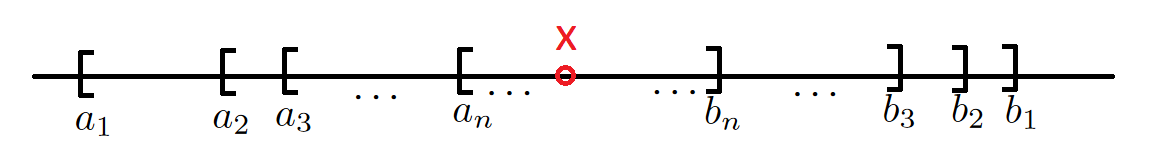

Nested interval property For each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), assume we are given a closed interval \[I_n=[a_n,b_n]=\{x \in \mathbb{R}\;:\;a_n \leq x \leq b_n\}.\]

Assume also that \(I_n \supseteq I_{n+1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). Then the resulting nested sequence of closed intervals \[I_1 \supseteq I_2 \supseteq I_3 \supseteq \ldots\] has a nonempty intersection, that is \[\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}I_n \neq \varnothing.\]

Proof: Using (AoC) we will produce \({\color{red}x} \in \mathbb{R}\) so that \({\color{red}x} \in I_n\) for every \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). Then \[\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}I_n \supset \{{\color{red}x}\} \neq \varnothing.\]

Consider the set \(A=\{a_n\;:\; n \in \mathbb{N}\}\) of all left-hand endpoints of the intervals \(I_n\). Because the intervals are nested one sees that every \(b_n\) serves as an upper bound for \(A\). Thus by the (AoC) we are allowed to write \[x=\sup A\in \mathbb R.\] The proof will be complete if we show that \(x \in I_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Since \(x\) is an upper bound for \(A\) thus \[a_n \leq x \qquad \text{ for all } \qquad n \in \mathbb{N}.\]

The fact that \(b_n\) is an upper bound for \(A\) and that \(x\) is the least upper bound implies

\[x\le b_n \qquad \text{ for all } \qquad n \in \mathbb{N}.\]

Thus \[a_n \leq x \leq b_n\] for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) hence \(x \in I_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and consequently \[x \in \bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}I_n.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Archimedian property of \(\mathbb{R}\)

Archimedian property.

Given any number \(x, z \in \mathbb{R}\) with \(z>0\) there exists \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) satisfying \[nz>x.\]

Given any real number \(y>0\) there exists an \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) satisfying \[\frac{1}{n}<y.\]

Proof. Note that (i) implies (ii) by letting \(x=\frac{1}{y}\) and \(z=1\). It suffices to prove (i). Without loss of generality we can assume that \(x>0\) and consider \[A=\{nz\;:\;n \in \mathbb{N}\}.\] Suppose for a contradiction that \(A\) is bounded, i.e. there is \(y \geq 0\) such that \(nz \leq y\) for any \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). This means that \(y\) is an upper bound for \(A\). By the (AoC): \[\alpha=\sup A \in \mathbb{R}.\]

Since \(z>0\), \(\alpha-z<\alpha\) and \(\alpha-z\) is not upper bound of \(A\). Thus we find \(m \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \[\alpha-z<mz \iff \alpha<(m+1)z.\]

This is contradiction since \(\alpha\) is the supremum of \(A\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(\mathbb{Q}\) is dense in \(\mathbb{R}\)

If \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(x<y\) then there is \(p \in \mathbb{Q}\) such that \(x<p<y\).

Proof. Since \(x<y\), by Archimedian property there is \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \[{\color{blue}n(y-x)>1}.\]

Then, we apply Archimedian property to find \(m_1,m_2 \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(m_1>nx \text{ and }m_2>-nx\). Then \(-m_2<nx<m_1.\)

Hence there is an integer \(m\) with \(-m_2 \leq m \leq m_1\) such that \[{\color{brown}m-1 \leq nx < m}.\]

We combine these inequalities to get \[\begin{aligned} {\color{brown}nx<m \leq nx+1}{\color{blue}<ny,} \qquad \text{ so } \qquad x < p=\frac{m}{n} < y. \end{aligned}\]

$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(n\)-th root of a real number

Theorem. For every real \(x>0\) and \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) there is a unique real number \(y>0\) so that \[y^n=x.\] The number \(y>0\) is called the \(n\)-th root of \(x\) and we will write \(y=\sqrt[n]{x}\).

Proof: Uniqueness. The fact that there exists at most one such \(y\) is clear, since \(0<y_1<y_2\) implies \(y_1^n<y_2^n\).

Identity \(b^n-a^n\). In the proof (in the existence part), we will use the following identity \[b^n-a^n=(b-a)(b^{n-1}+b^{n-2}a+\ldots + a^{n-2}b+a^{n-1}),\] which holds for all \(a,b \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Proof: Existence. Let \[E=\{t>0\;:\; t^n<x\}.\]

If \(t=\frac{x}{x+1}\), then \(0 \leq t<1\) hence \[t^n \leq t<x\] thus \(t \in E\) and \(E \neq \varnothing\).

If \(t>x+1\), then \(t^n>t>x\), so that \(t \not \in E\). Thus \(1+x\) is an upper bound of \(E\).

By the (AoC) we may write \(y=\sup E \in \mathbb{R}\). We will show that \[y^n=x.\]

It suffices to show that \(y^n<x\) and \(y^n>x\) cannot hold.

The identity \[b^n-a^n=(b-a)(b^{n-1}+b^{n-2}a+\ldots+ a^{n-2}b+a^{n-1})\] gives \[b^n-a^n<(b-a)nb^{n-1}\] if \(0<a<b\).

Assume \(y^n<x\). Choose \(0<h<1\) so that \[h<\frac{x-y^n}{n(y+1)^{n-1}}.\]

Put \(a=y\), \(b=y+h\). Then \[\begin{aligned} (y+h)^n-y^n<hn(y+h)^{n-1}<hn(y+1)^{n-1}<x-y^n. \end{aligned}\]

Thus \((y+h)^n<x\) and \(y+h \in E\). Since \(y+h>y\) this contradicts the fact that \(y\) is an upper bound of \(E\).

Assume that \(y^n>x\) and set \[k=\frac{y^n-x}{ny^{n-1}}.\]

Then \(0<k<y\). If \(t \geq y-k\) we conclude \[\begin{aligned} y^n-t^n \leq y^n-(y-k)^n<kny^{n-1}=y^n-x. \end{aligned}\]

Thus \(t^n>x\) and \(t \not\in E\). It follows that \(y-k\) is an upper bound of \(E\).

But \[y-k<y,\] which contradicts the fact that \(y\) is the least upper bound of \(E\).Hence \[y^n=x.\]

Corollary

Corollary. If \(a,b>0\) are real numbers and \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), then \[(ab)^{1/n}=a^{1/n}b^{1/n}\]

It is a consequence of the uniqueness property in the previous theorem.

Exercise: \(x^y\) for \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\)

Fix \(b>1\).

If \(m,n,p,q \in \mathbb{Z}\), \(n,q>0\) and \(r=\frac{m}{n}=\frac{p}{q}\), then \[(b^m)^{\frac{1}{n}}=(b^p)^{\frac{1}{q}}.\]

Hence, it makes sense to define \(b^r=(b^{m})^{\frac{1}{n}}\).

If \(r,s \in \mathbb{Q}\), then \[b^{r+s}=b^rb^s.\]

If \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) define \[B(x)=\{b^t \;:\;t \in \mathbb{Q}, \, t \leq x\}.\]

Then \(b^r=\sup B(r)\) when \(r \in \mathbb{Q}\). Hence, it makes sense to define \[b^x=\sup B(x)\] for every \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Decimals

Decimals 1/2

Let \(x>0\) be real. Let \(n_0\) be the largest integer such that \(n_0 \leq x\).

Remark. Note that the existence of \(n_0\) follows from the Archimedian property. Why?

Then, we define \(n_1\) to be the largest integer such that \[n_0+\frac{n_1}{10} \leq x.\]

then, having \(n_0,n_1\), we define \(n_2\) to be the largest integer such that \[n_0+\frac{n_1}{10}+\frac{n_2}{100} \leq x.\]

We continue this procedure...

Decimals 2/2

Having chosen \[n_0,n_1,\ldots,n_{k-1}\] let \(n_k\) be the largest integer such that \[n_0+\frac{n_1}{10}+\frac{n_2}{10^2}+\ldots+\frac{n_k}{10^k} \leq x.\]

Let \[E=\{n_0+\frac{n_1}{10}+\frac{n_2}{10^2}+\ldots+\frac{n_k}{10^k}\;:\; k \in \mathbb{N}_0\}.\]

Then one can show that \(x=\sup E\).

Decimal system - example

Example. Write down \(0,25\) in the form \(\frac{n}{m}\).

Solution. We write \[0,25=\frac{2}{10}+\frac{5}{100}=\frac{20}{100}+\frac{5}{100}=\frac{25}{100}=\frac{1}{4}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Write down \(x=0,101010101\ldots\) in the form \(\frac{n}{m}\).

Solution. Note that \[10x=10,10101010\ldots,\] hence \[10x=10+x\]

\[9x=10 \iff x=\frac{10}{9}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The extended real numbers system

The extended real number system

The extended real number system. The extended real number system consists of real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\) and two symbols \(+\infty\) and \(-\infty\).

We preserve the original order in \(\mathbb{R}\) and define \[-\infty<x<+\infty\] for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Example. If \(E \subseteq \mathbb{R}\), \(E \neq \varnothing\) but not bounded then \[\sup E=+\infty.\]

Properties of the extended real number system

Properties. If \(x\in \mathbb{R}\), then

\(x+\infty=\infty\), \(x-\infty=-\infty\), \(\frac{x}{+\infty}=\frac{x}{-\infty}=0\),

if \(x>0\), then \(x(+\infty)=+\infty\), \(x(-\infty)=-\infty\),

if \(x<0\), then \(x(+\infty)=-\infty\), \(x(-\infty)=+\infty\).