2. Three important principles and their consequences PDF

The principle of induction

Well ordered sets

Well ordered set. If \((X,\leq)\) is linearly ordered, i.e. for every \(x, y\in X\) either \(x\le y\) or \(y\le x\), and every non-empty subset of \(X\) has a minimal (\(\equiv\) smallest) element, which is necessarily unique, \(X\) is said to be well ordered by \(\leq\); and \(\leq\) is called well ordering on \(X\).

Examples.

\((\mathbb{N}_0,\leq)\) is well ordered in contrast to \((\mathbb{Z},\leq)\) which is not well ordered.

Example 1. If \(A=\{21, 43, 65\}\), then the smallest element is \(21\).

Example 2. If \(A=\{2n:n\in \mathbb N_0\}\), then the smallest element is \(0\).

Well ordering principle and induction principle

Well ordering principle (or minimum principle). If \(A\) is a non-empty subset of non-negative integers \(\mathbb N_0\), then \(A\) contains the smallest number.

The principle of induction. If \(A\) is a set of non-negative integers such that

(Base step): \(0 \in A\)

(Induction step): Whenever \(A\) contains a number \(n\), it also contains the number \(n+1\).

Then \(A=\mathbb{N}_0\).

\[\forall_{A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0}\left(0 \in A \text{ and }\forall_{k \in \mathbb{N}}(k \in A \Longrightarrow (k+1) \in A) \text{ then }A=\mathbb{N}_0\right)\]

The maximum principle

Subset bounded from above. We say that \(A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0\) is bounded from above if there is \(M \in \mathbb{N}_0\) such that \(a \leq M\) for all \(a \in A\).

\[\exists_{M \in \mathbb{N}_0} \ \ \forall_{a \in A} \ \ a \leq M\]

The maximum principle. A non-empty subset of \(\mathbb{N}_0\), which is bounded from above contains the greatest number.

Induction principle: classical example

Exercise. Prove that for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\) we have \[\label{eq:n} \sum_{k=0}^{n}k=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}.\]

Solution. Let \(A\) be the set of \(n\) for which [eq:n] holds. \[A=\left\{n \in \mathbb{N}_0: \sum_{k=0}^{n}k=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right\}.\] Our goal is to show that \(A = \mathbb{N}_0\). We will use the induction principle. We have to check the base step and the induction step.

Solution

We verify (base step): \(0 \in A\). Indeed, one has \[\sum_{k=0}^0 k = 0 =\frac{0(0+1)}{2},\quad \text{ thus }\quad 0 \in A.\]

We verify (induction step): \(n \in A \Longrightarrow n+1 \in A\). If \(n \in A\), then \[{\color{blue} \sum_{k=0}^{n}k=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}.}\] Our goal is to prove that \(n+1 \in A\). We calculate \[\sum_{k=0}^{n+1}k={\color{blue}\sum_{k=0}^{n}k}+(n+1) ={\color{blue}\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}+(n+1)=\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2}.\]

Three equivalent statements

Three principles

Well ordering principle (A). If \(A\) is a non-empty subset of non-negative integers \(\mathbb N_0\), then \(A\) contains the smallest number.

The principle of induction (B). If \(A\) is a subset of non-negative integers \(\mathbb N_0\) such that

(Base step): \(0 \in A\).

(Induction step): Whenever \(A\) contains a number \(n\), it also contains the number \(n+1\).

Then \(A=\mathbb{N}_0\).

The maximum principle (C). A non-empty subset of \(\mathbb{N}_0\), which is bounded from above contains the greatest number.

Our goal

Our goal is to prove that the statements (A), (B), and (C) are equivalent.

In order to prove that, we will show:

(A) \(\Rightarrow\) (B)

(B) \(\Rightarrow\) (A)

(A) \(\Rightarrow\) (C)

(C) \(\Rightarrow\) (A)

(A) \(\Rightarrow\) (B)

If \(A\) is a set of non-negative integers such that

\(0 \in A\).

Whenever \(A\) contains a number \(n\), it also contains \(n+1\).

We want to establish \(A=\mathbb{N}_0\).

Suppose for contradiction that \(A \neq \mathbb{N}_0\). Then \(\mathbb{N}_0 \setminus A \neq \varnothing\). By well ordering principle (A) there is the smallest element \(m\) of \(\mathbb{N}_0 \setminus A\).

Since \(0 \in A\), we have \(m \neq 0\),

Observe that \(m-1 \in A\), because otherwise \(m-1 \in \mathbb{N}_0 \setminus A\), which contradicts the fact that \(m\) is the smallest element of \(\mathbb{N}_0 \setminus A\). But if \(m-1\in A\), then by (2) we have \(m \in A\), which is impossible.

The implication (A) \(\Rightarrow\) (B) follows. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

(B) \(\Rightarrow\) (A)

Let \(A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0=\{0,1,2,\ldots\}\) such that \(A \neq \varnothing\). Suppose for contradiction that \(A\) does not have a least element.

It is easy to see that \(0 \not\in A\), because otherwise it would be a minimal element of \(A\) (as \(0\) is the minimal element of \(\mathbb{N}_0\)).

We also see \(1 \not \in A\), otherwise it is a minimal element of \(A\).

We continue and assume that \(1,2,\ldots,n \not \in A\). Then \(n+1 \not\in A\), otherwise \(n+1\) is the smallest element of \(A\).

Now use the principle of induction and conclude that \(A =\varnothing\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

(A) \(\Rightarrow\) (C)

Suppose that \(A \neq \varnothing\) and bounded. \[\underbrace{\exists}_{\text{there exists}} M \in \mathbb{N}_0 \ \ \underbrace{\forall}_{\text{for all}} a \in A \ \ a \leq M\]

This means that \(M-a \geq 0\) for all \(a \in A\). Let us consider the set \[B=\{M-a\;:\; a \in A\} \neq \varnothing.\]

By the well ordering principle (A) there is \(b \in A\) such that \(M-b\) is the smallest element of \(B\).

Thus \[M-b \leq M-a\] for all \(a \in A\), equivalently \(a \leq b\) for all \(a \in A\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

(C) \(\Rightarrow\) (A)

Let \(A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0\), \(A \neq \varnothing\). We show that \(A\) has a minimal element. Let \[B=\{n \in \mathbb{N}_0\;:\; n \leq a \text{ for every }a\in A\}=\{n \in \mathbb{N}_0\;:\; \forall a \in A\ n \leq a \}\]

The set \(B\) is bounded and \(0 \in B\) since \(0 \leq n\) for any \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\). Thus, by the maximum principle (C) we are able to find \(b_0 \in B\) such that \(b_0\) is maximal in \(B\). We see \[\forall a \in A \ \ \forall b \in B \ \ b \leq b_0 \leq a.\]

The proof will be completed if we show \(b_0 \in A\).

Assume for contradiction \(b_0 \neq a\) and \(b_0 \leq a\) for all \(a \in A\). Thus \(b_0<a\) for all \(a \in A\). Hence \[b_0+1 \leq a\] for any \(a \in A\). Then \(b_0+1 \in B\), but \(b_0\) is the maximal element of \(B\), which gives contradiction.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Induction: example

Example. Prove that \(6\) divides the number \(7^n-1\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\).

Solution. Let \(A\) be the set of \(n\) for which \(6\) divides \(7^n-1\). \[A=\left\{n \in \mathbb{N}_0\;:\; 6 \text{ divides }7^n-1\right\}\]

Our goal is to show \(A = \mathbb{N}_0\). We will use the induction principle.

Base step. We have \(7^0-1=0\) hence \(6\) divides \(0\). Thus \(0 \in A\).

Induction step. We now verity that \(n \in A \Longrightarrow n+1 \in A\). Indeed, \[\begin{aligned} 7^{n+1}-1&=7^{n+1}-{\color{red}7^n}+{\color{red}7^n}-1 \\&=(7-1)7^n+7^n-1 \\=&\underbrace{6 \cdot 7^n}_{\text{divisible by }6}+\underbrace{7^n-1}_{\text{divisible by }6 \text{ since }n \in A} \end{aligned}\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Another example: Factorization theorem

Every integer \(n > 1\) is either a prime number or a product of prime numbers.

Proof.

Base step. The theorem is clearly true for \(n = 2\).

Induction step. Proceeding by induction on \(n>1\) we can assume that it is also true for every integer less than \(n\).

Then, if \(n\) is not prime, it has a positive divisor \(d\) such that \(1 < d < n\). Hence, \(n = cd\), where \(1<c < n\).

By induction each of \(c\) and \(d\) is a product of prime numbers by induction. Therefore, \(n\) is also a product of prime numbers.

$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Well ordering principle: example

Example. A sequence \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}_0}\) is given by \(a_0=-1\), \(a_1=0\), and \(a_{n+1}=5a_n-6a_{n-1}\) for \(n \geq 1\). Prove that \[a_n=2 \cdot 3^n-3 \cdot 2^n.\]

Solution. In the proof, we will use the well ordering principle. Let \(A\) be the set of integers \(n\in \mathbb N_0\) such that \(a_n\neq2 \cdot 3^n-3 \cdot 2^n\). We will show that \(A=\varnothing\). Suppose for a contradiction that \(A\neq\varnothing\) and let \(n_0\) be the smallest element of this set. Since \[a_0=2 \cdot 1 -3 \cdot 1=-1,\] \[a_1=2\cdot 3^1-3\cdot 2^1=0\] we have \(n_0 \neq 0,1\). By the minimality of \(n_0\) we have \[a_n=2 \cdot 3^n-3 \cdot 2^n\] for all \(0\le n<n_0\).

Solution

Using the reccurence definition \[a_{n_0}=5a_{n_0-1}-6a_{n_0-2}\] we obtain \[\begin{aligned} 2 \cdot 3^{n_0}-3 \cdot 2^{n_0}\neq a_{n_0}&=5a_{n_0-1}-6a_{n_0-2}\\ &=5 \cdot(2 \cdot 3^{n_0-1}-3 \cdot 2^{n_0-1})-6\cdot(2 \cdot 3^{n_0-2}-3 \cdot 2^{n_0-2})\\&=2 \cdot 3^{n_0}-3 \cdot 2^{n_0}, \end{aligned}\] which contradicts the minimality of \(n_0\). This shows that \(A=\varnothing\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Another example: The division algorithm

Let \(a, d\in\mathbb Z\) and \(d\neq0\). There exist unique integers \(q\) and \(r\) such that \[\begin{aligned} \label{eq:1} a = dq + r, \quad \text{where} \quad 0 \leq r <|d|. \end{aligned}\] In particular, \(d\mid a\) if and only if \(r=0\).

Proof.

Let \[S:=\{a - dq: q\in \mathbb Z\}\cap\mathbb N_0,\] and note that \(S\neq\varnothing\). Indeed,

If \(a \geq 0\), then \(a = a - d \cdot 0 \in S\).

If \(a < 0\), then \[a - d(d|d|^{-1}a) = (-a)(|d|-1) \in S.\]

$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Existence: By the minimum principle, \(S\) contains a smallest element \(r \in \mathbb N_0\), and \(a= dq+r\) for some \(q \in \mathbb{Z}\). If \(r \geq |d|\), then \[0 \leq r - |d| = a - d(q + d|d|^{-1}) < r,\] and \(r - |d| \in S\), which contradicts the minimality of \(r\) implying [eq:1].

Uniqueness: Let \(q_1, r_1, q_2, r_2\in\mathbb Z\) be integers such that \(a = dq_1 + r_1 = dq_2 + r_2\) and \(0 \leq r_1, r_2 <|d|\). If \(q_1 \neq q_2\), then \[|d|\le |d||q_1 - q_2| = |r_2 - r_1|<|d|.\] which is impossible. Therefore, \(q_1 = q_2\) and \(r_1 = r_2\) as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Square root of \(2\)

The equation \(p^2=2\) has no solution in rational numbers

Exercise. Prove that the equation \(p^2=2\) has no solution in rational numbers.

The rational numbers are \[\mathbb{Q}=\left\{\frac{n}{m}\;:\; n \in \mathbb{Z},\; m \in \mathbb{Z} \setminus \{0\} \right\}.\]

Relatively prime numbers. We say that \(m,n \in \mathbb{N}\) are relatively prime if there is no a number \(a \in \mathbb{N}\), \(a \neq 1\) such that \(a\) divides \(m\) and \(n\).

The numbers \(6\) and \(42\) are not relatively prime.

The numbers \(21\) and \(10\) are relatively prime.

The number \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\) is even if it is divisable by \(2\).

The number \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) is odd if it is not divisable by \(2\).

Proof.

Assume for a contradiction that there is \(p=\frac{m}{n} \in \mathbb{Q}\) such that \(m,n\) are relatively prime and \[p^2=\left(\frac{m}{n}\right)^2=2.\]

Equivalently, we obtain an equation in integers: \[m^2=2n^2.\]

This implies that \(m\) is even. (If \(m\) was odd then \(m^2\) would be odd.)

Since \(m\) is even, then \(2n^2\) must be divisable by \(4\).

Consequently, \(n\) is also even.

Thus, \(m,n\) are both even, so they are divisable by \(2\).

This means that \(m,n\) are not relatively prime.

Contradiction!$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The solution of \(p^2=2\)

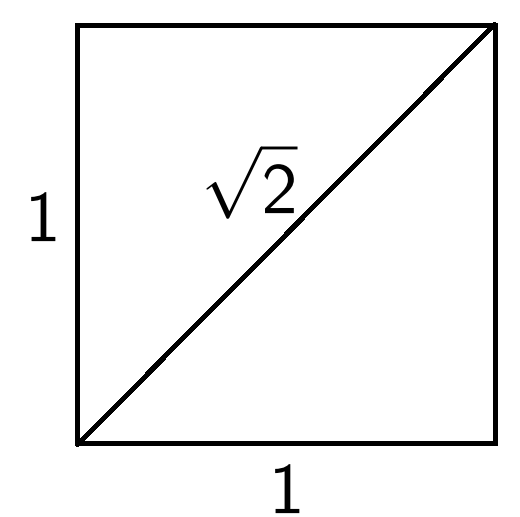

The solution of \(p^2=2\) exists as a geometric length of the diagonal of the square of side-length 1.

Sets without minimal and maximal elements

Let \[A=\{p \in \mathbb{Q}\;:\;p>0,\; p^2<2\},\] \[B=\{p \in \mathbb{Q}\;:\;p>0,\; p^2>2\},\]

We will show that:

\(A\) contains no largest number,

\(B\) contains no smallest number.

It is also easy to see that \[\mathbb Q_+=\{x\in \mathbb Q: x>0\}=A\cup B.\]

Remark. The sets \(A\) and \(B\) illustrate that neither well-ordering principle nor maximum principle is true in \(\mathbb Q\).

Set \(A\)

Claim. \(A\) contains no largest number means that for every \(p \in A\) we can find \(q \in A\) such that \(p<q\).

Set \(B\)

Claim. \(B\) contains no smallest number means that for every \(p \in B\) we can find \(q \in B\) such that \(q<p\).

Concepts of largeness and smallness

Concepts of largeness and smallness

Archimedian property on \(\mathbb{Q}\).

Given any number \(x \in \mathbb{Q}\) there exists \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) satisfying \[n>x.\]

Given any rational number \(y>0\) there exists an \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) satisfying \[\frac{1}{n}<y.\]

The second property follows from the first one by taking \(x=\frac{1}{y}\). Thus it suffices to prove the first statement.

If \(x\in \mathbb{Q}\) and \(x\le 0\), then there is nothing to do. Suppose that \(x>0\), then \(x=\frac{p}{q}\) for some \(p, q\in \mathbb{N}\). Consider the set \[A=\{n\in\mathbb{N}_0: n\le x\}.\]

This set is nonempty since \(x>0\). We see that \(m\in A\) iff \(p-qm\ge0\). Consider now the set \[B=\{p-qn: n\in A\}\subset \mathbb N_0, \qquad \text{ and } \qquad B\neq \varnothing.\]

By the well-ordering principle \(B\) contains the smallest element, say \(p-qm_0\) for some \(m_0\in A\). Thus for all \(n\in A\) we have \[p-qm_0\le p-qn \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad n\le m_0\le x.\]

Now we see that \(x< m_0+1\) has desired property.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$