21. Power series of trigonometric functions done right; Fundamental Theorem of Algebra; and Taylor expansions of other important functions and applications PDF

Power series

Power series

Power series. Given a sequence \((c_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}_0}\), where \(c_n \in \mathbb{R}\), the series \[{\color{blue}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n, \ \ x \in \mathbb{R}}\] is called a power series.

The numbers \(c_n\) are called the coefficients of the series.

Example 1. \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}x^n\).

Example 2. \(e^x=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{x^n}{n!}\).

Radius of convergence

Radius of convergence. Given the power series \[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n\] set \[{\color{red}\alpha=\limsup_{n \to \infty}\sqrt[n]{|c_n|}, \quad \text{ and } \quad R=\frac{1}{\alpha}}.\] If \(\alpha=0\), then \(R=+\infty\).

The number \(R\) is called the radius of convergence of \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n\).

Theorem

Theorem. The series \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_nx^n\)

converges if \(|x|<R\), and

diverges if \(|x|>R\).

Proof. Consider \(a_n=c_nx^n\) and apply the root test \[\limsup_{n \to \infty}\sqrt[n]{|a_n|}=|x|\limsup_{n \to \infty}\sqrt[n]{|c_n|}=\frac{|x|}{R}.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Example 1. \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}n^nx^n\) has \(R=0\)

Example 2. \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{x^n}{n!}\) has \(R=+\infty\), since \(\alpha=\limsup_{n \to \infty}\sqrt[n]{\frac{1}{n!}}=0.\)

Examples

Example 3. \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}x^n\) has \(R=1\). If \(|x|=1\) the series \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}x^n\) diverges. We also know \[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}x^n=\frac{1}{1-x}\quad \text{ if }\quad |x|<1.\]

Example 4. \(\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{x^n}{n}\) has \(R=1\). If \(x=1\) the series diverges since \(\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n}=+\infty.\) If \(x=-1\) then the series converges since \[\bigg|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{n}\bigg|<\infty.\]

Trigonometric functions: sine and cosine

\(C\) and \(S\) functions

Recall that \(i^2 = -1\). Let us define \[\begin{aligned} C(x) &= \frac{1}{2}\cdot (E(ix) + E(-ix)), \quad \text { and }\\ S(x) &= \frac{1}{2i} \cdot (E(ix) - E(-ix)) \end{aligned}\]

We shall show that \(C(x)\) and \(S(x)\) coincide with the functions \(\cos(x)\) and \(\sin(x)\), whose definition is usually based on geometric considerations.

It is easy to see that \(E(\overline{z}) = \overline{E(z)}\), since \[E(z) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{z^n}{n!}.\]

Hence, we have \(\overline{C(x)} = C(x)\) and \(\overline{S(x)} = S(x)\), so \(C(x)\) and \(S(x)\) are real for \(x \in \mathbb R\). Recall that a number \(z \in \mathbb C\) is real if \(z = \overline{z}\), and the outputs of the functions \(C(x)\) and \(S(x)\) satisfy this relation.

Euler’s formula

Also Euler’s formula holds \[E(ix) = C(x) + iS(x)\quad \text{ if } \quad x\in\mathbb R.\]

Moreover, \(|E(ix)| = 1\) for any \(x \in \mathbb R\), since \[|E(ix)|^2 = E(ix)\overline{E(ix)} = E(ix)E(-ix) = 1.\]

Since \[C(x) = \frac{1}{2}(E(ix) +E(-ix)) \quad \text{ and }\quad S(x) = \frac{1}{2i}(E(ix) - E(-ix))\] we can read off that \(C(0) = 1\) and \(S(0)=0\) and also \[C'(x) = -S(x) \quad \text{ and } \quad S'(x) = C(x)\] Since \[C'(x) = \frac{1}{2}(iE(ix) - iE(-ix)) = \frac{i}{2}(E(ix) - E(-ix)) = -S(x).\]

Zeroes of the function \(C\) and definition of \(\pi\)

We assert that there exist positive numbers \(x\) such that \(C(x) = 0\).

If not, since \(C(0) = 1\), it follows that \(C(x) >0\) for all \(x>0\). If \(C(x_1)<0\) for some \(x_1>0\), then by the intermediate value theorem, since \(C\) is continuous, \(C(x_2) = 0\) for some \(0< x_2 < x_1\), contradiction!

Hence \(S'(x)>0\) since \[S'(x) = C(x).\] But \(S(0) = 0\), thus \(S(x)\) is strictly increasing on \((0,\infty)\).

By the mean–value theorem \[C(y) - C(x) = -(y-x)\cdot S(\theta_{x,y}) \quad \text{ for some } \quad \theta_{x,y} \in (x,y)\] thus \[C(x) - C(y) = (y-x) \cdot S(\theta_{x,y}) > (y-x) S(x)\] and since \(|C(x)|\le 1\) and \(|S(x)|\le 1\) we conclude \[(y-x)S(x) \leq C(x) - C(y) \leq 2.\]

But this is impossible if \(y\) is large since \(S(x) > 0\).

Let \(x_0>0\) be the smallest number such that \(C(x_0) = 0\). This exists since \(C(0) =1\) and the set of zeroes is closed.

We define the number \(\pi\) to be \[\pi = 2x_0.\]

Then \(C(\frac{\pi}{2}) = 0\) and since \(|E(ix)| = 1\) we deduce \[S\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right) = \pm 1.\]

Since \(C(x)>0\) in \((0, \frac{\pi}{2})\), \(S\) is increasing in \((0,\frac{\pi}{2})\). Hence \(S(\frac{\pi}{2}) = 1\).

Thus we have \[E\left(\frac{\pi i}{2}\right) = i.\]

Since \(E(z+w) = E(z)E(w)\) thus we have \[E(\pi i) = -1 \quad \text{ and } \quad E(2\pi i) = 1,\] hence \(E(z+2\pi i) = E(z)\) for all \(z \in \mathbb C\).

Theorem

The exponential function \(E:\mathbb C\to \mathbb C\) is periodic with period \(2\pi i\).

The functions \(S\) and \(C\) are periodic with period \(2 \pi\).

If \(0<t<2\pi\), then \(E(it) \neq 1\).

If \(z \in \mathbb C\) and \(|z| = 1\), there is a unique \(t \in (0,2\pi)\) such that \(E(it) = z\)

Proof.

Item (i) easily follows since \(E(z + 2\pi i) = E(z)\) for all \(z \in \mathbb C\). Since \(C(x) = \frac{1}{2}(E(ix) + E(-ix))\) we see \[\begin{aligned} C(x+2\pi) &= \frac{1}{2}(E(i(x+2\pi)) + E(-i(x+2\pi)))\\ &= \frac{1}{2}(E(ix) + E(-ix)) = C(x). \end{aligned}\] Similarly, \(S(x) = S(x+2\pi)\). Thus (ii) is proved.

To prove (c) suppose \(0 < t< \frac{\pi}{2}\) and \[E(it) = x+iy \quad \text{ with } \quad x,y \in \mathbb R.\]

Our preceding discussion shows that \(0<x<1\) and \(0<y<1\).

Now note that \(0<t<\frac{\pi}{2} \iff 0<4t<2\pi\) and that \[\begin{aligned} E(4it) = E(it)^4 = (x+iy)^4 = x^4 -6x^2y^2 +y^4 + 4ixy(x^2-y^2) \end{aligned}\]

If \(E(4it) \in \mathbb R\), then it follows that \(x^2 - y^2 = 0\). We are only considering real \(E(4it)\) because if \(E(4it)\) is imaginary, then it clearly is not equal to \(1\). Since \[|E(it)| = 1=x^2 + y^2,\] so we have \(x^2 = y^2 = \frac{1}{2}\). Hence \(E(4it) = -1\) and we are done.

To prove (iv), if \(0 \leq t_1 < t_2 < 2\pi\), then uniqueness follows, since \[E(it_2) E(it_1)^{-1} = E(i(t_2-t_1)) \neq 1.\]

To prove the existence we fix \(z \in \mathbb C\) so that \(|z| = 1\). Write \(z = x + iy\) with \(x,y \in \mathbb R\). Suppose first that \(x \geq 0\) and \(y\geq 0\).

\(C(t)\) decreases on \([0, \frac{\pi}{2}]\) from \(1\) to \(0\). Hence \(C(t) = x\) for some \(t \in [0, \frac{\pi}{2}]\). Since \(C^2 + S^2 = 1\) and \(S\geq 0\) on \([0, \frac{\pi}{2}]\), then \(z = E(it)\).

If \(x< 0\) and \(y \geq0\), the preceding conditions are satisfied by \(-iz\). Hence \(-iz = E(it)\) for some \(t \in [0, \frac{\pi}{2}]\).

Since \(i = E\left(\frac{\pi i}{2}\right)\) we obtain \[z = E\left(i \left(t+\frac{\pi}{2}\right)\right).\]

If \(y<0\), the preceding two cases show that \(z = E(it)\) for some \(t \in (0,\pi)\). Thus, \(z = -E(it) = E(i(t+\pi))\) since \(E(i\pi) = -1\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(\sin\) and \(\cos\) functions

Considerations of the triangle whose vertices are \[z_1 = 0,\qquad z_2 = \gamma(\theta), \qquad z_3 = C(\theta)\] show that \(\cos(\theta) = C(\theta)\) and \(\sin(\theta) = S(\theta)\). \[\begin{aligned} \sin x = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^{k}x^{2k+1}}{(2k+1)!},\qquad \text{ and } \qquad \cos x = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^kx^{2k}}{(2k)!}. \end{aligned}\]

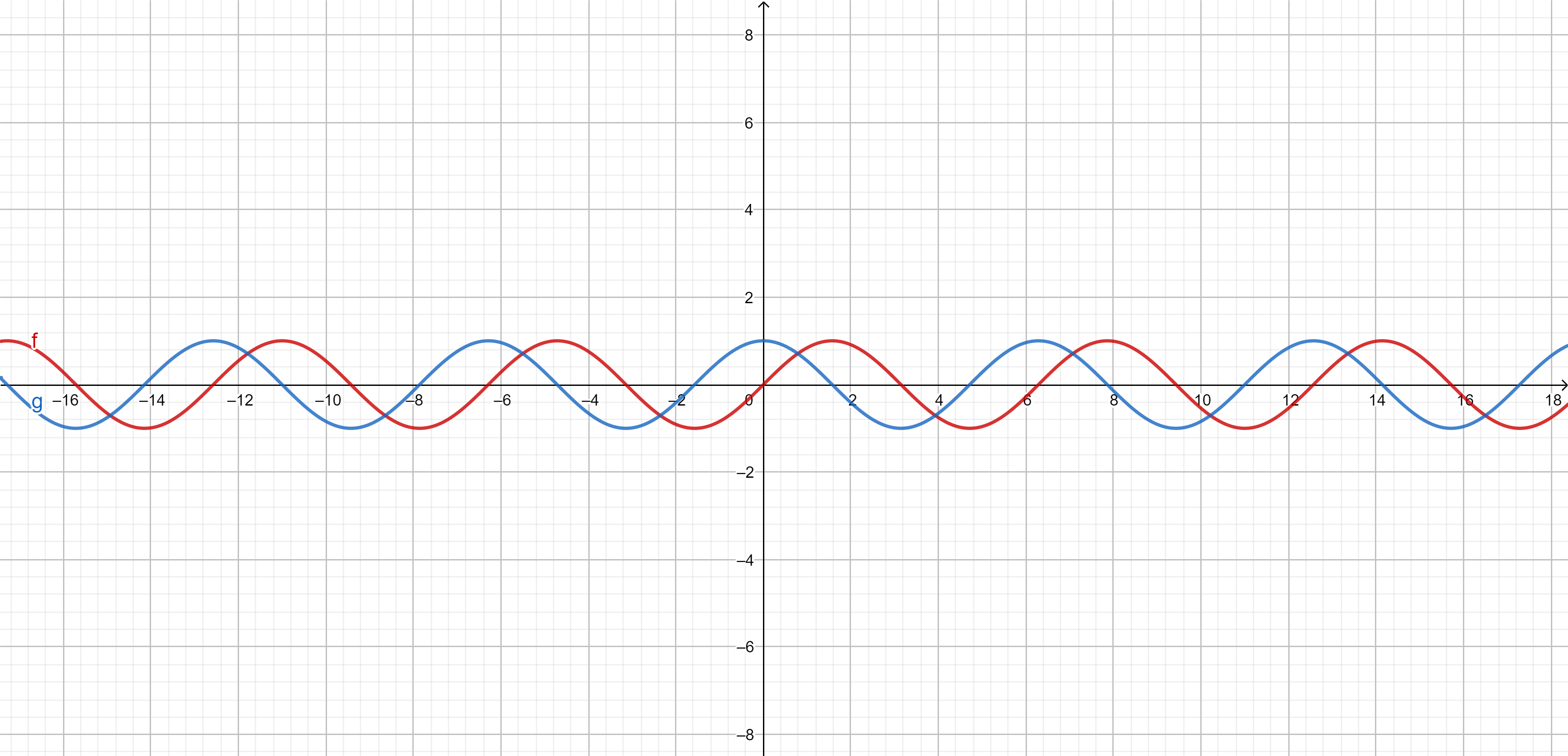

Graphs of \({\color{red}\sin(x)}\) and \({\color{blue}\cos(x)}\)

Now we can sketch the graphs of \({\color{red}\sin(x)}\) and \({\color{blue}\cos(x)}\):

Remark

Remark.

The curve \(\gamma(t) = E(it)\), with \((0 \leq t \leq 2\pi\), is a simple closed curve whose range is the unit circle in the plane.

Since \(\gamma'(t) = iE(it)\), the length of \(\gamma\) as we shall see soon is \[\int_0^{2\pi} |\gamma'(t)| dt = 2 \pi.\]

This is of course the expected result of the circumference of a circle of radius 1.

In the same way we see that the point \(\gamma(t)\) describes a circular arc length \(t_0\) as \(t\) increases from \(0\) to \(t_0\).

Limit \(\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}\)

Theorem. We have \[\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}=1.\]

Proof. We have \[\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sin(h)-\sin(0)}{h}=\sin'(0)=\cos(0)=1.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Taylor’s theorem

Taylor’s theorem

Taylor’s theorem. Suppose \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\), \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), \(f^{(n-1)}\) is continuous on \([a,b]\), and \(f^{(n)}(t)\) exists for every \(t \in (a,b)\). Let \(\alpha,\beta \in [a,b]\) be distinct and define \[{\color{red}P(t)=\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\frac{f^{(k)}(\alpha)}{k!}(t-\alpha)^k}.\]

then there exists a point \(x \in (\alpha,\beta)\) such that \[\qquad \qquad \qquad f(\beta)=P(\beta)+\frac{f^{(n)(x)}}{n!}(\beta-\alpha)^n\qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{purple}(*)}\]

Remark. For \(n=1\) this is just the mean–value theorem. In general, the theorem says that \(f\) can be approximated by a polynomial of degree \(n-1\) and that (*) allows us to estimate the error term if we know bounds on \(|f^{(n)}(x)|\).

Proof. Let \(M\) be a number such that \[f(\beta)=P(\beta)+M(\beta-\alpha)^n.\] For \(a \leq t \leq b\) set

\[g(t)=f(t)-P(t)-M(t-\alpha)^n.\]

We have to show \({\color{blue}n!M=f^{(n)}(x)}\) for some \(x \in (\alpha,\beta)\).

Since \[P(t)=\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\frac{f^{(k)}(\alpha)}{k!}(t-\alpha)^k\] we have that \(P^{(n)}(t)=0\). Thus \[g^{(n)}(t)=f^{(n)}(t)-n!M \quad \text{ for }\quad t \in (\alpha,\beta)\] (since \((x^n)^{(n)}=n!\)).

The proof will be completed if we show that \({\color{red}g^{(n)}(x)=0}\) for some \(x \in (\alpha,\beta)\). Since \(P^{(k)}(\alpha)=f^{(k)}(\alpha)\) for \(k=0,1,2,\ldots,n-1\), hence we have \[{\color{brown}g(\alpha)=g'(\alpha)=\ldots=g^{(n-1)}(\alpha)=0}.\] Our choice of \(M\) shows that \({\color{brown}g(\beta)=0}\).

Hence by the mean-value theorem \[g'(x_1)=0\quad \text{ for some }\quad x_1 \in (\alpha,\beta)\] since \(0=g(\alpha)-g(\beta)=(\beta-\alpha)g'(x_1)\).

Using that \(g'(\alpha)=0\) we continue and obtain \[0=g'(x_1)-g'(\alpha)=(x_1-\alpha)g''(x_2) \quad \text{ for some }\quad \alpha<x_2<x_1.\] Thus \(g''(x_2)=0\).

Repeating the previous arguments, after \(n\) steps we obtain \[{\color{red}g^{(n)}(x_n)=0}\quad \text{ for some }\quad \alpha<x_n<x_{n-1}<\ldots<x_1<\beta.\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem

Theorem (Taylor’s expansion formula). Suppose that \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) is \(n\)-times continuously differentiable on \([a,b]\) and \(f^{(n+1)}\) exists in the open interval \((a,b)\). For any \(x,x_0 \in [a,b]\) and \(p>0\) there exists \(\theta \in (0,1)\) such that \[{\color{blue}f(x)=\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{f^{(k)}(x_0)}{k!}(x-x_0)^k+r_n(x),}\] where \(r_n(x)\) is the Schlömlich–Roche remainder function defined by \[{\color{teal}r_n(x)=\frac{f^{(n+1)}(x_0+\theta(x-x_0))}{n!p}(1-\theta)^{n+1-p}(x-x_0)^{n+1}}.\]

For \(x,x_0 \in [a,b]\) set \[r_n(x)=f(x)-\sum_{k=0}^n\frac{f^{(k)}(x_0)}{k!}(x-x_0)^k.\]

Wlog we may assume that \(x>x_0\). For \(z\in [x_0,x]\) define \[\phi(z)=f(x)-\sum_{k=0}^n\frac{f^{(k)}(z)}{k!}(x-z)^k.\]

We have \(\phi(x_0)=r_n(x)\) and \(\phi(x)=0\), and \(\phi'\) exists in \((x_0,x)\) and

\[\phi'(z)=-\frac{f^{(n+1)}(z)}{n!}(x-z)^{n}.\]

Indeed, by the telescoping we obtain \[\begin{aligned} \phi'(z)&=-\left(\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{f^{(k)}(z)}{k!}(x-z)^k\right)' \\&=-\sum_{k=0}^n \left({\color{red}\frac{f^{(k+1)}(z)}{k!}(x-z)^k}-{\color{blue}\frac{f^{(k)}(z)}{k!}k(x-z)^{k-1}}\right) \\&={\color{red}\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{f^{(k)}(z)}{(k-1)!}(x-z)^{k-1}}-{\color{blue}\sum_{k=0}^n\frac{f^{(k+1)}(z)}{k!}(x-z)^{k}} \\&=-\frac{f^{(n+1)}(z)}{n!}(x-z)^{n}. \end{aligned}\]

Let \(\psi(z)=(x-z)^p\), then \(\psi\) is continuous on \([x_0,x]\) with non-vanishing derivative on \((x_0,x)\).

By the mean-value theorem \[\frac{\phi(x)-\phi(x_0)}{\psi(x)-\psi(x_0) }=\frac{\phi'(c)}{\psi'(c)} \quad \text{ for some }\quad c \in (x_0,x ).\]

Thus, setting \({\color{brown}c=x_0+\theta(x-x_0)}\), \[\begin{aligned} r_n(x)&=\underbrace{\phi(x_0)}_{{\color{red}=r_n(x)}}-\underbrace{\phi(x)}_{{\color{red}=0}}=-(\psi(x)-\psi(x_0))\frac{\phi'(c)}{\psi'(c)} \\&=\frac{f^{(n+1)}(c)}{n!}(x-c)^n\frac{-(x-x_0)^p}{-p(x-c)^{p-1}}= \\&={\color{brown}\frac{f^{(n+1)}(x_0+\theta(x-x_0))}{pn!}(1-\theta)^{n+1-p}(x-x_0)^{n+1}}.\end{aligned}\qquad\blacksquare\]

Corollary

Under the assumptions of the previous theorem.

Lagrange remainder. If \(p=n+1\) we obtain the Taylor formula with the Lagrange remainder: \[{\color{red}r_n(x)=\frac{f^{(n+1)}(x_0+\theta(x-x_0))}{(n+1)!}(x-x_0)^{n+1}}.\]

Cauchy remainder. If \(p=1\) we obtain the Taylor formula with the Cauchy remainder: \[{\color{blue}r_n(x)=\frac{f^{(n+1)}(x_0+\theta(x-x_0))}{n!}(1-\theta)^n(x-x_0)^{n+1}}.\]

Power series expansions

Power series expansion for the logarithm

Theorem. For \(|x|<1\) we have \[{\color{teal}\log(1+x)=\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^{k+1}}{k}x^k.}\]

Proof. Note that \((\log(x+1))'=\frac{1}{x+1}\) and \[\begin{gathered} (\log(x+1))''=\left(\frac{1}{x+1}\right)'=-\frac{1}{(1+x)^2},\\ (\log(x+1))'''=\left(=-\frac{1}{(1+x)^2}\right)=\frac{2}{(1+x)^3},\\ (\log(x+1))^{(4)}=\left(\frac{2}{(1+x)^3}\right)'=-\frac{6}{(1+x)^4}=-\frac{3!}{(1+x)^4}. \end{gathered}\]

Inductively, we have \[{\color{blue}(\log(1+x))^{(n)}=(-1)^{n+1}\frac{(n-1)!}{(x+1)^n}}.\]

We use the Taylor expansion formula at \(x_0=0\) then \[\log(1+x)=\sum_{k=0}^n\frac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}x^k+r_n(x)=\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{(-1)^{k+1}}{k}x^k+r_n(x),\] since \[\begin{aligned} f^{(0)}(0)&=\log(1)=0,\\ f^{(k)}(0)&=(-1)^{k+1}(k-1)!. \end{aligned}\]

If \(0 \leq x <1\) we use Lagrange’s reminder. Then for some \(0<\theta<1\), \[|r_n(x)|=\left|\frac{f^{(n)}(\theta x)}{(n+1)!}x^{n+1}\right|=\frac{n!}{(n+1)!(1+\theta x)^n}x^{n+1} \leq \frac{1}{n+1} \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0.\]

If \(-1<x<0\) we use Cauchy’s remainder. Then for some \(0<\theta<1\), \[\begin{aligned} |r_n(x)|&=\left|\frac{f^{(n+1)}(x_0+\theta(x-x_0))}{n!}(1-\theta)^{n}(x-x_0)^{n+1}\right|\\ &=\left|\frac{n!}{n!(1+\theta x)^{n+1}}(1-\theta)^n x^{n+1}\right|. \end{aligned}\]

Since \(-1<\theta x<0\), then \(-\theta<\theta x\), so \(1-\theta<1+\theta x\), hence \[|r_n(x)| \leq \frac{(1-\theta)^n}{(1+\theta x)^{n+1}}|x|^{n+1} \leq \frac{(1-\theta)^n}{(1-\theta )^{n+1}}|x|^{n+1}=\frac{|x|^{n+1}}{1-\theta} \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0\] since \(|x|^n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0\) when \(|x|<1\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Newton’s binomial formula

Theorem. If \(\alpha \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \mathbb{N}\) and \(|x|<1\) then \[(1+x)^{\alpha}=1+\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\underbrace{\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (\alpha-n+1)}{n!}}_{{\color{red}{\alpha \choose n}}}x^n.\] This is called Newton’s binomial formula.

Recall. For \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) we have \[{n \choose k}=\frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}=\frac{n(n-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (n-k+1)}{k!}.\]

Proof. Let let \(f(x)=(1+x)^{\alpha}\) and note that \[f^{(n)}(x)=\alpha(\alpha-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (\alpha-n+1)x^{\alpha-n}.\]

Suppose first that \(0<x<1\).

Using the Lagrange remainder formula we have \[r_n(x)=\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (\alpha-n)}{(n+1)!}x^{n+1}(1+x\theta)^{\alpha-n+1}.\]

Claim. For \(|x|<1\) we have \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (\alpha-n)}{(n+1)!}x^{n+1}=0.\]

To prove the claim it suffices to use the following fact:

Fact. \[{\color{red}\lim_{n \to \infty}\left|\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}\right|=q<1\quad \Longrightarrow\quad \lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=0}\]

with \(a_n=\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (\alpha-n)}{(n+1)!}x^{n+1}\). Then \[\begin{gathered} \left|\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}\right|= \left|\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (\alpha-n-1)x^{n+2}}{(n+2)!} \frac{(n+1)!}{\alpha(\alpha-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (\alpha-n+1)x^{n+1}}\right| \\ =\left|\frac{\alpha-n-1}{n+2}x \right| \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ |x|<1. \end{gathered}\]

Thus \(r_n(x) \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0\) if we show that \((1+\theta x)^{\alpha-n-1}\) is bounded.

Indeed, assuming that \(0<x<1\) we see \[(1+\theta x)^{-n} \leq 1,\]

For \(\alpha \geq 0\) we have \[1 \leq (1+\theta x)^{\alpha} \leq (1+x)^{\alpha} \leq 2^{\alpha},\]

For \(\alpha<0\) we have \[2^{\alpha} \leq (1+x)^{\alpha} \leq (1+x\theta)^{\alpha} \leq 1\]

Gathering all together we conclude that \((1+\theta x)^{\alpha-n-1}\) as desired.

Now we assume that \(-1<x<0\). Using the Cauchy remainder formula we have \[r_n(x)=\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)\cdot \ldots \cdot (\alpha-n)}{(n+1)!}x^{n+1}(1-\theta)^n(1+\theta x)^{\alpha-n-1}.\]

As before we show that \((1-\theta)(1+\theta x)^{\alpha-n-1}\) is bounded.

Since \(-1<x<0\) then \(1+\theta x>1-\theta\) and consequently \[(1-\theta)^n \leq (1-\theta)^n(1+\theta x)^{-n}=\frac{(1-\theta)^n}{(1+\theta x)^n}<1.\]

For \(\alpha \leq 1\) we have \[1 \leq (1+x\theta)^{\alpha-1} \leq (1+x)^{\alpha-1}.\]

For \(\alpha \geq 1\) we have \[(1+x)^{\alpha-1} \leq (1+\theta x)^{\alpha-1} \leq 1\] and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

A function which does not have power series representation

Let

\[f(x)=\begin{cases} e^{-\frac{1}{x^2}} &\text{ if }x \neq 0, \\ 0 &\text{ if }x=0. \end{cases}\].

It is not difficult to see that \(f\) is infinitely many times differentiable for any \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Moreover, \[f^{(n)}(0)=0 \quad \text{ for any }\quad n \geq 0\] and \(f(x) \neq 0\).

Thus we see \[0 \neq f(x) \neq \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\frac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}x^k=0.\]

Applications of Calculus

Bernoulli’s inequality: general form

Bernoulli’s inequality: general form. For \(x>-1\) and \(x \neq 0\) we have

\((1+x)^{\alpha}>1+\alpha x\) if \(\alpha>1\) or \(\alpha<0\),

\((1+x)^{\alpha}<1+\alpha x\) if \(0<\alpha<1\).

Proof. Applying Taylor’s formula with the Lagrange remainder for \(f(x)=(1+x)^{\alpha}\) we obtain \[{\color{blue}(1+x)^{\alpha}=1+\alpha x+\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)(1+\theta x)^{\alpha-2}}{2}x^2}.\]

For \(\alpha>1\) or \(\alpha<0\) we have \[\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)(1+\theta x)^{\alpha-2}}{2}>0.\]

For \(0<\alpha<1\) we have \[\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)(1+\theta x)^{\alpha-2}}{2}<0.\]

Consequently, for \(\alpha>1\) or \(\alpha<0\) we obtain \[1+\alpha x+\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)(1+\theta x)^{\alpha-2}}{2}x^2>1+x\alpha.\]

Similarly, for \(0<\alpha<1\), we obtain \[1+\alpha x+\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)(1+\theta x)^{\alpha-2}}{2}x^2>1+x\alpha.\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$