20. Exponential Function and Natural Logarithm Function; Power Series and Taylor's theorem PDF

The exponential function

The exponential function

The exponential function. We define \[E(z)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{z^n}{n!}, \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in \mathbb{C}.\]

Observe that \(|E(z)| \leq \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{|z|^n}{n!}<\infty.\) The ratio test shows that the series converges absolutely for any \(z \in \mathbb{C}\) and \(E(z)\) is well defined.

Recall. If \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n\) converges absolutely, \({\color{red}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n=A}\), and \({\color{blue}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}b_n=B}\), and \[c_n=\sum_{k=0}^n a_kb_{n-k}, \quad \text{ for } \quad n=0,1,2,\ldots .\] Then \(\sum_{k=0}^\infty c_k={\color{red}A}{\color{blue}B}\).

Properties of the exponential function 1/4

Applying this result to absolutely convergent series \(E(z)\), \(E(w)\) we obtain

(*). \[E(z)E(w)=E(z+w) \quad \text{ for } \quad z,w \in \mathbb{C}.\]

Proof of (*). Indeed, \[\begin{aligned} E(z)E(w)&=\left(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{z^n}{n!}\right)\left(\sum_{m=0}^{\infty}\frac{w^m}{m!}\right) \underbrace{=}_{{\color{red}Recall}}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{z^kw^{n-k}}{k!(n-k)!} \\&=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n!}\sum_{k=0}^n {n \choose k}z^kw^{n-k}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(z+w)^n}{n!}=E(z+w). \end{aligned}\] In the last line we have used the Binomial theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Properties of the exponential function 2/4

As the consequence we obtain

(**). \[E(z)E(-z)=E(z-z)=E(0)=1.\]

This shows that \(E(z) \neq 0\) for all \(z \in \mathbb{C}\).

We have \(E(x)>0\) if \(x>0\), giving \(E(x)>0\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) by (**).

It is easy to see that \[\lim_{x \to \infty}E(x)=+\infty\quad \text{ since } \quad E(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{x^n}{n!}.\]

Consequently by (**) we obtain \[\lim_{x \to \infty}E(-x)=0\quad \text{ since } \quad E(-x)=\frac{1}{E(x)}.\]

Properties of the exponential function 3/4

If \(0<x<y\) then \[E(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{x^n}{n!}<\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{y^n}{n!}=E(y).\]

Since \(E(x)E(-x)=1\) thus \[E(-y)<E(-x),\] hence \(E\) is strictly increasing on \(\mathbb{R}\).

If \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) then \[E'(x)=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{E(x+h)-E(x)}{h}=E(x)\underbrace{\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{E(h)-1}{h}}_{{\color{red}=1}}=E(x).\]

Properties of the exponential function 4/4

Indeed, \[\frac{E(h)-1}{h}=\frac{1}{h}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{h^n}{n!}=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{h^{n-1}}{n!},\]

hence \[\begin{aligned} \left|\frac{1}{h}(E(h)-1)-1\right| &\leq \sum_{n=2}^{\infty}\frac{|h|^{n-1}}{n!}=|h|\sum_{n=2}^{\infty}\frac{|h|^{n-2}}{n!}\\ &\leq |h|E(|h|) \underbrace{\leq}_{{\color{red}|h| \leq 1}} |h|e \ _{\overrightarrow{h \to 0}}\ 0. \end{aligned}\]

We have proved that \(E'(x)=E(x)\) for all \(x\in\mathbb R\).

In particular, \(E\) is continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\).

In the next theorem we summarize what we have proved.

Theorem

Theorem. The function \[E(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{x^n}{n!}\] is called the exponential function and is usually denoted by \(e^x=E(x)\). The exponential function \(\mathbb R\ni x\mapsto e^x\) satisfies the following properties:

\(e^x\) is continuous and differentiable for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\),

\((e^x)'=e^x\),

\(e^x\) is strictly increasing on \(\mathbb{R}\) and \(e^x>0\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\),

\(e^xe^y=e^{x+y}\) for all \(x, y\in\mathbb R\),

\(\lim_{x \to +\infty}e^x=+\infty\) and \(\lim_{x\to -\infty}e^{x}=0\),

\(\lim_{x \to +\infty}x^{n}e^{-x}=0\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Proof. We have proved (a)-(e). We only prove (f).

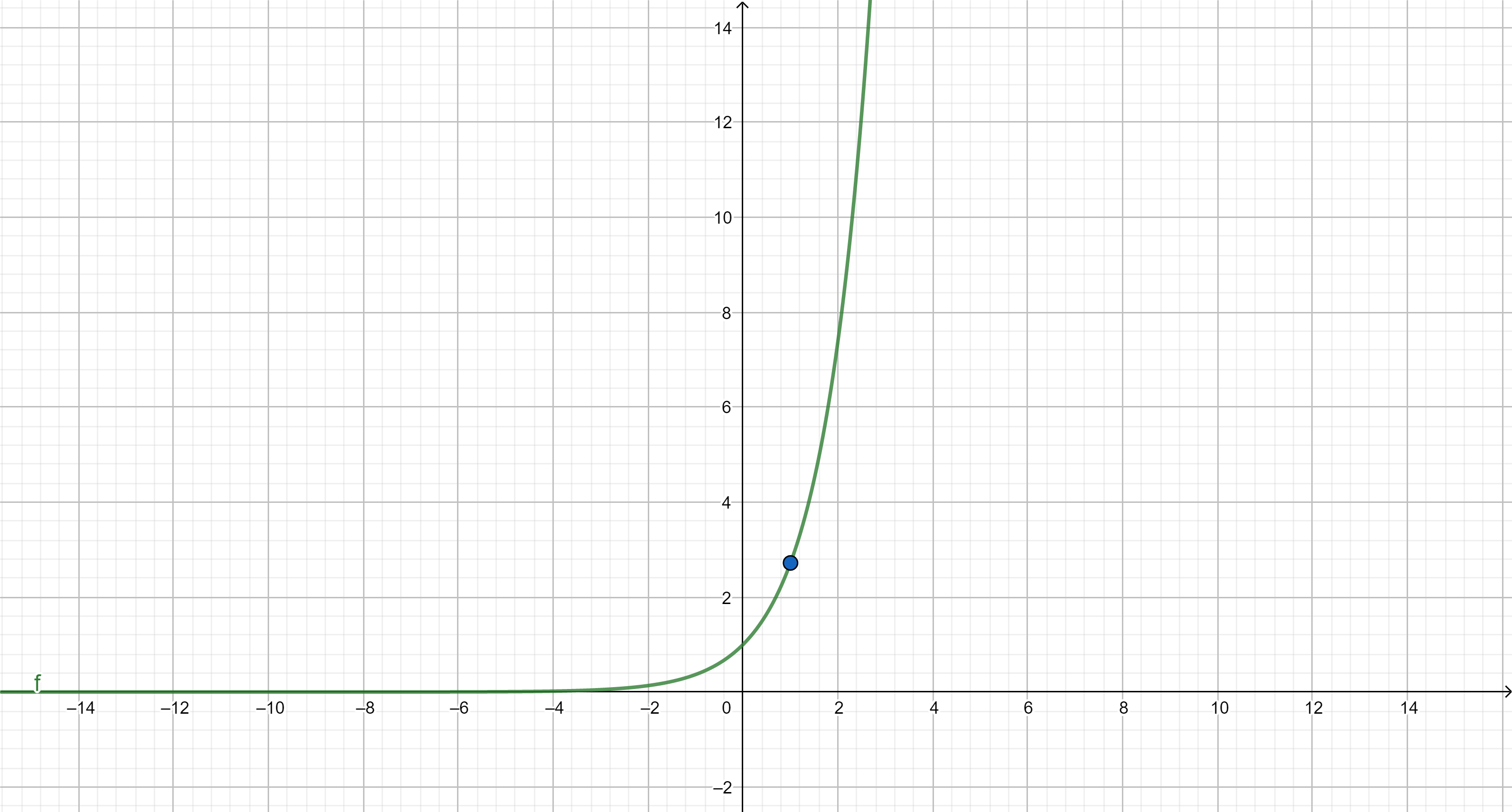

Graph of \(f(x)=e^x\)

Note that \[e^x=\sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\frac{x^k}{k!}>\frac{x^{n+1}}{(n+1)!},\] so that \[x^ne^{-x}<\frac{(n+1)!}{x}\ _{\overrightarrow{x \to \infty}}\ 0,\] which gives the desired claim.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark. Item (f) says that \(e^x\) tends to \(+\infty\) faster that any polynomial.

If \(P(x)=\sum_{k=0}^nc_kx^k\), where \(c_1,\ldots,c_n \in \mathbb{R}\), then \[0 \leq \left|\frac{P(X)}{e^x}\right| \leq \frac{\sum_{k=0}^n|c_k|x^k}{e^x} \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to \infty}}\ 0.\]

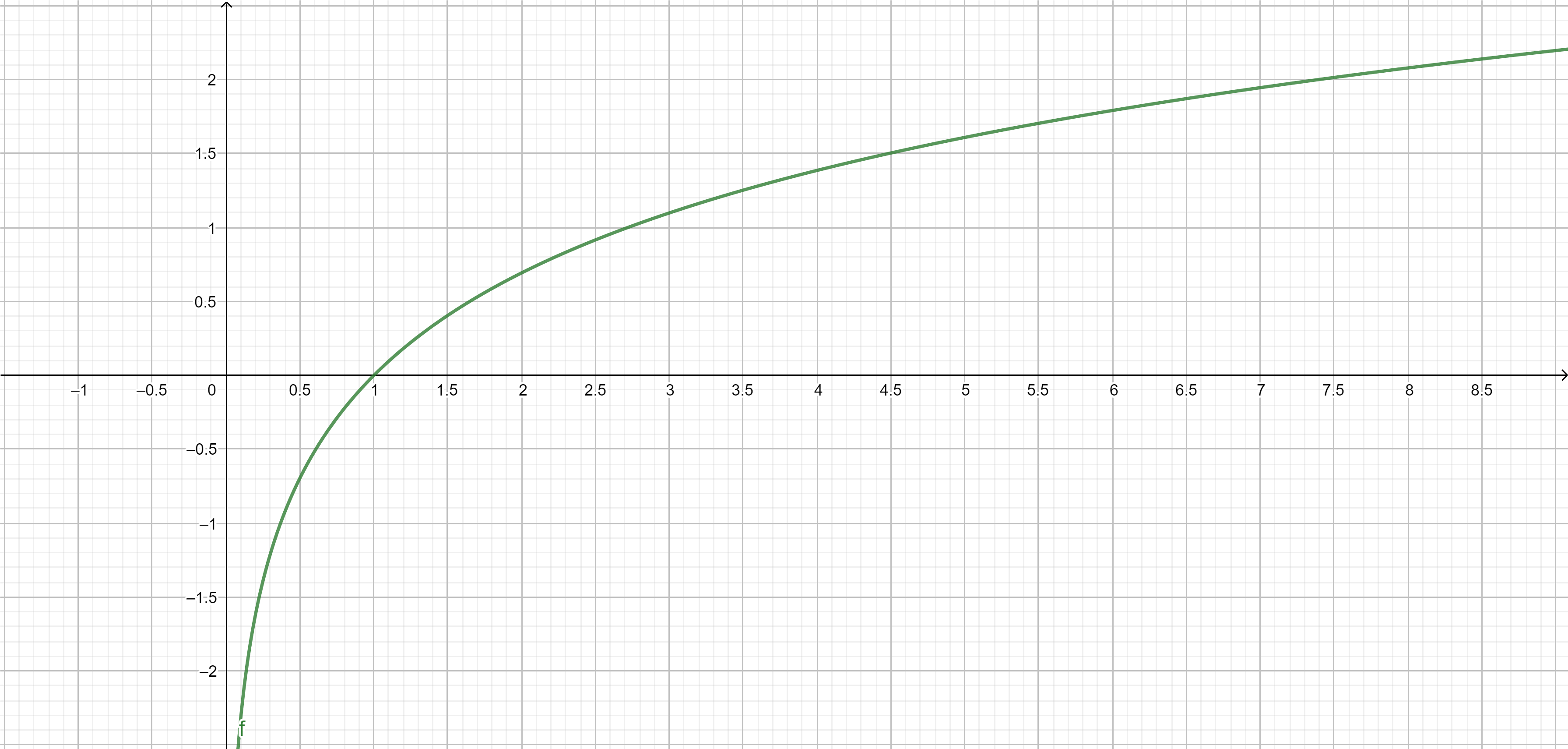

The logarithm function

The logarithm function 1/4

Since the exponential function \(E(x)=e^x\) is strictly increasing and differentiable on \(\mathbb{R}\) it has an inverse function \(L\), which is also strictly increasing and differentiable and whose domain is \(E[\mathbb{R}]=(0,\infty)\).

\(L\) is defined by \[E(L(y))=y \quad \text{ for all }\quad y>0\] or, equivalently, \(L(E(x))=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Differentiating the latter equation \[1=(x)'=(L(E(x)))'=L'(E(x))E'(x)=L'(E(x))E(x).\] Thus \(L'(E(x))=\frac{1}{E(x)}\), hence

\[L'(y)=\frac{1}{y} \quad \text{ for all }\quad y>0.\]

The logarithm function 2/4

Writing \(u=E(x)\) and \(v=E(y)\) note that \[\begin{aligned} L(uv)=L(E(x)E(y))&=L(E(x+y))\\ &=x+y=L(u)+L(v)\quad \text{ for }\quad u,v>0. \end{aligned}\]

From now on we will write \({\color{red}\log(x)=L(x)}\).

Since \(\lim_{x \to +\infty}e^x=+\infty\) and \(\lim_{x \to -\infty}e^x=0\), we conclude \[\lim_{x \to \infty}\log(x)=+\infty,\quad \text{ and }\quad \lim_{x \to 0}\log(x)=\infty.\]

Observe also that \(\lim_{n\to \infty}\big(1+\frac{x}{n})^n=e^x\). By L’Hôpital’s rule we have \[\lim_{n\to \infty}\frac{\log\big(1+\frac{x}{n})}{\frac{1}{n}}= \lim_{y\to 0}\frac{\log\big(1+xy)}{y}=\lim_{y\to 0}\frac{x}{1+xy}=x.\]

The logarithm function 3/4. Definition of \(x^{\alpha}\)

Since \(x=E(L(x))\), it is easily seen that \[x^n=E(nL(x)) \quad \text{ and }\quad x^{1 / m}=E\left(\frac{1}{m}L(x)\right) \quad \text{ for }\quad n,m \in \mathbb{N}.\] Thus \[x^{\alpha}=E(\alpha L(x)) \quad \text{ if }\quad \alpha \in \mathbb{Q}.\]

It also makes sense to define \[x^{\alpha}=E(\alpha L(x)) \quad \text{ for }\quad \alpha \in \mathbb{R} \quad \text{ and }\quad x>0.\]

The continuity and monotonicity of \(E\) and \(L\) show that everything makes sense and this definition coincides with

\[x^{\alpha}=\sup\{x^p\;:\;p<\alpha, \ p \in \mathbb{Q}\} \quad \text{ if }\quad \alpha \in \mathbb{R}\quad \text{ and }\quad x>1.\]

The logarithm function 4/4

If we differentiate \[x^{\alpha}=E(\alpha L(x)),\] then \[(x^{\alpha})'=E'(\alpha L(x))\frac{\alpha}{x}={\color{blue}\alpha x^{\alpha-1}}.\]

Finally note that \[\lim_{x \to \infty}x^{-\alpha}\log(x)=0\quad \text{ for every }\quad \alpha>0.\] That is, \(\log(x)\) tends to \(+\infty\) slower that any power of \(x\).

Indeed, since \(x^{\alpha} \ _{\overrightarrow{x \to \infty}}\ +\infty\), by L’Hôpital’s rule \[\lim_{x \to \infty}\frac{\log(x)}{x^{\alpha}}\underbrace{=}_{{\color{red}L'H{{o}}pital}}\lim_{x \to \infty}\frac{\frac{1}{x}}{\alpha x^{\alpha-1}}=\lim_{x \to \infty}\frac{1}{\alpha x^{\alpha}}=0.\]

Applications

Euler–Mascheroni constant

Divergence of harmonic series. \[\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n}=+\infty.\]

Theorem. The sequences \[{\color{blue}a_n=\sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{k}-\log(n) \quad \text{ and } \quad b_n=\sum_{k=1}^{n}\frac{1}{k}-\log(n)}\] are increasing and decreasing respectively and bounded, and \[\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=\gamma.\] where \(\gamma\) is known as the Euler (or Euler–Mascheroni) constant.

Remark.

It is not even known whether \(\gamma\) is irrational.

\(\gamma\) is called Euler-Mascheroni constant, and \(\gamma \simeq 0,5772\ldots\).

Proof. We know \[\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)^n<e<\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)^{n+1}\] thus \[n \log\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)<1<(n+1)\log\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right),\] and consequently \[\log\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)<\frac{1}{n},\] \[\log\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)>\frac{1}{n+1}.\]

Thus \[\begin{aligned} a_{n+1}-a_n=\sum_{k=1}^{n}\frac{1}{k}-\log(n+1)-\sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{k}+\log(n)= \frac{1}{n}-\log\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)>0. \end{aligned}\] Hence \((a_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\) is increasing. Similarly,

\[\begin{aligned} b_{n+1}-b_n=\frac{1}{n+1}-\log\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)<0, \end{aligned}\] thus \((b_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\) is decreasing. Also it is clear \[a_1 \leq a_n \leq b_n \leq b_1.\] Thus by the (MCT) the limits exist \[\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=\gamma,\] since \(b_n=a_n+\frac{1}{n}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proposition

Proposition. For \(x>0\) one has \[\frac{x}{x+1}<\frac{2x}{x+2} \leq \log(x+1)<x.\]

Proof. Let \(f(x)=x-\log(1+x)\), then

\[f(0)=0,\] \[f'(0)=1-\frac{1}{x+1}>0\quad \iff\quad x>0\] thus \(f\) is increasing for \(x>0\). Hence \(f(x)>f(0) \text{ for }x>0\), so \[\log(1+x)<x.\]

We now consider \[h(x)=\log(1+x)-\frac{2x}{x+1}\quad \text{ for }\quad x>0.\] Note that \(h(0)=0\) and \[h'(x)=\frac{x^2}{(x+1)(x+2)^2}>0\quad \text{ for }\quad x>0.\] Thus \(h\) is increasing for \(x>0\) and \[h(x)>h(0)=0.\] Consequently \[\log(1+x)>\frac{2x}{x+2}>\frac{x}{x+1}\] for \(x>0\) as desired.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

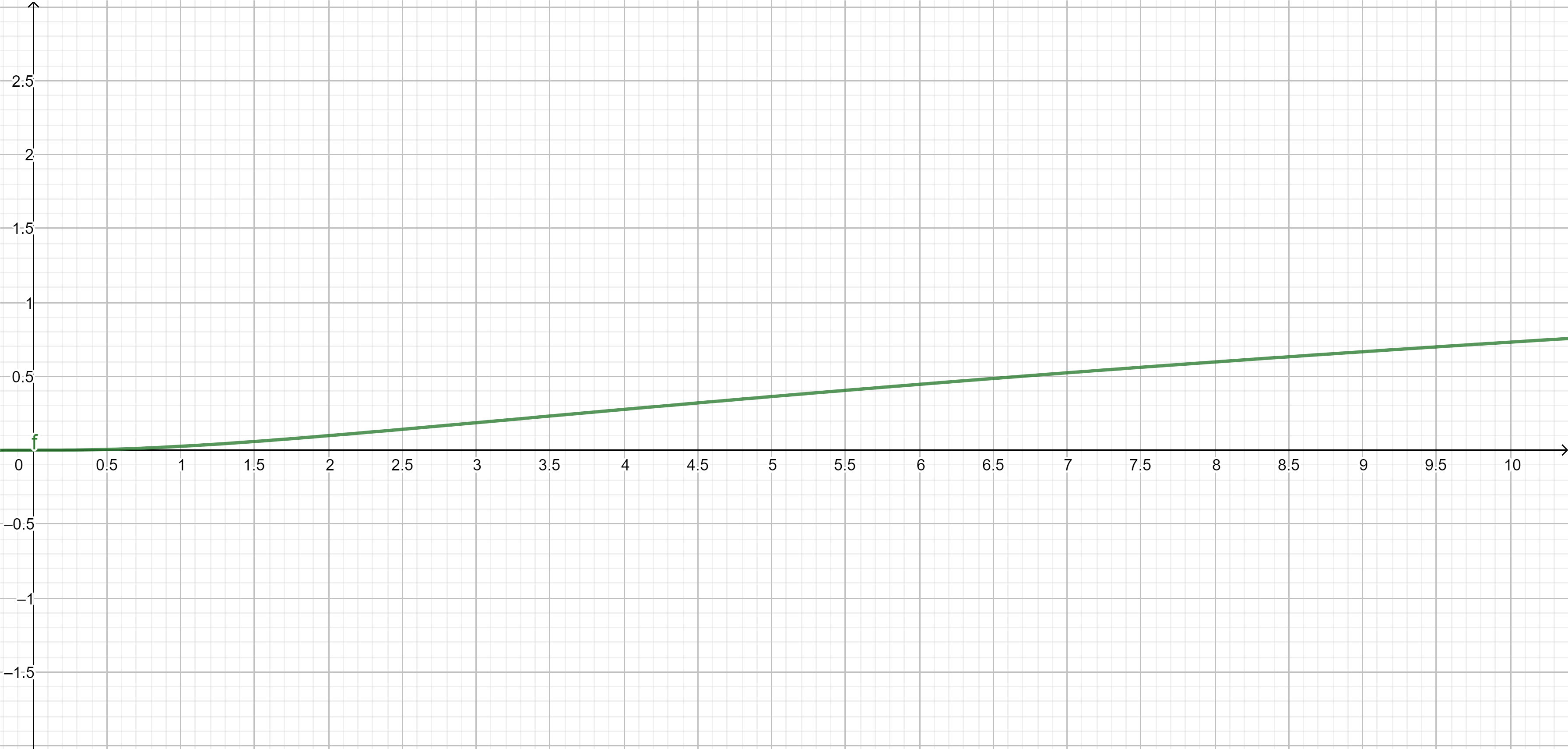

Graph of the function \(\log(x+1)-\frac{2x}{x+2}\)

Application

Application. \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\left(\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{n+1}+\ldots+\frac{1}{2n}\right)=\log 2.\]

Proof. Note that \[\frac{1}{n+1}<\log\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)<\frac{1}{n} \quad \text{ for }\quad n>1\] upon taking \({\color{blue}x=\frac{1}{n}}\) in \(\frac{x}{x+1}<\log(1+x)<x.\) Consequently \[\log\left(\frac{2n+1}{n}\right)<\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{n+1}+\ldots+\frac{1}{2n}<\log\left(\frac{2n}{n-1}\right).\] Thus \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\left(\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{n+1}+\ldots+\frac{1}{2n}\right)=\log 2.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Inequalities between weighted means

Theorem. If \(x_1,\ldots,x_k>0\) and \(\alpha_1,\ldots,\alpha_k>0\) and \(\sum_{j=1}^k\alpha_j=1\), then \[x_1^{\alpha_1}\cdot \ldots \cdot x_k^{\alpha_k} \leq \alpha_1x_1+\ldots+\alpha_kx_k.\]

Proof. Let \(f(x)=\log(x)\) and note that \[f'(x)=\frac{1}{x}\quad \text{ and }\quad f''(x)=\frac{-1}{x^2}<0.\] Thus \(f''(x)<0\) for all \(x>0\) which means that \(f\) is concave. In other words, for all \(x_1,\ldots,x_k>0\) and \(\alpha_1,\ldots,\alpha_k>0\) obeying condition \(\alpha_1+\ldots+\alpha_k=1\), we have \[f(\alpha_1 x_1+\ldots+\alpha_k x_k) \geq \alpha_1 f(x_1)+\ldots+\alpha_k f(x_k).\]

Consequently, we have \[\log(x_1^{\alpha_1}\cdot \ldots \cdot x_k^{\alpha_k})=\sum_{j=1}^k \alpha_j \log(x_j) \leq \log\left(\sum_{j=1}^k\alpha_jx_j\right)\] if and only if \[\qquad \qquad \qquad x_1^{\alpha_1}\cdot \ldots \cdot x_k^{\alpha_k} \leq \sum_{j=1}^k \alpha_j x_j. \qquad \qquad \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Corollary

Corollary. If \(p,q>0\) satisfy \(\frac{1}{p}+\frac{1}{q}=1\) and \(x,y>0\), then \[xy \leq \frac{1}{p}x^p+\frac{1}{q}y^q.\]

Proof. If suffices to apply the previous result with \(\alpha_1=\frac{1}{p}\), \(\alpha_2=\frac{1}{q}\) and \(x_1=x^p\), \(x_2=y^q\), then we obtain

\[xy=x_1^{1 / p}x_2^{1 / q} \leq \frac{1}{p}x_1+\frac{1}{q}x_2=\frac{1}{p}x^p+\frac{1}{q}y^q.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Remark. The inequality above is the key in the proof of Hölder’s inequality.