11. Functions and their properties; Cartesian products and Axion of Choice PDF

Functions

Relations

Relations. A relation from \(X\) to \(Y\) is a subset \(R\) of \(X \times Y\), i.e. \(R\subseteq X \times Y\).

If \(X=Y\) we speak about relations on \(X\).

If \(R\) is a relation from \(X\) to \(Y\) we shall sometimes write \(xRy\) to mean that \((x,y) \in R \subseteq X \times Y\).

Functions

Functions. A function \(f:X \to Y\) is a relation from \(X\) to \(Y\) with the property that for every \(x \in X\) there is a unique element \(y \in Y\) such that \(xRy\) in which case we write \[y=f(x).\]

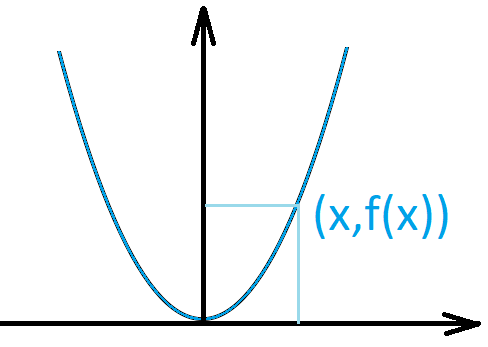

Example 1. \(X=\mathbb{R}\), \(f(x)=x^2\).

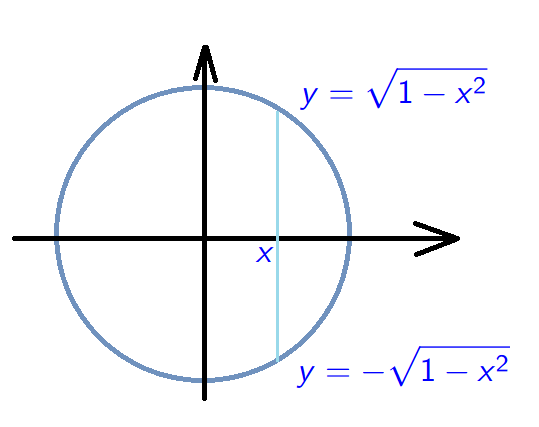

A relation which is not a function

Example 2. \[D=\{(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;x^2+y^2=1\}.\] This is not a function!

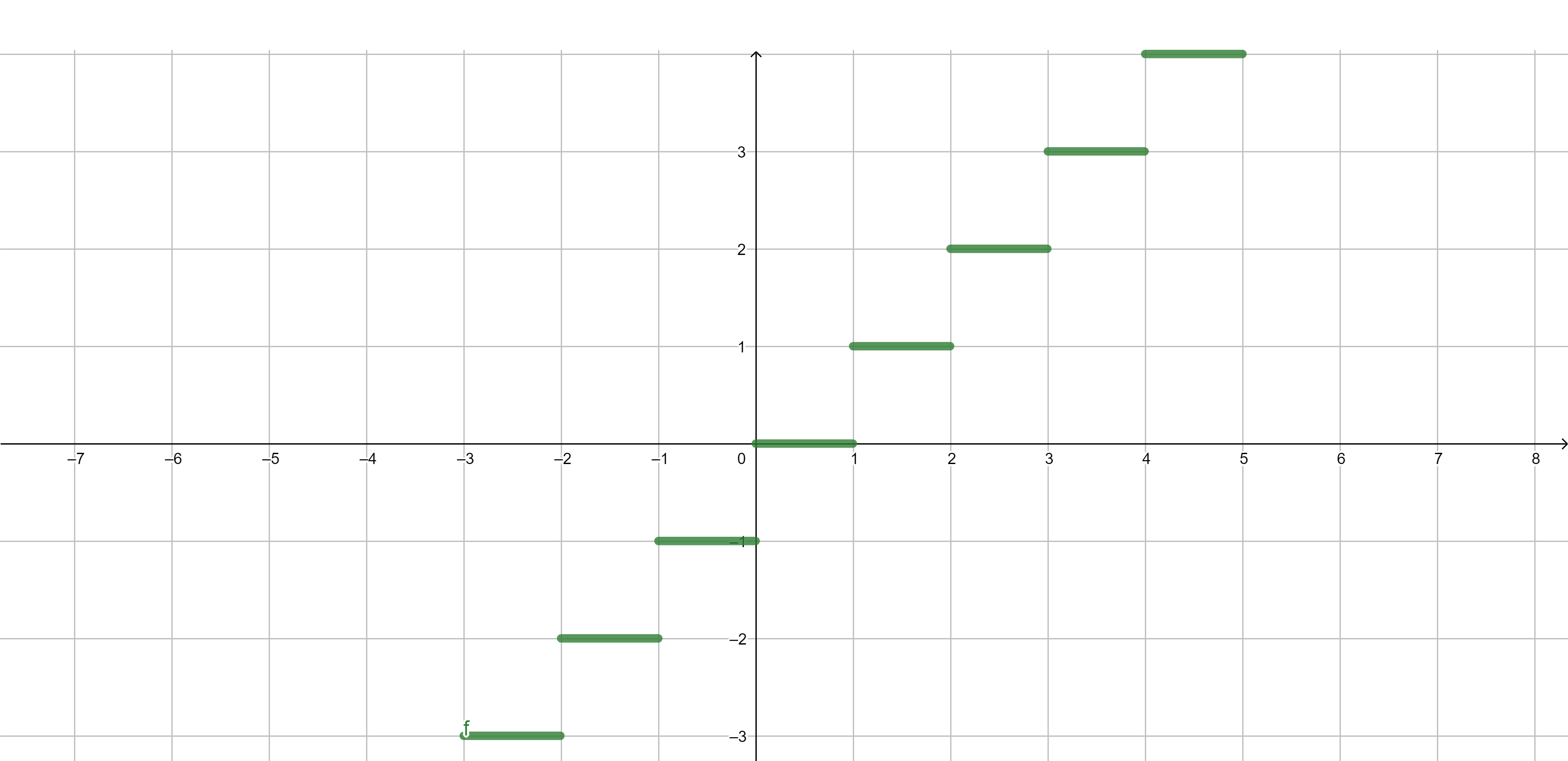

Examples of functions - integer part

Integer part \[\lfloor x\rfloor=\max\{n \in \mathbb{Z}:n \leq x\}.\]

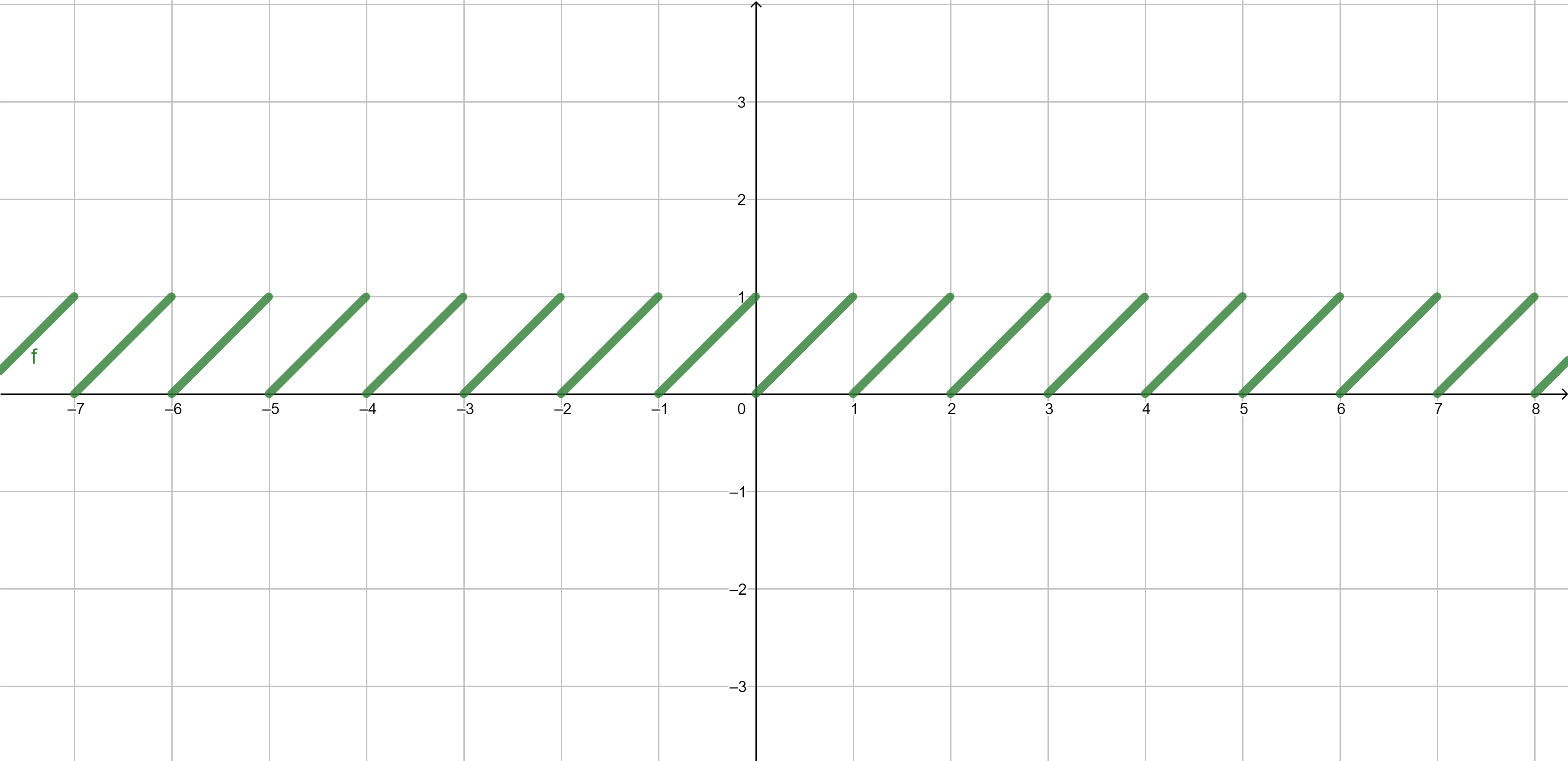

Examples of functions - fractional part

Fractional part \[\{x\}=x-\lfloor x\rfloor.\]

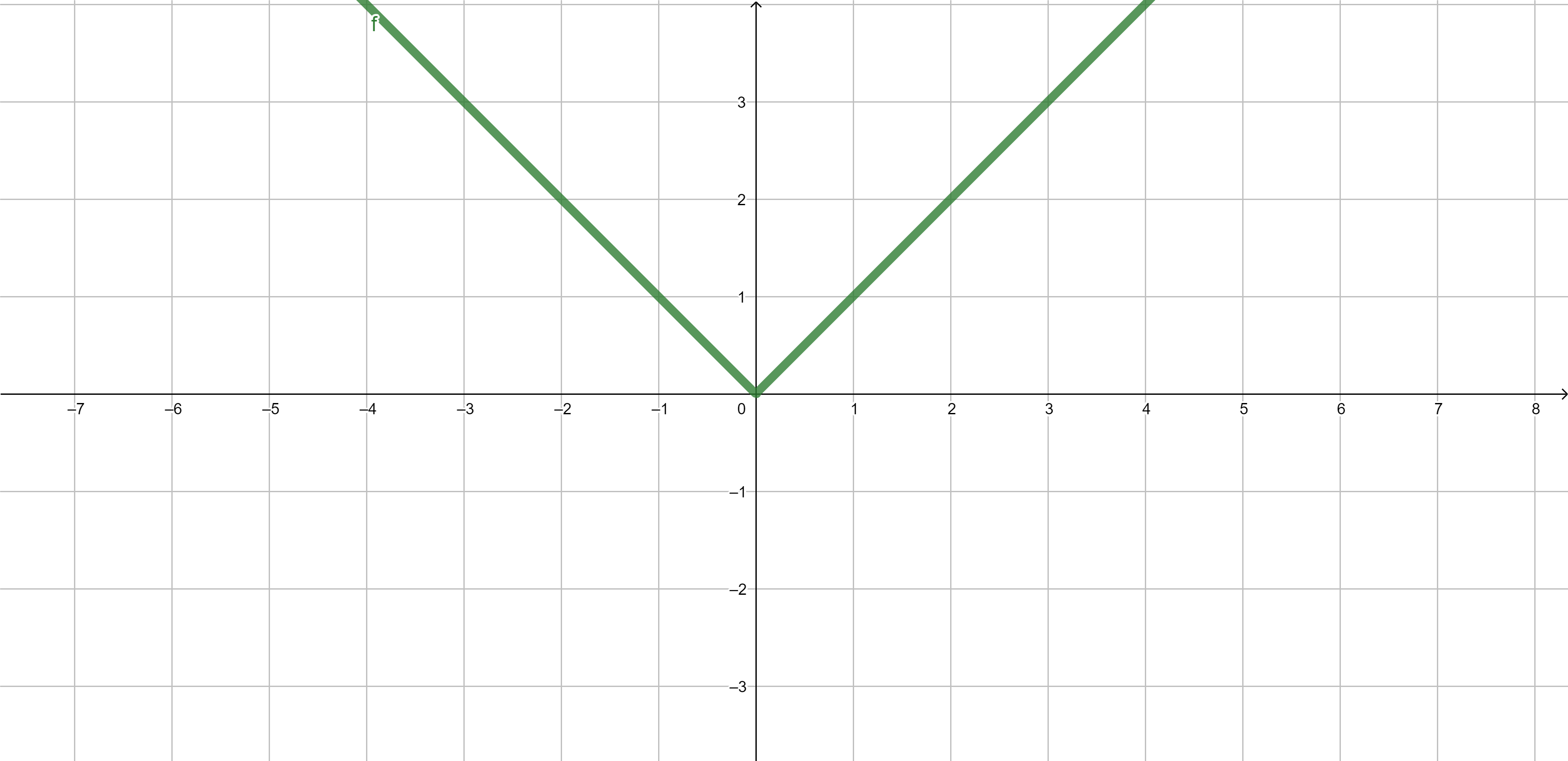

Examples of functions - absolute value

Absolute value \[|x|=\begin{cases} x & \text{ if }x\geq 0,\\ -x & \text{ if }x<0. \end{cases}.\]

Properties of functions

Composition of functions

Composition of functions. If \(f:X \to Y\) and \(g:Y \to Z\) are functions we define their composition \(g \circ f:X \to Z\) by setting \[g \circ f(x)=g(f(x)) \quad \text{ for } \quad x\in X.\]

Example. If \(f(x)=x^2-2\) and \(g(x)=|x|\), then \(g \circ f(x)=|x^2-2|\).

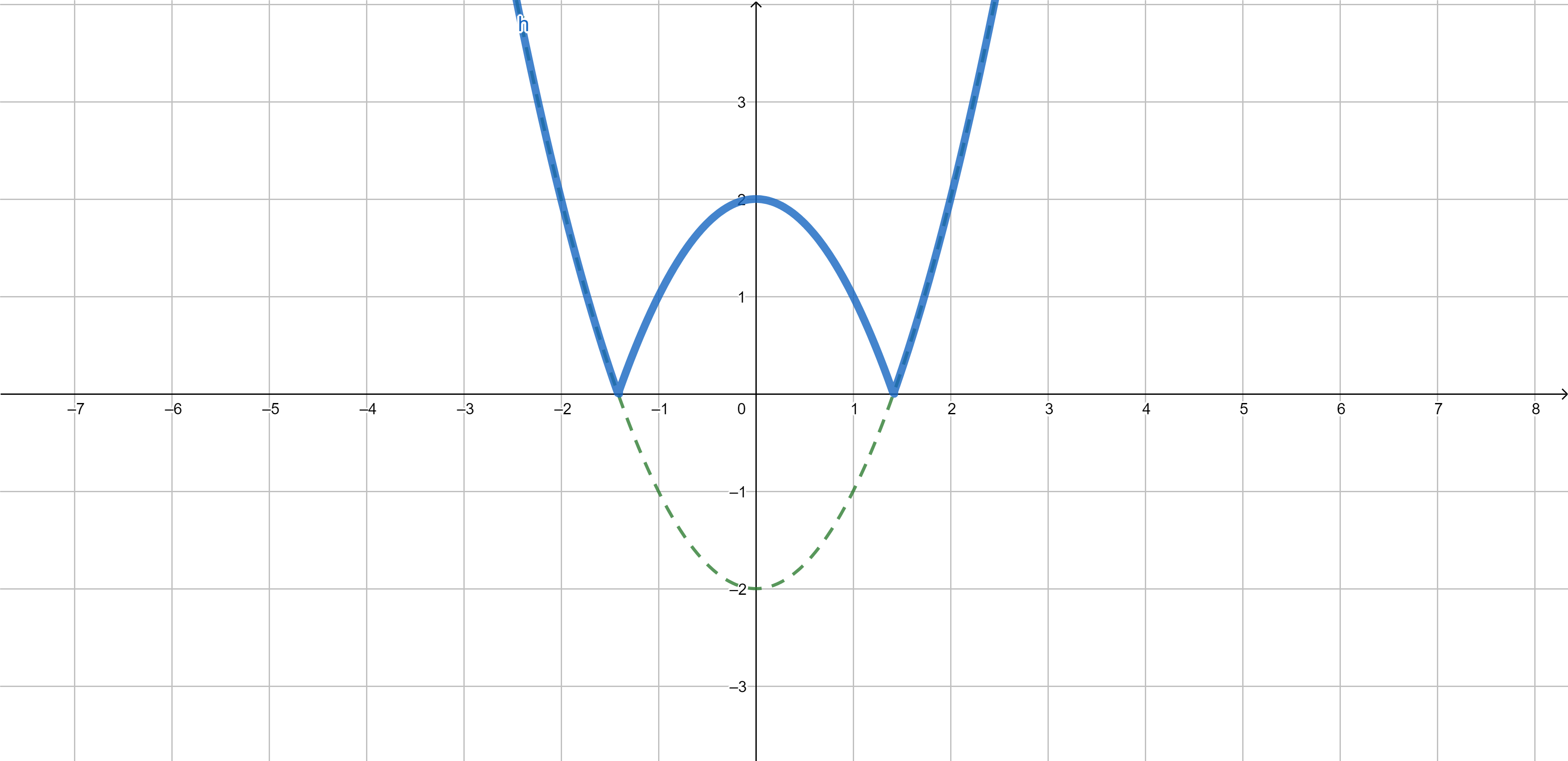

Composition of the functions - example

\[{\color{olive}f(x)=x^2-2}, \qquad {\color{red}g(x)=|x|,}\] \[{\color{blue}g \circ f(x)=|x^2-2|}\]

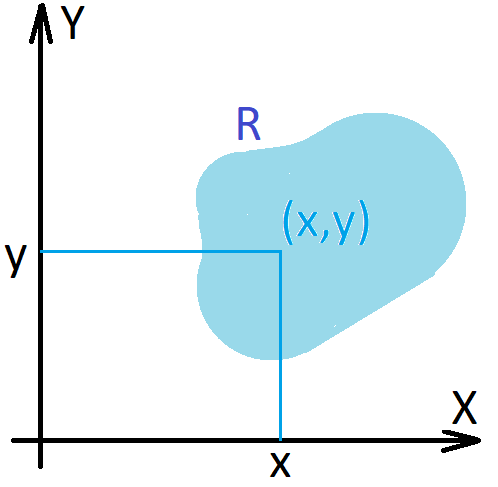

Image and inverse image

Image. If \(D \subseteq X\), we define the image of \(D\) under the function \(f:X \to Y\) by \[f[D]=\{f(x)\;:\;x \in D\}.\]

Inverse image. If \(E \subseteq Y\), we define the inverse image of \(E\) under the function \(f:X \to Y\) by \[f^{-1}[E]=\{x \in X\;:\;f(x) \in E\}.\]

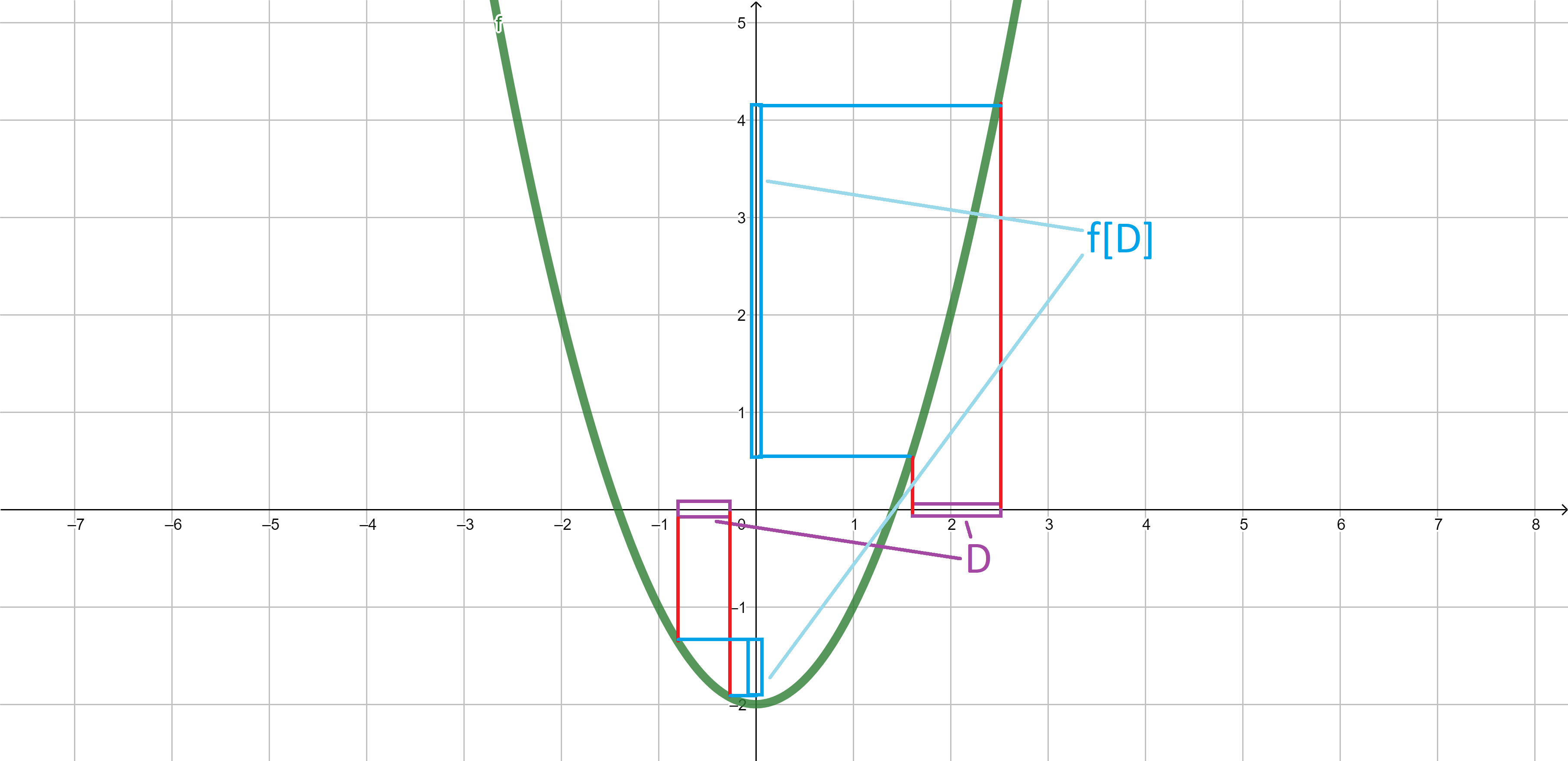

Image - example

\[{\color{blue}f[D]}=\{f(x)\;:\;x \in {\color{purple}D}\}.\]

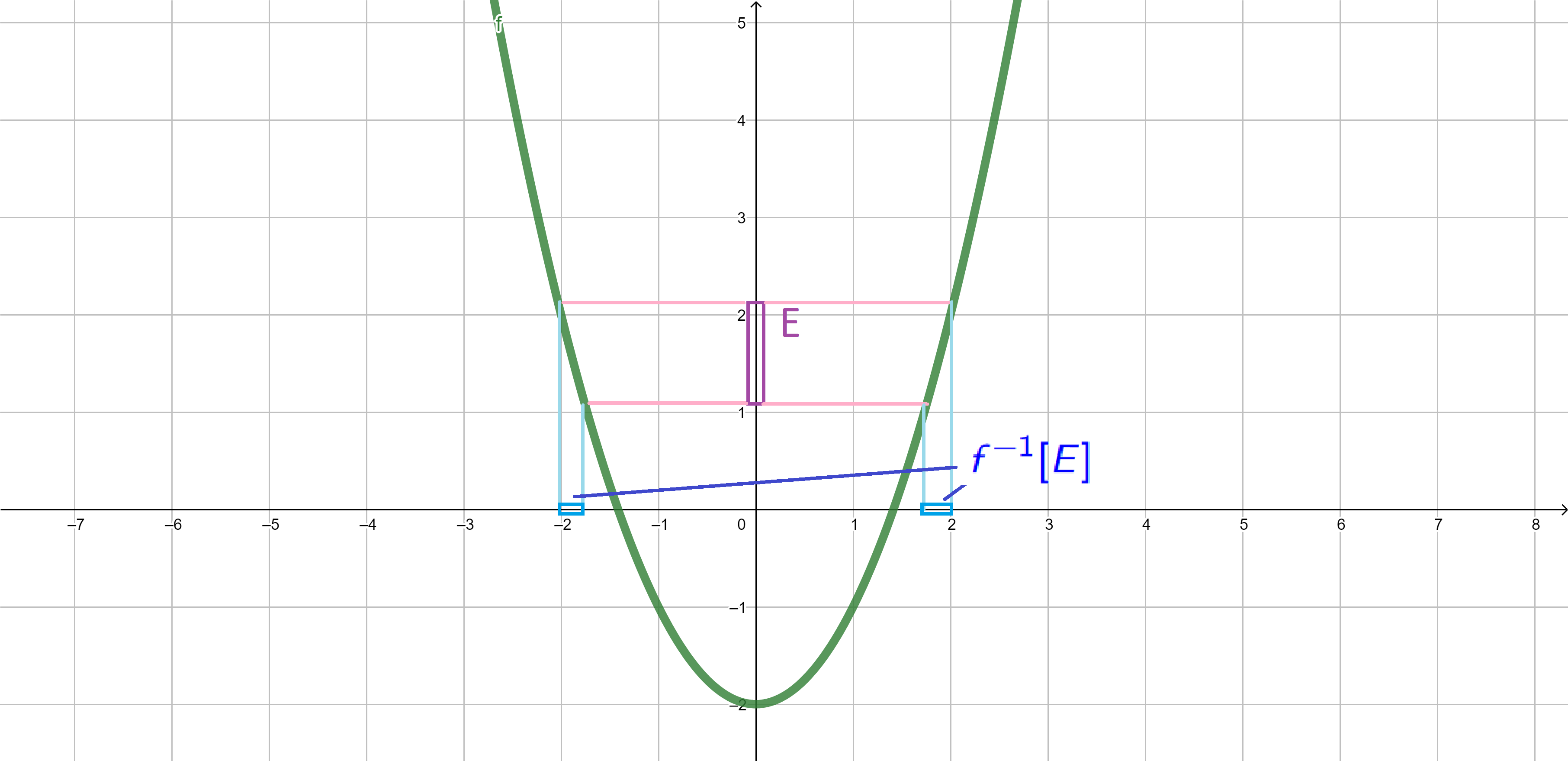

Inverse image - example

\[{\color{blue}f^{-1}[E]}=\{x \in X\;:\;f(x) \in {\color{purple}E}\}.\]

Inverse image - properties

For every function \(f:X\to Y\) one has

\[f^{-1}\left[\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}\right]=\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}f^{-1}[E_{\alpha}],\]

\[f^{-1}\left[\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}\right]=\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}f^{-1}[E_{\alpha}],\]

\[f^{-1}[E^{c}]=(f^{-1}[E])^{c}.\]

Image - properties

For every function \(f:X\to Y\) one has

\[f\left[\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}\right]=\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}f[E_{\alpha}].\]

Exercise. Corresponding formulas for intersection and complements may not be true.

Domain and range

Domain. If \(f: X \to Y\) is a function, \(X\) is called the domain of \(f\) and denoted by \[{\rm dom}(f)=X.\]

Range. If \(f: X \to Y\) is a function, \(f[X]\) is called the range of \(f\) denoted by \[{\rm rgn}(f)=f[X].\]

Example. If \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) and \(f(x)=x^2\), then \[{\rm dom}(f)=\mathbb{R} \qquad \text{ and } \qquad {\rm rgn}(f)=[0,\infty).\]

Injective functions, 1/2

Injective functions. The function \(f\) is said to be injective if \(f(x_1)=f(x_2)\) implies \(x_1=x_2\).

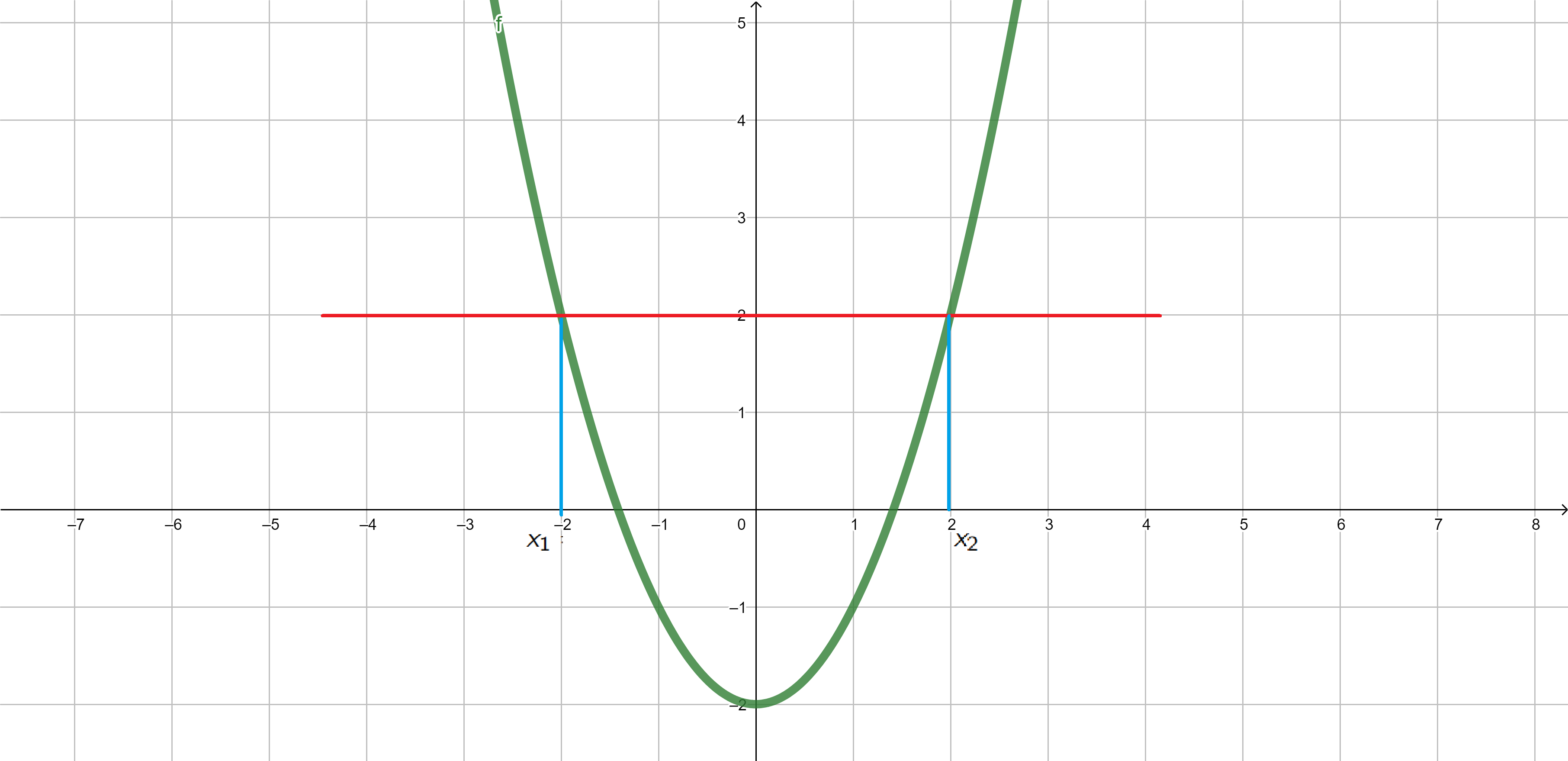

Example 1. \(f(x)=x^2-2\) is not injective since for \(x_1=-2\) and \(x_2=2\) we have \[f(x_1)=f(-2)=(-2)^2-2=2,\]

\[f(x_2)=f(2)=2^2-2=2.\]

Injective functions - example 1/2

\(f(x)=x^2-2\)

Injective functions, 2/2

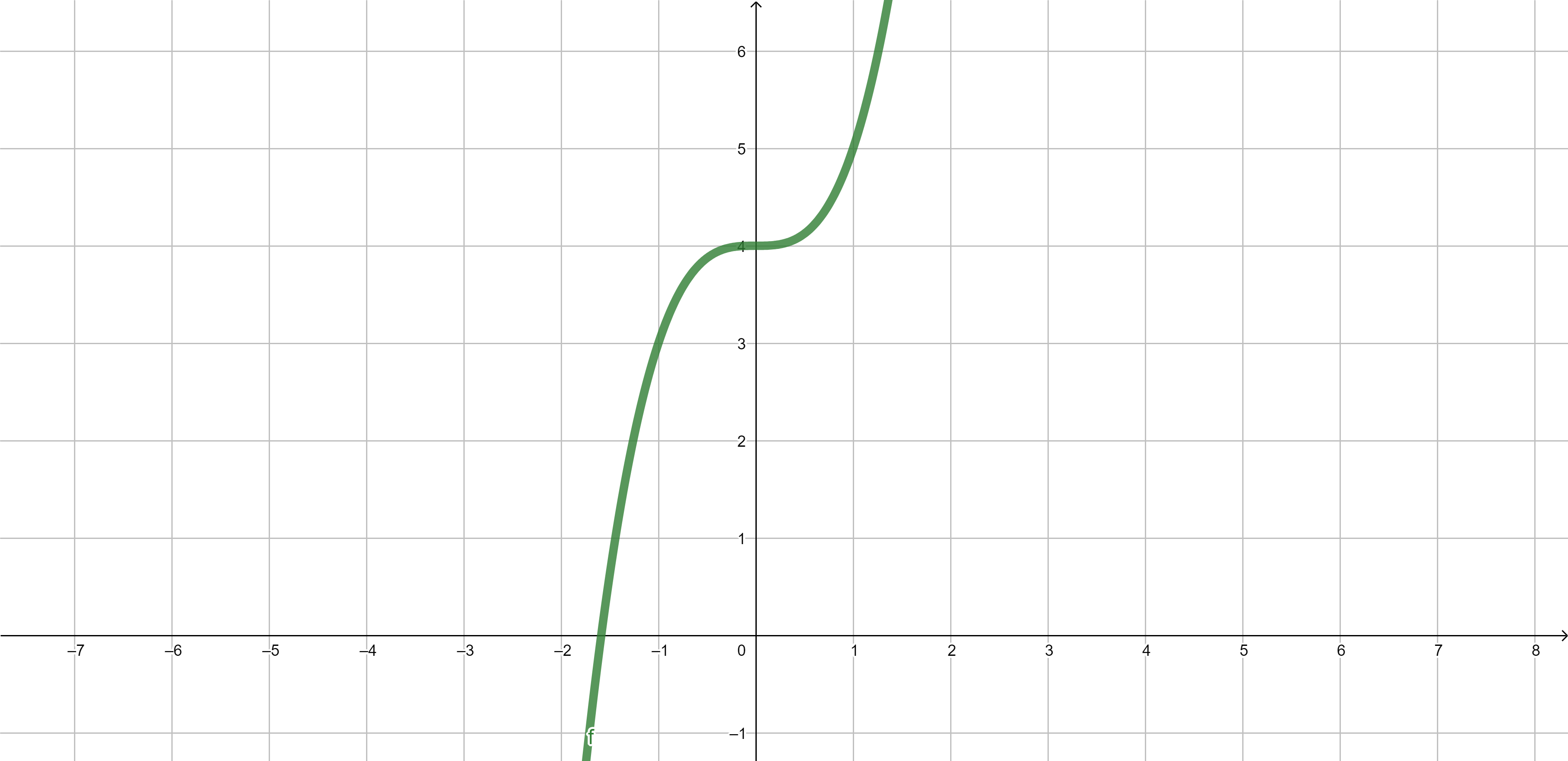

Example 2. \(f(x)=x^3+4\) is injective.

Proof: Indeed, suppose that \(f(x_1)=f(x_2)\), then

\[\begin{aligned} f(x_1)&=f(x_2) \iff\\ x_1^3+4&=x_2^3+4\iff \\ x_1^3&=x_2^3 \iff x_1=x_2. \end{aligned}\]

$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Injective functions - example 2/2

\(f(x)=x^3+4\)

Surjective functions

Surjective functions. \(f:X \to Y\) is said to be surjective if \(f[X]=Y\).

Example 1. \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x)=x^3-5\) is surjective.

Example 2. \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x)=x^2-2\) is not surjective since \[f[\mathbb{R}]=[-2,+\infty) \neq \mathbb{R}.\]

Example 3. Every mapping \(f:X \to Y\) is surjective if \(Y=f[X]\).

Bijective functions

Bijective functions. \(f:X \to Y\) is bijective if it is both injective and surjective.

Example 1. \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x)=ax+b\) is bijective is \(a \neq 0\).

Example 2. \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x)=x^3+5\) is bijective.

Example 3. \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x)=x^2+1\) is not bijective since it is not injective.

Inverse functions

Inverse functions. If \(f:X \to Y\) is bijective it has an inverse \(f^{-1}:Y \to X\) such that \[f^{-1} \circ f \quad \text{ and }\quad f \circ f^{-1}\] are both identity functions, i.e. \[f^{-1} \circ f(x)=x\quad \text{ and }\quad f \circ f^{-1}(y)=y\quad \text{ for all } \quad x \in X, y \in Y.\]

Example 1. If \(a \neq 0\), then \(f(x)=ax+b\) has an inverse given by \[f^{-1}(x)=\frac{x-b}{a}.\]

Restriction of the function

Restriction. If \(A \subseteq X\) we denote \(f_{|A}\) the restriction of \(f:X \to Y\) to \(A\): \[f_{|A}:A \to Y, \qquad f_{|A}(x)=f(x)\qquad \text{ for all } \qquad x \in A.\]

Example 1. Let \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) be defined by \(f(x)=x^2\). Let \(A=[0,+\infty)\) and let \(g(x)=f_{|A}\). Then \(f\) is not injective, but \(g\) is injective.

Axiom of Choice

Set of maps

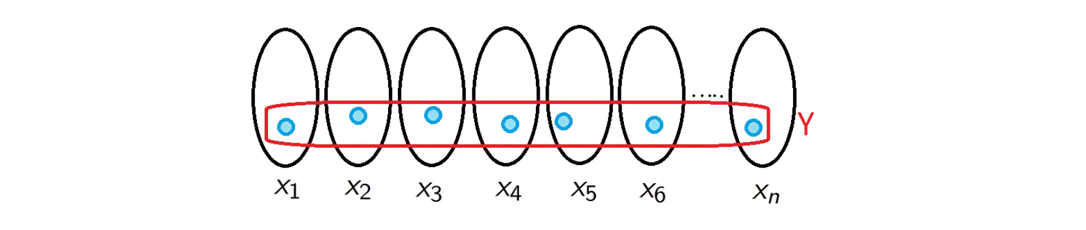

Cartesian product. If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is an indexed family of sets, their Cartesian product \[\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\] is the set of all maps \(f:A \to \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) so that \(f(\alpha)\in X_{\alpha}\) for all \(\alpha \in A\).

Projection map. If \(X=\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) and \(\alpha \in A\) we define \(\alpha\)-th projection or coordinate map \(\pi_{\alpha}:X \to X_{\alpha}\) by \(\pi_{\alpha}(f)=f(\alpha)\).

We will also write \(x=(x_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A} \in X=\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) instead of \(f\), and \(x_{\alpha}\) instead of \(f(\alpha)\).

Set of maps - examples 1/2

Example 1. If \(A=\{1,2,\ldots,n\}\), then \[\begin{aligned} X&=\prod_{j=1}^n X_j=X_1 \times X_2 \times \ldots \times X_n\\&=\{(x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_n)\;:\; x_j \in X_j \text{ for all }j=1,2,\ldots,n\}. \end{aligned}\]

Example 2. If \(A=\mathbb{N}\), then \[\begin{aligned} X&=\prod_{j=1}^\infty X_j=X_1 \times X_2 \times \ldots=\{(x_1,x_2,\ldots)\;:\; x_j \in X_j \text{ for all }j=1,2,\ldots\}. \end{aligned}\]

Set of maps - examples 2/2

Example 3. If the sets \(X_{\alpha}\) are all equal to some fixed set \(Y\), we denote \[X=\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}=Y^A.\]

\(Y^{A}\)-the set of all mappings from \(A\) to \(Y\).

Example 4. \(\mathbb{Z}^{\mathbb{N}}\) - the set of all

sequences of integers.

\(\mathbb{R}^{\mathbb{N}}\) - the set

of all sequences of real numbers.

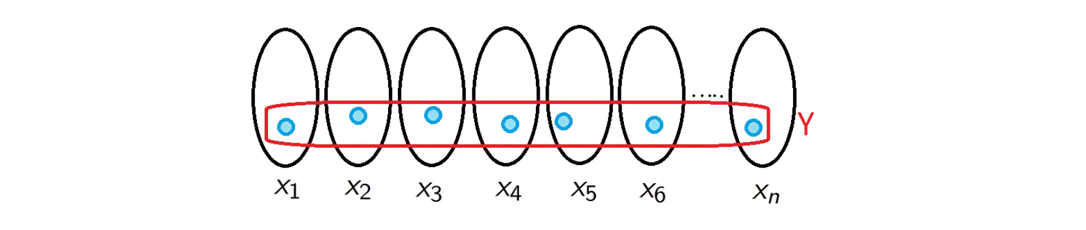

The axiom of choice

The axiom of choice. If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a nonempty collection of nonempty sets, then \[\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing.\]

Corollary. If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a disjoint collection of nonempty sets, then there is a set \(Y \subseteq \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) (called the selector of \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\)) such that \(Y \cap X_{\alpha}\) contains precisely one element for each \(\alpha \in A\).

Take \(f \in \prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing\). Define \[Y=f[A],\] then

\[Y \cap X_{\alpha}=\{f(\alpha)\},\] since \(f(\alpha) \in X_{\alpha}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark. In fact, this corollary is equivalent to the axiom of choice. Why?