22. Riemann Integrals PDF

Partitions

Partition. Let \([a, b]\) be a given interval. By a partition \(P\) of \([a, b]\) we mean a finite set of points \[a=x_0 \leq x_1 \leq \ldots \leq x_{n-1} \leq x_n=b.\]

Example 1. If \([a,b]=[0,1]\), then \(\{0,\frac{1}{2},1\}\) is a partition.

Example 2. If \([a,b]=[0,1]\), then \[\left\{\frac{k}{n}\;:\;k=0,1,\ldots,n \right\}\] is a partition for every \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Upper and lower Riemann sums

Suppose \(f:[a,b]\to \mathbb R\) is a bounded function. Corresponding to each partition \(P\) of \([a, b]\) we put \[\begin{gathered} m_i=\inf_{x \in [x_{i-1},x_i]}f(x), \quad \text{ and } \quad M_i=\sup_{x \in [x_{i-1},x_i]}f(x),\\ \Delta x_i=x_{i}-x_{i-1}. \end{gathered}\]

Upper and lower Riemann sums. We define \[U(P,f)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}M_i\Delta x_i,\] \[L(P,f)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}m_i\Delta x_i.\]

We always have that \(L(P,f)\le U(P,f)\).

Examples

Example 1. If \(f(x)=x\) and \(P=\{0,\frac{1}{2},1\}\), then \[\begin{aligned} U(P,f)=\frac{1}{2}\cdot \frac{1}{2}+1 \cdot \frac{1}{2}=\frac{3}{4}, \quad \text{ and } \quad L(f,L)=0 \cdot \frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2}=\frac{1}{4}. \end{aligned}\]

Example 2. If \(f(x)=x^2\) and \[P=\left\{\frac{k}{n}\;:\; k=0,1,\ldots,n\right\},\] then \[U(P,f)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\frac{1}{n}\left(\frac{{\color{red}i}}{n}\right)^2, \quad \text{ and } \quad L(P,f)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\frac{1}{n}\left(\frac{{\color{blue}i-1}}{n}\right)^2.\]

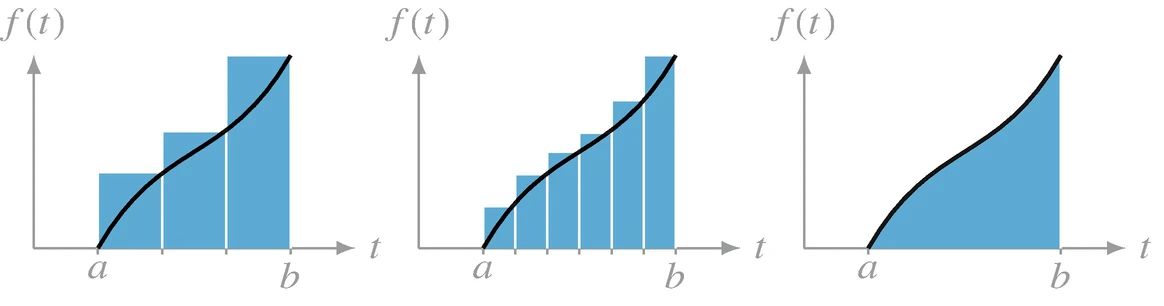

Riemann sums - geometric interpretation

Upper and lower Riemann integral

Upper and lower Riemann integral. We define the upper and lower Riemann integrals of \(f\) over \([a, b]\) to be \[\begin{aligned} \underline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx=\sup_P L(P,f), \quad \text{ and } \quad \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx=\inf_P U(P,f), \end{aligned}\] where the inf and the sup are taken over all partitions \(P\) of \([a,b]\).

Riemann integral of \(f\) over \([a, b]\). If the upper and lower integrals are equal, we say that \(f:[a, b]\to \mathbb R\) is Riemann integrable on \([a, b]\), we write \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\) and we denote the common value (which is called Riemann integral of \(f\) over \([a, b]\)) by \[\int_a^b f(x)\,dx= \underline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx= \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx.\]

Riemann integral is well-defined

Fact. The upper and lower integrals are defined for every bounded function.

Proof. Let \[\begin{aligned} m &=\inf_{x \in [a,b]} f(x),\\ M& =\sup_{x \in [a,b]}f(x). \end{aligned}\] Then \[m \leq f(x) \leq M \quad \text{ for all }\quad x \in [a,b].\] Therefore \[m(b-a) \leq L(P,f) \leq U(P,f) \leq M(b-a)\] for every partition \(P\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Question of the integrability of \(f\)

Example. There is a bounded function \(f\) which is not integrable.

Proof. Let us define \(f\) on \([0,1]\) to be \[f(x)=\begin{cases} 1 \text{ if }x \in \mathbb{Q},\\ 0 \text{ if }x\not\in \mathbb{Q}. \end{cases}\] Let us recall

Fact (*). In any interval \([c,d]\) such that \(c<d\) there is a rational and irrational number.

By the fact \({\color{purple}(*)}\), for every partition \(P\) of \([0, 1]\), we have

\[U(P,f)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}M_i\Delta x_i=\sum_{i=1}^n1\cdot \Delta x_i =1,\] \[L(P,f)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}m_i\Delta x_i=\sum_{i=1}^n 0\cdot \Delta x_i=0.\]

Therefore

\[\underline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx=\sup_P L(P,f)=0, \quad \text{ and } \quad \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx=\inf_P U(P,f)=1.\]

Hence \({\color{red}\underline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx \neq \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx}\) and \(f\) is not integrable.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Refinements

Refinement. We say that the partition \(P^{*}\) is a refinement of \(P\) if \(P^{*} \supseteq P\).

Common refinement. Given two partitions, \({\color{red}P_1}\) and \({\color{blue}P_2}\),we say that \(P^{*}\) is their common refinement if \[P^{*}={\color{red}P_1} \cup {\color{blue}P_2}.\]

Example. If \([a,b]=[0,2]\) and \(P_1=\{0,\frac{1}{2},1,2\}\), \(P_2=\{0,\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{2},\frac{3}{2},2\}\) are partitions, then their common refinement is \[P^{*}=\left\{0,\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{2},1,\frac{3}{2},2\right\}.\]

Theorem

Theorem. If \(P^*\) is a refinement of \(P\), then \[\begin{aligned} \color{red}L(P,f) &\color{red}\leq L(P^{*},f),\\ \color{blue}U(P^{*},f) &\color{blue}\leq U(P,f). \end{aligned}\]

Proof. We prove the first statement.

Suppose first that \(P^{*}\) contains just one point more than \(P\). Let this extra point be \(x^{*}\), and suppose \[x_{i-1} \leq x^{*} \leq x_i \quad \text{ for some }\quad i \in \{1,2,\ldots,n\}.\]

Let \[\begin{gathered} m_i=\inf_{x \in [x_{i-1},x_i]}f(x),\\ w_1=\inf_{x \in {\color{red}[x_{i-1},x^{*}]}}f(x), \quad \text{ and } \quad w_2=\inf_{x \in {\color{blue}[x^{*},x_i]}}f(x) \end{gathered}\]

Then \(w_1\ge m_i\) and \(w_2\ge m_i\) and consequently \[\begin{gathered} L(P^{*},f)-L(P,f)={\color{red}w_1(x^{*}-x_{i-1})}+{\color{blue}w_2(x_i-x^*)} -{\color{purple}m_i(x_i-x_{i-1})}\\ ={(w_1-m_i)(x^{*}-x_{i-1})}+{(w_2-m_i)(x_i-x^*)} \geq 0. \end{gathered}\]

Finally, if \(P^*\) contains \({\color{brown}k}\) points more than \(P\), we repeat this reasoning \({\color{brown}k}\) times. The proof of the second statement is analogous.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Claim (*). For two partitions \(P_1, P_2\) of an interval \([a, b]\) one has \[L(P_1,f) \leq U(P_2,f).\]

Proof. Let \(P^{*}=P_1\cup P_2\) be the common refinement of two partitions \(P_1\) and \(P_2\). By the previous theorem \[{\color{red}L(P_1,f) \leq L(P^*,f)} \leq {\color{blue}U(P^*,f) \leq U(P_2,f)}.\]

Theorem. For any bounded function \(f:[a,b]\to \mathbb R\) we have \[\underline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx \leq \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx.\]

Proof. By the Claim (*) for two partitions \(P_1, P_2\) of an interval \([a, b]\) one has \[L(P_1,f) \leq U(P_2,f).\] Then \[\underline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx=\sup_{P_1} L(P_1,f)\le \inf_{P_2} U(P_2,f)= \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx,\] This completes the proof of the theorem.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem. A function \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\) if and only if the following condition (\(\mathcal R\)) holds:

For every \(\varepsilon>0\) there is a partition \(P\) of \([a, b]\) such that \[\begin{aligned} \qquad\qquad \qquad U(P,f)-L(P,f)<\varepsilon. \qquad\qquad \qquad {\color{purple} (\mathcal R)} \end{aligned}\]

Proof. By the previous theorem, for every partition \(P\) we have \[L(P,f) \leq \underline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx\leq \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx \leq U(P,f).\] Thus the condition (\(\mathcal R\)) implies \[0\le \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx-\underline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx\le U(P,f)-L(P,f)<\varepsilon.\] Since \(\varepsilon>0\) is arbitrary \(\overline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx=\underline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx\), hence \(f \in \mathcal{R}(\alpha)\).

Conversely, suppose that \(f \in \mathcal{R}(\alpha)\). Then for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there are partitions \({\color{red}P_1}\) and \({\color{blue}P_2}\) such that \[\begin{aligned} {\color{red}\underline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx-L(P_1,f)<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}} \quad \text{ and } \quad {\color{blue}U(P_2,f)-\overline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}}. \end{aligned}\]

We choose \(P\) to be the common refinement of \({\color{red}P_1}\) and \({\color{blue}P_2}\). Then \[\begin{gathered} U(P,f) \leq U(P_2,f)\\ \leq \overline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}= {\int_a^b}f(x)dx+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}= \underline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\\ \leq L(P_1,f)+\varepsilon \leq L(P,f)+\varepsilon. \end{gathered}\] This proves condition (\(\mathcal R\)) and completes the proof of the theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem (**). If condition (\(\mathcal R\)) holds for \(P=\{x_0,\ldots,x_n\}\) and if \(s_i,t_i\) are arbitrary points in \([x_{i-1},x_i]\), then \[\sum_{i=1}^{n}|f(s_i)-f(t_i)|\Delta x_i<\varepsilon.\]

Proof. Note that \(f(s_i),f(t_i)\) lies in \([m_i,M_i]\), hence by the triangle inequality \[|f(t_i)-f(s_i)| \leq \underbrace{M_i-m_i}_{\text{length}}.\] Hence \[\begin{aligned} &\sum_{i=1}^{n}|f(s_i)-f(t_i)|\Delta x_i \leq \sum_{i=1}^{n}(M_i-m_i)\Delta x_i =\overline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx -\underline{\int_a^b}f(x)dx <\varepsilon. \end{aligned}\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem. If \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\) and the hypotheses of \({\color{brown}(**)}\) hold, then \[\left|\sum_{i=1}^nf(t_i)\Delta x_i-\int_a^bf(x)\,dx\right|<\varepsilon.\]

Proof. It is enough to note that \[\begin{aligned} L(P,f) &\leq \sum_{i=1}^nf(t_i)\Delta x_i \leq U(P,f),\\ L(P,f) &\leq \int_a^b f(x)\;dx \leq U(P,f).\quad\end{aligned}\qquad\blacksquare\]

Riemann integrability for continuous functions

Theorem. If \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b]\) then \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a,b])\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Choose \(\eta>0\) such that \(\eta(b-a)<\varepsilon.\) Recall that if \(f\) is continuous on \([a,b]\), then it is also uniformly continuous.

Hence, there is \(\delta>0\) such that \(|f(x)-f(t)|<\eta\) if \(|t-x|<\delta.\)

In particular, that means that \({\color{red}M_i-m_i<\eta}\) for every partition such that \(\Delta x_i<\delta\).

Hence, \[\begin{aligned} U(P,f)-L(P,f)=\sum_{i=1}^n(M_i-m_i)\Delta x_i \leq \eta \sum_{i=1}^n \Delta x_i=\eta(b-a)<\varepsilon. \end{aligned}\]

The proof is completed. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Riemann integrability for monotonic functions

Theorem. If \(f:[a, b]\to \mathbb R\) is monotonic, then \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. For \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) choose a partition \(P\) such that \({\color{red}\Delta x_i=\frac{b-a}{n}}\). We suppose that \(f\) is monotonically increasing. Then \[{\color{blue}M_i-m_i=f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1}).}\] Hence, if \(n\) is taken large enough, we obtain \[\begin{aligned} U(P,f)-L(P,f)&=\sum_{i=1}^n(M_i-m_i)\Delta x_i \\ & ={\color{red}\frac{b-a}{n}}\sum_{i=1}^n{\color{blue}f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1})}=\frac{b-a}{n}(f(b)-f(a))<\varepsilon, \end{aligned}\] and we are done, the proof is analogous in the other case.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example

Example 1. Let \[f(x)=\begin{cases} x &\text{ for }x \in [0,1],\\ x^2+5 &\text{ for }x\in (1,2], \\ x^3+9 &\text{ for }x\in(3,4]. \end{cases}\] Prove that \(f\) is Riemann integrable on \([0,4]\).

Solution. \(f\) is increasing, so \(f\) is Riemann integrable by the previous theorem.

Riemann integrability for discontinues functions

Theorem. Suppose \(f: [a, b]\to \mathbb R\) is bounded and has only finitely many points of discontinuity on \([a, b]\). Then \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Put \({\color{red}M=\sup_{x\in[a, b]} |f(x)|}\), let \(E\) be the set of points at which \(f\) is discontinuous.

Since \(E\) is finite, \(E\) can be covered by finitely many disjoint intervals \([u_i,v_i] \subseteq [a,b]\) such that \(v_i-u_i<\varepsilon\).

Furthermore, we can place these intervals in such a way that every point of \(E \cap (a,b)\) lies in the interior of some \([u_i,v_i]\).

Remove the segments \((u_i,v_i)\) from \([a,b]\).

The remaining set K is compact. Hence \(f\) is uniformly continuous on \(K\), and there exists \(\delta>0\) such that \[|f(s)-f(t)|<\varepsilon \quad \text{ if }\quad s,t \in K \quad \text{ and }\quad |s-t|<\delta.\]

Now form a partition \(P\) of \([a, b]\) as follows:

Note that \(M_i-m_i \leq 2M\) for all \(i\), and by the uniform continuity of \(f\) we also have that \(M_i-m_i\le \varepsilon\) unless \(x_{i-1}\) is one of the \(u_j\).

Hence

\[U(P,f)-L(P,f) \leq {\color{red}\varepsilon(b-a)}+{\color{blue}2M\varepsilon}.\]

Since \(\varepsilon>0\) is arbitrary, the proof is finished. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Exercise

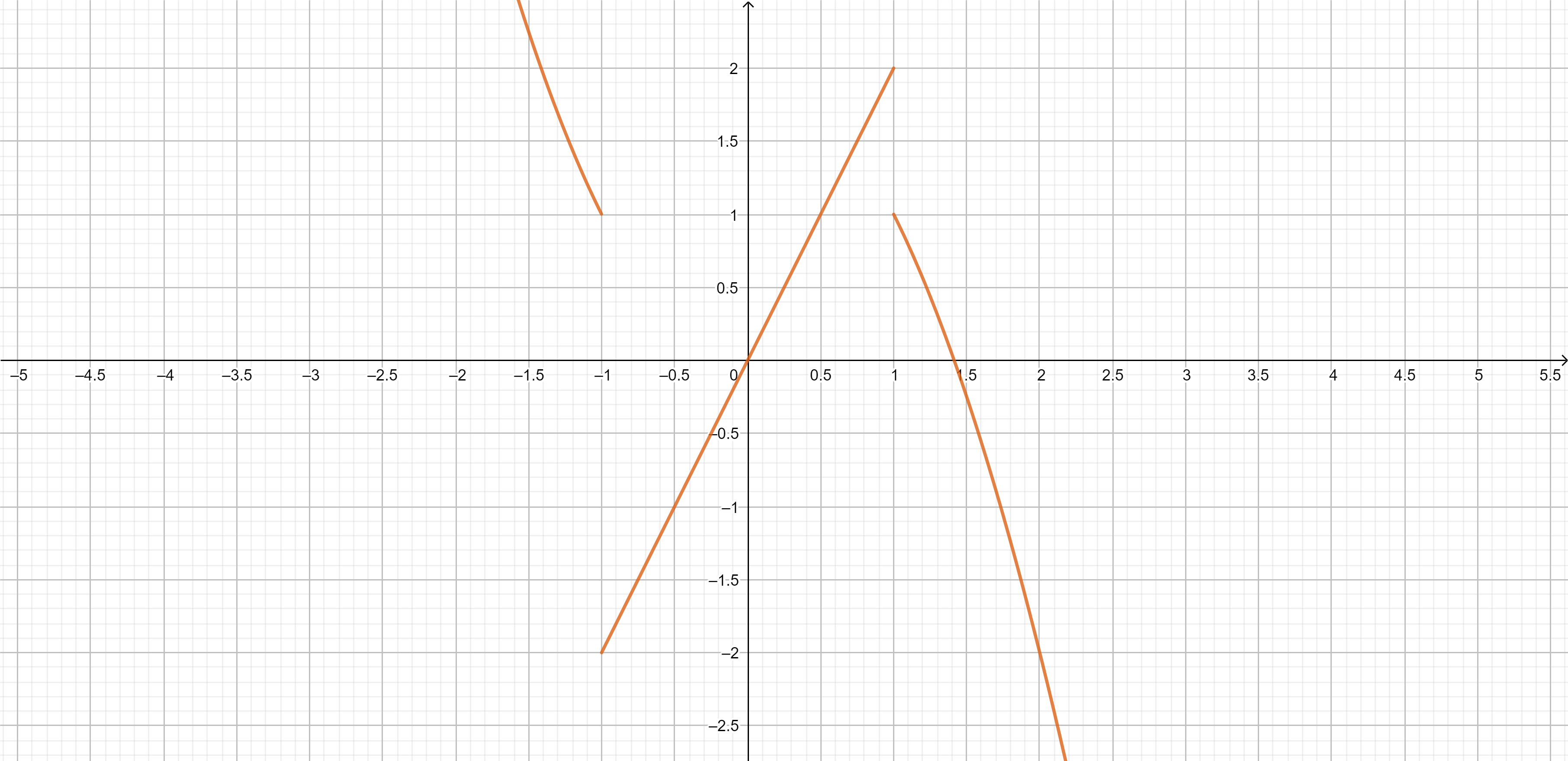

Exercise. Prove that the function given by \[f(x)=\begin{cases} x^2& \text{ if }x \in [-3,-1],\\ 2x &\text{ if }x \in (-1,1],\\ -x^2+2 &\text{ if }x\in (1,3] \end{cases}\] is Riemann integrable.

Exercise - solution

The function is continuous except \(-1\), \(1\). Hence, by the previous theorem, it is Riemann integrable.

Linearity of Riemann integrals

Linearity of Riemann integrals. If \(f_1,f_2 \in \mathcal{R}([a,b])\) and \(c \in \mathbb{R}\), then \(f_1+f_2 \in \mathcal{R}([a,b])\) and \[\int_a^b f_1(x)+f_2(x)\;dx=\int_a^b f_1(x)\;dx+\int_a^b f_2(x)\;dx,\] \[\int_a^b cf_1(x)(x)\;dx=c\int_a^b f_1(x)\;dx.\]

Proof. We only prove the first statement. The proof of the second statement is similar.

If \(f=f_1+f_2\), then for any partition \(P\) we have \[\begin{aligned} L(P,f_1)+L(P,f_2) \leq L(P,f) \leq U(P,f) \leq U(P,f_1)+U(P,f_2). \quad {\color{purple}(*)} \end{aligned}\]

For a given \(\varepsilon>0\) there are partitions \(P_1, P_2\) such that \(U(P_j,f_j)-L(P_j,f_j)<\varepsilon\) for \(j=1,2.\)

Let \(P\) be the common refinement of \(P_1\) and \(P_2\). Together with \({\color{purple}(*)}\) this means that \(U(P,f)-L(P,f)<2\varepsilon,\) which proves \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\).

With the same \(P\) we have \[U(P,f_j) \leq \int_a^b f_j(x)\,dx+\varepsilon\]

Hence \({\color{purple}(*)}\) implies \[\int_a^b f(x)\,dx \leq U(P,f) \leq \int_a^b f_1(x)\,dx+\int_a^b f_2(x)\,dx+2\varepsilon.\]

Since \(\varepsilon>0\) we arbitrary, we have \[\int_a^bf(x)\,d\alpha(x) \leq \int_a^bf_1(x)\,d\alpha(x)+\int_a^bf_2(x)\,d\alpha(x).\]

If we replace \(f_1\) and \(f_2\) with \(-f_1\) and \(-f_2\) respectively, the inequality can be reversed, which proves the desired equality. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Properties of Riemann integrals

Properties of Riemann–Stieltjes integral. Assume \(f_1,f_2 \in \mathcal{R}([a,b])\).

If \(f_1 \leq f_2\), then \[\int_a^b f_1(x)\,dx \leq \int_a^b f_2(x)\,dx.\]

If \(a <c< b\) and \(f_1 \in \mathcal{R}([a,c])\) and \(f_1 \in \mathcal{R}([c,b])\), then \[\int_a^bf_1(x)\;dx=\int_a^cf_1(x)\;dx+\int_c^bf(x)\;dx.\]

Composition and product of Riemann integrable functions

Theorem (*). Suppose \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\), and \(m \leq f \leq M\), and \(\phi:[m,M]\to \mathbb R\) and \[{\color{blue}h(x)=\phi(f(x))}.\] Then \(h \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\). Prove it!

As a consequence of this theorem, we have the following facts:

Fact. Assume that \(f,g \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\). Then

\(fg \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\),

\(\left|\int_a^b f(x)\,dx\right| \leq \int_a^b |f(x)|\,dx\).

For the proof of (a), it is enough to use the following identity \[4fg=(f+g)^2-(f-g)^2,\] the fact that \(f+g\), \(f-g\) are integrable and Theorem \({\color{red}(*)}\) with \({\color{brown}\phi(t)=t^2}\).

For the proof of (b), choose \(c\in \mathbb R\) such that \[\left|\int_a^bf(x)\,dx\right|=c\int_a^b f(x)\,dx=\int_a^bcf(x)\,dx>0.\] then by Theorem \({\color{red}(*)}\) with \({\color{brown}\phi(t)=|t|}\) we obtain \[\left|\int_a^bf(x)\,dx\right| = c\int_a^b f(x)\,dx=\int_a^bcf(x)\,dx \leq \int_a^b|f(x)|\,dx.\quad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Change of variable formula

Theorem (change of variable formula). Suppose that \(\phi\) is a strictly increasing continuous function that maps an interval \([A, B]\) onto \([a, b]\) and \(\phi'\in \mathcal{R}([A, B])\). Suppose that \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a,b])\), then \(f\circ \phi \in \mathcal{R}([A,B])\) and \[{\color{blue}\int_a^b f(x)\,dx=\int_A^Bf(\phi(x)) \phi'(x)\,dx.}\]

Proof. To each partition \(Q=\{y_0, \ldots, y_n\}\) of \([a, b]\) corresponds a partition \(P=\{x_0,\ldots,x_n\}\) of \([A, B]\), so that \[{\color{brown}y_i=\phi(x_i)}.\] All partitions of \([A, B]\) are obtained in this way.

Let \(\varepsilon>0\). There is a partition \(P\) such that \(U(P,\phi')-L(P,\phi')<\varepsilon.\) The mean-value theorem furnishes points \(t_i \in (x_{i-1},x_i)\) such that \[{\color{blue}y_i-y_{i-1}=\phi(x_i)-\phi(x_{i-1})=\phi'(t_i)\Delta x_i.}\]

Let \(M=\sup_{x\in[a, b]} |f(x)|\). Then, if \(s_i \in [x_{i-1},x_i]\), we have \[\sum_{i=1}^n |\phi'(s_i)-\phi'(t_i)|\Delta x_i<\varepsilon.\]

Hence, \[\sum_{i=1}^nf(s_i)\Delta y_i=\sum_{i=1}^n f(s_i)\phi'(t_i)\Delta x_i.\] \[\left|\sum_{i=1}^n f(s_i)\Delta y_i-\sum_{i=1}^n f(s_i)\phi'(s_i)\Delta x_i\right|<M\varepsilon.\]

In particular, \[\sum_{i=1}^n f(s_i)\Delta y_i \leq U(P,f\phi')+M\varepsilon.\]

The last inequality holds for all choices of \(P\) (consequently \(Q\)), hence \[U(Q,f) \leq U(P,f\phi')+M\varepsilon \quad \Longrightarrow\quad {\color{red}|U(Q,f) - U(P,f\phi')| \leq M\varepsilon}.\]

Hence \[\left|\overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx-\overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\phi'(x)\,dx\right|<M\varepsilon.\] Since \(\varepsilon>0\) was arbitrary, \[\overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\,dx=\overline{\int_a^b}f(x)\phi'(x)\,dx\]

The equality for lower integral follows the same way.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example

Example. We note that \[\int_0^2 2x\cdot e^{-x^2}\,dx=\int_0^4 e^{-x}\,dx.\]

Taking \(\phi:[0, 2]\to [0, 4]\) given by \(\phi(x)=x^2\), and \(f(x)=e^{-x}\), we see that \[\int_0^2 \underbrace{(2x)}_{\phi'(x)}\cdot \underbrace{e^{-x^2}}_{f(\phi(x))}\,dx=\int_0^4 e^{-x}\,dx.\]

Integration and differentiation

Integration and differentiation. Let \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\) and \[{\color{red}F(x)=\int_a^xf(y)\,dy} \quad \text{ for } \quad x\in[a, b],\] then \(F\) is continuous on \([a, b]\). Furthermore, if f is continuous at \(x_0\in [a, b]\), then \(F\) is differentiable at \(x_0\), and \[{\color{blue}F'(x_0)=f(x_0).}\]

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\). Suppose that \(|f(x)| \leq M\). Then for all \(a \leq x_1 \leq x_2 \leq b\) we have \[|F(x_1)-F(x_2)| \leq \int_{x_1}^{x_2}|f(y)|\,dy \leq M(x_2-x_1).\] Therefore, \(|F(x_1)-F(x_2)| <\varepsilon\) if \(|x_1-x_2|<\frac{\varepsilon}{M}\). Hence \(F\) is continuous.

Now suppose \(f\) is continuous at \(x_0\). Given \(\varepsilon>0\), choose \(\delta>0\) such that \[|f(x_0)-f(t)|<\varepsilon \quad \text{ if } \quad |x_0-t|<\delta.\] Hence, if \[x_0-\delta \leq s \leq x_0 \leq t \leq x_0+\delta,\] then \[\begin{aligned} \left|\frac{F(t)-F(s)}{t-s}-f(x_0)\right|& =\left|\frac{F(t)-F(s)}{t-s}-{\color{blue}\frac{1}{t-s}\int_s^tf(x_0)\,dy}\right|\\ &=\left|\frac{1}{t-s}\int_s^t(f(y)-f(x_0))\,dy\right| \leq \frac{t-s}{t-s}\varepsilon=\varepsilon. \end{aligned}\] It follows that \(F'(x_0)=f(x_0)\) and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The fundamental theorem of calculus

The fundamental theorem of calculus. If \(f \in \mathcal{R}([a, b])\) and if there is a differentiable function \(F\) on \([a, b]\) such that \(F'=f\), then \[{\color{red}\int_a^b f(x)\,dx=F(b)-F(a)}.\]

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\). Choose a partition \(P\) such that \(U(P,f)-L(P,f)<\varepsilon\). The mean value theorem furnishes points \(t_i \in [x_{i-1},x_i]\) such that \(F(x_i)-F(x_{i-1})=f(t_i)\Delta x_i.\) Hence, \[\begin{aligned} \sum_{i=1}^n f(t_i)\Delta x_i=\sum_{i=1}^n(F(x_{i})-F(x_{i-1})) =F(b)-F(a). \end{aligned}\] This completes the proof, since \[\begin{aligned} \qquad \qquad\qquad \qquad \left|F(b)-F(a)-\int_a^b f(y)\,dy\right|<\varepsilon. \qquad \qquad\end{aligned}\qquad\blacksquare\]

Example

Example 1. Let \[h(x)=\int_0^x e^{-y^3}\sin(5y)\,dy.\] Calculate the derivative of \(h\).

Solution. By the previous theorem we have \[h'(x)=e^{-x^3}\sin(5x).\]

Example 2. Let \[h(x)=\int_{0}^{x^2} \frac{1}{y^2+e^{y^6}}\,dy.\] Calculate the derivative of \(h\).

Solution. Let us denote \[F(x)=\int_0^x \frac{1}{y^2+e^{y^6}}\,dy.\] By the previous theorem \[F'(x)=f(x)=\frac{1}{x^2+e^{x^6}}.\] Note that \(h(x)=F(x^2)\). Therefore, \[h'(x)=2xF'(x)=2xf(x)={\color{red}\frac{2x}{x^2+e^{x^6}}}.\]

Theorem (integration by parts)

Theorem (integration by parts). Suppose \(F\) and \(G\) are differentiable functions on \([a,b]\), and \(F'=f \in \mathcal{R}([a,b])\), and \(G'=g \in \mathcal{R}([a,b])\). Then \[\int_a^b F(x)g(x)\,dx=F(b)G(b)-F(a)G(a)-\int_a^b f(x)G(x)\,dx.\]

Proof. Let \[H(x)=F(x)G(x).\] By the chain rule, \[H'(x)=F(x)g(x)+f(x)G(x).\] Finally, we apply the previous theorem to \(H\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$