16. Compact sets, Perfect Sets, Connected Sets; and Cantor set PDF

Compact sets in Euclidean spaces

Compactness in Euclidean spaces

Theorem. Every closed and bounded set of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) is complete.

Proof. We deduce compactness by showing completeness and total boundedness.

Since every closed subset of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) is complete is suffices to show that bounded subsets of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) are totally bounded.

Since every bounded set is contained in some cube \(Q=[-R,R]^n\) it is enough to show that \(Q\) is totally bounded.

Given \(\varepsilon>0\) pick the integer \(k>\frac{R\sqrt{n}}{\varepsilon}\) and express \(Q\) as the union of \(n^n\) congruent subcubes by dividing the interval \([-R,R]\) into \(k\) equal pieces.

The side length of these subcubes is \(\frac{2R}{k}\) and hence the diameter is \(\sqrt{n}\left(\frac{2R}{k}\right)<2\varepsilon\), so they are contained in the balls of radius \(\varepsilon\) about their centers. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

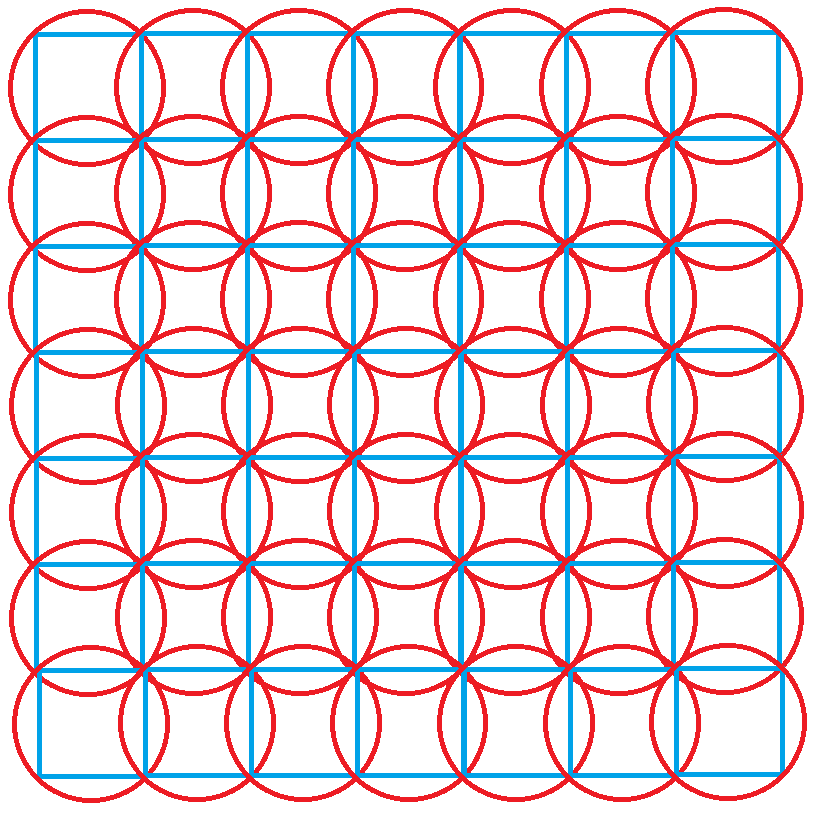

\(Q=[-R,R]^n\) is totally bounded

Example

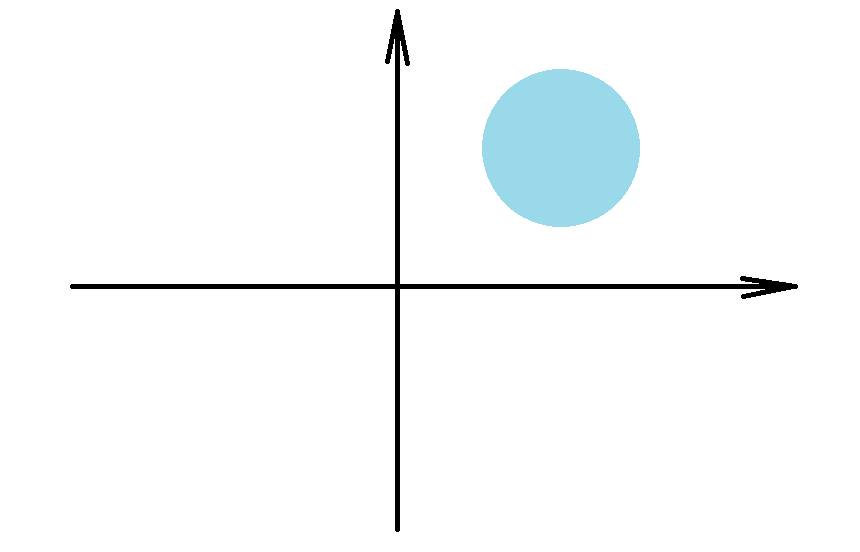

Example. Determine if the set \[X=\{(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;(x-1)^2+(y-1)^2 < 1\}\] is compact or not in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with Euclidean metric.

Solution. Note that \((2,0)\) is an accumulation point of \(X\), but \((2,0) \not\in X\). Therefore, \(X\) is not closed, so it is not compact.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

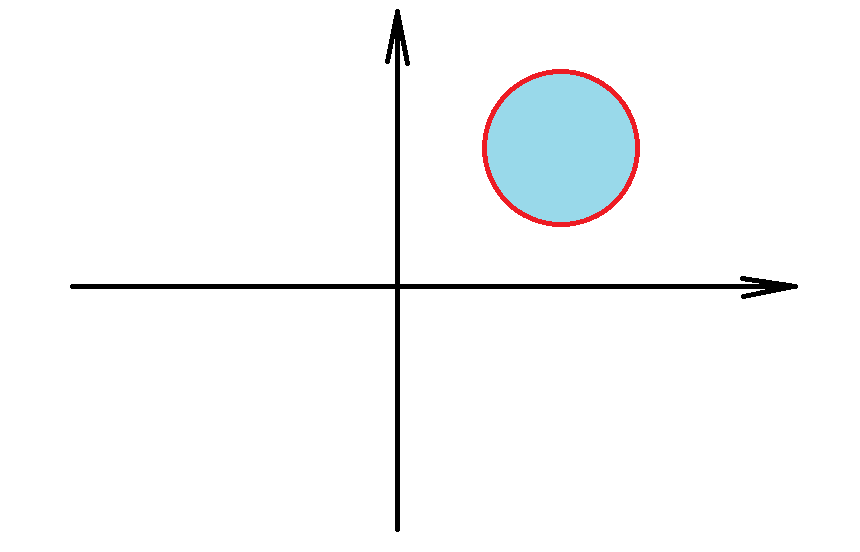

Example. Determine if the set is compact or not in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with Euclidean metric: \[X=\{(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;(x-1)^2+(y-1)^2 {\color{red}\leq} 1\}.\]

Solution. \(X\) contains all of its accumulation points so it is closed. It is contained in the ball \(B(0,10)\), so it is bounded. Therefore, by the previous theorem, it is compact.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

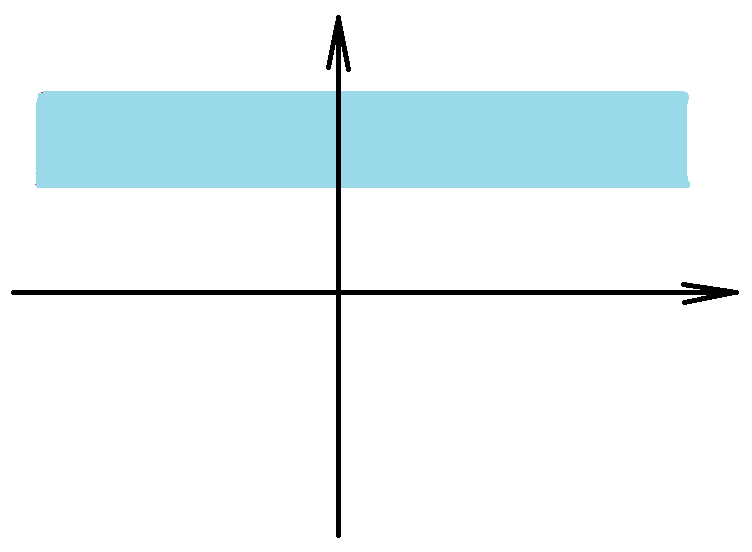

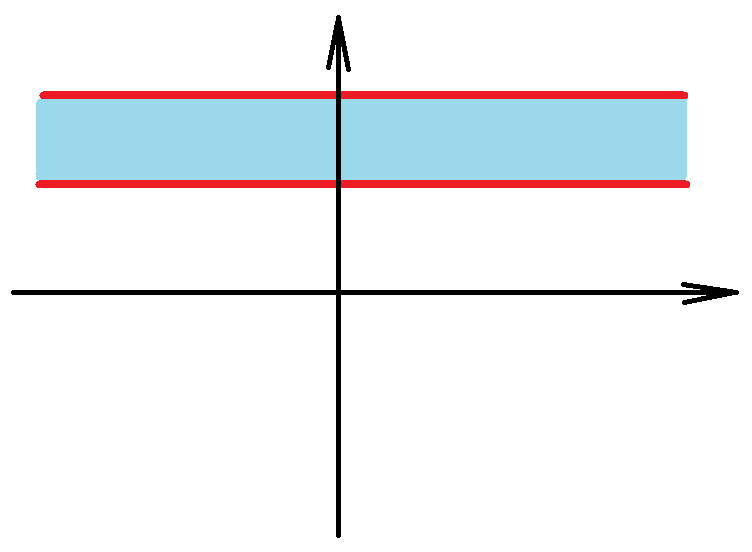

Example. Determine if the set \[X=\{(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2\;: 1<y<2\}\] is compact or not in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with Euclidean metric.

Solution. Note that \((0,2)\) is an accumulation point of \(X\), but \((0,2) \not\in X\). Therefore, \(X\) is not closed, so it is not compact.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Determine if the set \[X=\{(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2\;: 1 {\color{red}\leq} y {\color{red}\leq} 2\}\] is compact or not in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with Euclidean metric.

Solution. In can be checked that \(X\) is closed, although it is not contained in any ball, so it is not bounded, so it is not compact.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Examples

Example. Determine if the set \(\mathbb{Q}\) is compact in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Solution. \(\mathbb{Q}\) is not contained in any interval, so it is not compact.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Determine if the set \(\mathbb{Q} \cap [0,1]\) is compact in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Solution. \(\mathbb{Q}\) is contained in \((-1,2)\), but \({\rm cl\;}\mathbb{Q} \cap [0,1] =[0,1] \neq \mathbb{Q} \cap [0,1]\), so it is not closed, so it is not compact.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Perfect sets

Accumulation and isolated points

Accumulation point. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space, \(x \in X\) is called an accumulation point of \(E \subseteq X\) if for every open set \(U \ni x\) we have \[(E \setminus \{x\}) \cap U \neq \varnothing.\]

An accumulation point \(x\) of \(E \subseteq X\) is sometimes also called a limit point of \(E\) or a cluster point of \(E\).

Isolated point. A point \(x \in E\) is called an isolated point of \(E\) if it is not an accumulation point of \(E\).

Perfect sets

Perfect sets. We say that a subset \(E\) of a metric space \((X,\rho)\) is perfect if \(E\) is closed and every point of \(E\) is its limit point or equivalently \[E={\rm acc\;}E.\]

Theorem. Let \(\varnothing \neq P \subseteq \mathbb{R}^k\) be a perfect set. Then \(P\) is uncountable.

In the proof we will use the fact that we have just proved:

Proposition. Every closed and bounded set of \(\mathbb{R}^k\) is compact.

Proof. Since \(P\) has limit points, \(P\) must be infinite. In fact, for every \(x \in P\) and \(r>0\) \[B(x,r) \cap P \quad \text{ is infinite.}\]

Suppose not, i.e. there is \(x_0 \in P\) and \(r_0>0\) such that \[B(x_0,r_0) \cap P=\{x_1,\ldots,x_n\}.\]

Consider \[\rho(x_0,x_1), \ldots, \rho(x_0,x_n)\] and let \[r=\min_{1 \leq i \leq n}\rho(x_0,x_i)>0.\]

Then \[B(x_0,r) \cap P=\varnothing,\] thus \(x_0\) is not a limit point, contradiction.

Now we can assume \({\rm card\;}(P) \geq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\). Suppose for a contradiction that \({\rm card\;}(P)={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\), i.e. \(P=\{x_1,x_2,\ldots\}\).

Let \(V_1=B(x_1,r)\), then of course \(V_1 \cap P \neq \varnothing\). Suppose that \(V_n\) has been constructed so that \(V_n \cap P \neq \varnothing\).

Since every point of \(P\) is a limit point of \(P\) there is an open set \(V_{n+1}\) such that

\({\rm cl\;}(V_{n+1}) \subseteq V_{n}\),

\(x_{n} \not\in {\rm cl\;}(V_{n+1})\),

\(V_{n+1} \cap P \neq \varnothing\).

Let \(K_n={\rm cl\;}(V_n) \cap P\), this set is closed and bounded, thus compact. Since \(x_{n} \not\in K_{n+1}\), no point of \(P\) lies in \(\bigcap_{n=1}^{\infty}K_n\), but \(K_n \subseteq P\), so \[\bigcap_{n=1}^{\infty}K_n = \varnothing.\]

On the other hand, \(K_n \neq \varnothing\), compact, and \(K_{n+1} \subseteq K_n\), and the family \(K_n\) has a finite intesection property, i.e. any finite intersection of members of \((K_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is nonempty,

\[K_{n_1} \cap \ldots \cap K_{n_k} \neq \varnothing.\]

Thus \[\bigcap_{n=1}^{\infty}K_n \neq \varnothing,\] which is a contradiction. Hence \(P\) must be uncountable. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Corollary. Every interval \([a,b]\) with \(a<b\), and also \(\mathbb{R}\) are uncountable.

Connected sets

Separated and connected sets

Separated sets. Two subsets \(A\) and \(B\) of a metric space \((X,\rho)\) are said to be separated if both \[A \cap {\rm cl\;}(B)=\varnothing \quad \text{ and }\quad {\rm cl\;}(A) \cap B=\varnothing.\]

In other words, no points of \(A\) lies in the closure of \(B\) and vice versa.

Connected set. A set \(E \subseteq X\) is said to be connected if \(E\) is not a union of two nonempty separated sets.

Example.

\([0,1]\) and \((1,2)\) are not separated since \(1\) is a limit point of \((1,2)\).

However, \((0,1)\) and \((1,2)\) are separated.

Theorem

Theorem. \(E \subseteq \mathbb{R}\) is connected iff for all \(x,y \in E\) if \(x<z<y\), then \(z \in E\).

Proof (\(\Longrightarrow\)). If there exist \(x,y \in E\) and \(z \in (x,y)\) such that \(z \not\in E\), then \[E={\color{red}A_z} \cup {\color{blue}B_z}, \quad \text{ where }\quad {\color{red}A_z=E \cap (-\infty,z)} \quad \text{ and } \quad {\color{blue}B_z=E \cap (z,\infty)}.\] Since \(x \in A_z\) and \(y \in B_z\), then \(A_z \neq \varnothing\), \(B_z \neq \varnothing\) and also \(A_z \subseteq (-\infty,z)\), \(B_z \subseteq (z,\infty)\), so they are separated. Hence \(E\) is not connected.

Proof (\(\Longleftarrow\)). Conversely, suppose that \(E\) is not connected.

Then there are non-empty separated sets \(A,B\) such that \(A \cup B=E\).

Pick \(x \in A\) and \(y \in B\) and without loss of generality assume \(x<y\). Define \[z=\sup \left(A \cap [x,y]\right).\] hence \(z \in {\rm cl\;}(A)\) and \(z \not\in B\). In particular, \(x \leq z<y\).

If \(z \not\in A\) it follows \(x<z<y\) and \(z \not \in E\).

If \(z \in A\) then \(z \not \in {\rm cl\;}(B)\) hence there is \(z_1\) such that \(z<z_1<y\) and \(z_1 \not\in B\). Then \(x<z_1<y\) and \(z_1 \not\in E\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Prove that \(X=\mathbb{R} \setminus \{0\}\) is not connected.

Solution. We have \(-1,1 \in X\), but \(-1<0<1\) and \(0 \not\in X\), so \(X\) is not connected.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

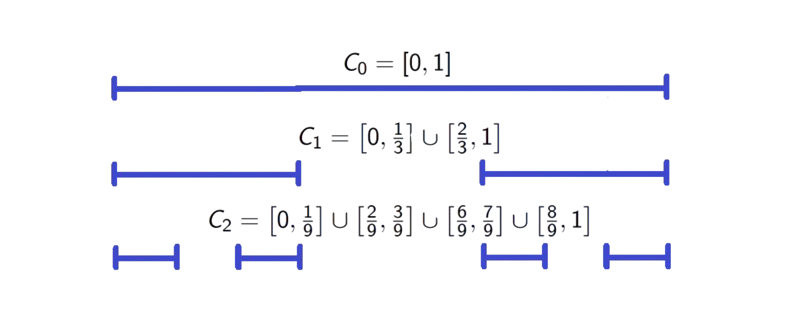

Cantor set

There exists a perfect set in \(\mathbb{R}\) which contains no segment.

Let \(C_0=[0,1]\). Given \(C_n\) that consist of \(2^n\) disjoint closed intervals each of length \(3^{-n}\) take each of these intervals and delete the open middle third to produce two closed intervals each of length \(3^{-n-1}\).

Take \(C_{n+1}\) to be the union of \(2^{n+1}\) closed intervals so formed and continue.

Cantor set

Cantor set. The set \[\mathcal{C}=\bigcap_{n=0}^{\infty}C_n\] is called the Cantor set or ternary Cantor set.

Each \(C_0 \supseteq C_1 \supseteq C_2 \supseteq \ldots\) is closed and bounded thus compact, and the family \((C_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) has finite intersection property thus the Cantor set is compact and \(\mathcal{C} \neq \varnothing\) .

Property (*). By the construction for each \(k,m \in \mathbb{N}\) we see that no segment of the form \[\left(\frac{3k+1}{3^m},\frac{3k+2}{3^m}\right) \quad \text{ has a point in common with $\mathcal{C}$. }\]

Properties of the Cantor set

Since every segment \((\alpha,\beta)\) contains a segment of the form (*) if \(m\) is sufficiently large, since the set \[\left\{\frac{\ell}{3^m}\;:\; m \in \mathbb{N} \text{ and }0 \leq \ell \leq 3^{m}-1\right\}\] is dense in \([0,1]\). Thus \(\mathcal{C}\) contains no segment \((\alpha,\beta)\). This also shows \({\rm int\;}\mathcal C=\varnothing\).

To prove that \(\mathcal{C}\) is perfect it is enough to show that \(\mathcal{C}\) contains no isolated point. Let \(x \in \mathcal{C}\) and let \(I_n\) be the unique interval from \(C_n\) which contains \(x \in I_n\). Let \(x_n\) be the endpoint of \(I_n\) such that \(x \neq x_n\). It follows from the construction of \(\mathcal{C}\) that \(x_n \in \mathcal{C}\). Hence \(x\) is a limit point of \(\mathcal{C}\) thus \(\mathcal{C}\) is perfect.

More about Cantor set

More about Cantor set

Each component of \(C_n\) can be described as the set

\[C_n=\left\{\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}\;:\; \varepsilon_j \in \{0,1,2\} \text{ and }\varepsilon_j \neq 1 \text{ for }1 \leq j \leq n\right\}.\].

Consequently,

\[{\color{teal}\mathcal{C}=\left\{\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}\;:\; \varepsilon_j \in \{0,2\} \right\}.}\].

Fact

Fact. Any number \(\sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}\) is uniquely determined by its sequence \(\varepsilon=(\varepsilon_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\) with \(\varepsilon_j \in \{0,2\}\).

Proof. Take \(\varepsilon=(\varepsilon_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\), \(\delta=(\delta_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\) with \(\varepsilon_j,\delta_j \in \{0,2\}\) such that \(\varepsilon \neq \delta\). Let \(N=\min\{j \in \mathbb{N}\;:\; \varepsilon_j \neq \delta_j\}\) and assume \(0=\varepsilon_N<\delta_N=2\). Then \[\begin{aligned} \sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}&= \sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}+\sum_{j=N+1}^{\infty}\frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j} \leq \sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}+\frac{2}{3^{N+1}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty}\frac{1}{3^j} \\&\leq \sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}+\frac{2}{3^{N+1}}\underbrace{\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{3}}}_{{\color{red}\frac{3}{2}}} =\sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}+\frac{1}{3^N}<\sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}+\frac{2}{3^N}\le \sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}. \end{aligned}\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remarks

Remark. We have two different representations \[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{3}&=\sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}=A, \quad \varepsilon_1=1, \quad \varepsilon_j=0 \quad\text{ for } \quad j \geq 2.\\ \frac{1}{3}&=\sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}=B, \quad \varepsilon_1=0, \quad \varepsilon_j=2 \quad \text{ for } \quad j \geq 2. \end{aligned}\]

There is a bijection \(\phi:\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}} \to \mathcal{C}\) defined by \[\phi(z)=\frac{2}{3}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty}\frac{z_j}{3^j} \quad \text{ for } \quad z=(z_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}, \quad z_j \in \{0,1\},\] and consequently \({\rm card\;}(\mathcal{C})={\rm card\;}(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R})=\mathfrak{c}.\)

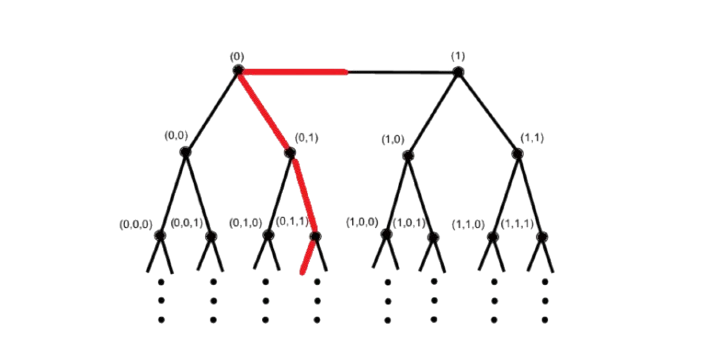

Cantor tree

\({\color{red}\varepsilon=(0,1,1,0,\varepsilon_4,\varepsilon_5,\ldots)}\)