3. Least Upper Bounds and Greatest Lower Bounds; Fields and Ordered Fields; Axiom of Completeness PDF

Totally ordered sets \(\equiv\) linearly ordered sets

Total order \(\equiv\) linear order

One of the equivalent definitions of a total order reads as follows:

Definition.

A total order is a binary relation \(<\) on a set \(S\) which satisfies:

If \(x,y \in S\), then one and only one of the following is true:

\(x<y\),

\(y<x\) (equivalently \(x>y\)),

\(x=y\).

If \(x,y,z \in S\), \(x<y\) and \(y<z\), then \(x<z\).

Notation:

\(x \leq y\) means (\(x=y\) or \(x<y\)).

Equivalently, \(x \leq y\) is the negation of \(x>y\).

In Rudin’s book total order \(\equiv\) linear order is abbreviated to order.

Totally ordered sets \(\equiv\) linearly ordered sets

Definition. A totally ordered set (\(\equiv\) linearly ordered set) \((S, <)\) is the set \(S\) on which the order \(<\) is defined.

In Rudin’s book totally ordered set \(\equiv\) linearly ordered set is abbreviated to ordered set.

Example. The set of rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\) is ordered set if \(<\) is the usual order on numbers. We say that \(r<s\) for \(r, s\in\mathbb Q\) iff \(s-r>0\).

Supremum and infimum

Upper and lower bounds

Upper bound. Suppose that \(S\) is a totally ordered set and \(E \subseteq S\). If there is \(\beta \in S\) such that \[\alpha \leq \beta \qquad \text{for all} \qquad \alpha \in E,\] then \(E\) is bounded above and \(\beta\) is called the upper bound of \(E\).

Lower bound. Suppose that \(S\) is a totally ordered set and \(E \subseteq S\). If there is \(\beta \in S\) such that \[\beta \leq \alpha \qquad \text{for all} \qquad \alpha \in E,\] then \(E\) is bounded below and \(\beta\) is called the lower bound of \(E\).

Maximal/minimal and greatest/least elements

Greatest/maximal (least/minimal) elements. Suppose that \((S, <)\) is a totally ordered set. A greatest/maximal element of \(S\) is an element \(x \in S\) such that \[y \leq x \quad \text{for all}\quad y \in S.\] A least/minimal element of \(S\) is an element \(x \in S\) such that \[x \leq y \quad \text{for all}\quad y \in S.\]

Remark. In totally ordered sets in contrast to general partially ordered sets

the greatest and maximal elements are the same,

the least and minimal elements are the same.

\(\sup E\) \(\equiv\) supremum of \(E\)

\(\sup E\). Suppose that \(S\) is a totally ordered set, \(E \subset S\), and \(E\) is bounded from above. Suppose that there exists \(\alpha \in S\) with the following properties:

\(\alpha\) is a upper bound of \(E\),

if \(\gamma<\alpha\), then \(\gamma\) is not an upper bound of \(E\) (equivalently, there is \(x \in E\) such that \(\gamma<x \leq \alpha\)).

Then \(\alpha\) is called a least upper bound or supremum of \(E\). We write \[\alpha=\sup E.\]

\(\inf E\) \(\equiv\) infimum of \(E\)

\(\inf E\). Suppose that \(S\) is a totally ordered set, \(E \subset S\), and \(E\) is bounded from below. Suppose that there exists \(\alpha \in S\) with the following properties:

\(\alpha\) is a lower bound of \(E\),

if \(\gamma>\alpha\), then \(\gamma\) is not a lower bound of \(E\) (equivalently, there is \(x \in E\) such that \(\alpha \leq x <\gamma\)).

Then \(\alpha\) is called the greatest lower bound or infimum of \(E\). We write \[\alpha=\inf E.\]

Example

Example. Let \[E=\left\{\frac{1}{n} \colon n \in \mathbb{N}\right\}\subseteq \mathbb Q.\] Then \(\sup E=1\) and \(1 \in E\), but \(\inf E=0\) and \(0 \not\in E\).

Proof. Indeed, note that

\(\frac{1}{n}\le 1\) for all \(n\in\mathbb N\), and \(1=\frac{1}{n}\in E\) for \(n=1\), thus \(1=\sup E\).

\(\frac{1}{n}> 0\) for all \(n\in\mathbb N\). Thus \(0\) is the lower bound for \(E\), but \(0 \not\in E\).

By the the Archimedean property for the rational numbers we know that for every positive rational number \(x>0\) there exists \(n\in \mathbb N\) such that \(0<\frac{1}{n}<x\). Thus \(\inf E=0\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Find \(\sup E\) and \(\inf E\), where \[E=\left\{(-1)^n:n \in \mathbb{N}_0\right\}.\]

Solution. We have \((-1)^n=1\) for even \(n\) and \((-1)^n=-1\) for odd \(n\).

Hence \[E=\{-1,1\}.\]

Consequently \[\begin{aligned} \sup E&=\max E=1,\\ \inf E&=\min E=-1. \end{aligned}\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Find \(\sup E\) and \(\inf E\), where \[E=\left\{\frac{1}{n^2+1}: n \in \mathbb{N}_0\right\}\subseteq \mathbb Q.\]

Solution. Note that

\(\frac{1}{n^2+1} \leq \frac{1}{1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\), and \(1=\frac{1}{n^2+1}\in E\) for \(n=0\), hence \(1\) is the greatest element of \(E\) and we have \(\sup E=1\).

\(\frac{1}{n^2+1}>0\) for all \(n\in \mathbb{N}_0\). Thus \(0\) is the lower bound for \(E\), but \(0 \not\in E\).

By the the Archimedean property for the rational numbers we know that for every positive rational number \(x>0\) there exists \(n\in \mathbb N\) such that \(0<\frac{1}{n}<x\). Also \(n<n^2+1\) which implies \(0<\frac{1}{n^2+1}<\frac{1}{n}<x\). Hence \(\inf E=0\not\in E\).

Least–upper–bound property

Least–upper–bound property

Least–upper–bound property \(\equiv\) Axiom of completeness (AoC). A totally ordered set \(S\) is said to have least–upper–bound property (or satisfies the axiom of completeness (AoC)) if the supremum \(\sup E\) exists in \(S\) for all nonempty subsets \(E \subseteq S\) that are bounded above.

Example. Let \[A=\{p \in \mathbb{Q}\;:\;p>0,\; p^2<2\},\] \[B=\{p \in \mathbb{Q}\;:\;p>0,\; p^2>2\}.\] The set \(A\) is bounded from above. In fact, the upper bounds of \(A\) are exactly the members of \(B\). Since \(B\) contains no smallest member, it has no least upper bound in \(\mathbb{Q}\).

Hence \(\mathbb{Q}\) has no the least–upper–bound property.

Theorem

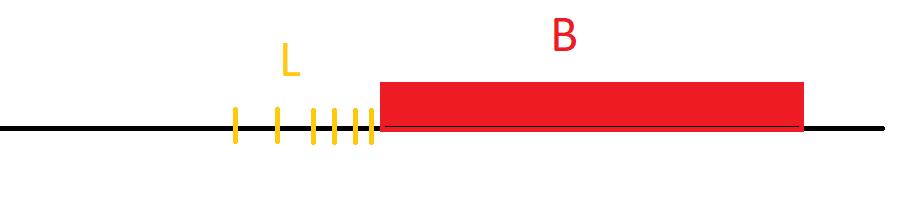

Theorem. Suppose that \(S\) is a totally ordered set with the least–upper–bound property. Let \(\varnothing\neq B \subseteq S\) be bounded below. Let \(L\) be the set of all lower bounds of \(B\). Then \(\alpha=\sup L\) exists in \(S\) and \(\alpha=\inf B\).

Proof. Let \[L=\{y \in S\colon y \leq x \text{ for all }x \in B\}.\]

We see that \(L \neq \varnothing\),

since \(B\) is bounded below. Every

\(x \in B\) is an upper bound of \(L\). Thus \(L\) is bounded above and consequently the

least–upper–bound property implies that \(\alpha=\sup L\) exists in \(S\).

We show that \(\alpha \in

L\). It suffices to prove that \(\alpha \leq x\) for all \(x \in B\). Suppose for a contradiction that

there is \(\gamma\in B\) such that

\(\gamma< \alpha\). By the

definition of supremum \(\gamma\) is

not an upper bound. Therefore, there exists \(y \in L\) such that \(\gamma<y\leq \alpha\), so \(y \leq x\) for every \(x \in B\), and hence \(\gamma<x\) for all \(x \in B\). In particular, we obtain \(\gamma<\gamma\) since \(\gamma\in B\), which is

impossible!

Now we show that \(\alpha=\inf B\). We have shown that \(\alpha \in L\), which means that \(\alpha\) is a lower bound of \(B\), since \(\alpha\le x\) for all \(x\in B\). If \(\alpha < \beta\), then \(\beta \not\in L\). If not, we would have \(\alpha < \beta\le \alpha=\sup L\). Since \(\beta\not\in L\) then there exists \(x\in B\) such that \(\beta> x\ge \alpha\). This proves that \(\alpha=\inf B\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Fields

Field 1/2

Field. A field \(\mathbb{F}\) is a set with two binary operations called addition (\(+\)) and multiplication (\((\; \cdot\; )\) or without symbol), which satisfies the following field axioms (A), (M), and (D).

Addition axioms (A).

(A1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\), then \(x+y \in \mathbb{F}\),

(A2) addition is commutative, i.e. \(x+y=y+x\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\),

(A3) addition is associative, i.e. \((x+y)+z=x+(y+z)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{F}\),

(A4) \(\mathbb{F}\) contains the element \(0_{\mathbb{F}}\) such that \(x+0_{\mathbb{F}}=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{F}\),

(A5) to every \(x \in \mathbb{F}\) corresponds an element \((-x) \in \mathbb{F}\) such that \[x+(-x)=0_{\mathbb{F}}.\]

Field 2/2

Multiplication axioms (M).

(M1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\), then their product \(xy \in \mathbb{F}\),

(M2) multiplication is commutative, i.e. \(xy=yx\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\),

(M3) addition is associative, i.e. \((xy)z=x(yz)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{F}\),

(M4) \(\mathbb{F}\) contains the element \(1_{\mathbb{F}}\neq0_{\mathbb{F}}\) such that \(1_{\mathbb{F}}x=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{F}\),

(M5) if \(x \in \mathbb{F}\) and \(x\neq0_{\mathbb{F}}\) then there exists an element \({x}^{-1} =\frac{1}{x}\in \mathbb{F}\) such that \[x \cdot {x}^{-1}=1_{\mathbb{F}}.\]

Distributive law (D).

(D1) \(x(y+z)=xy+xz\) holds for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{F}\).

Field properties - addition

Example 1. \(\mathbb{Q}\) is a field.

Example 2. \(\mathbb{Z}_p\) a set of residue classes of mod \(p\) for any prime number \(p\in\mathbb N\) is a field.

Example 3. \(\mathbb{Z}\) is not a field, because (M5) does not hold, i.e. there is no \(x \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(2x=1\).

Properties of addition. The axioms of addition imply the following:

if \(x+y=x+z\), then \(y=z\),

if \(x=x+y\), then \(y=0_{\mathbb{F}}\),

if \(x+y=0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(y=(-x)\),

\((-(-x))=x\).

Proof of (A). \[\begin{aligned} y&\overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A4)} 0_{\mathbb{F}}+y \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A5)} (-x+x)+y \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A3)} -x+(x+y)\\& \ =-x+(x+z) \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A3)} (-x+x)+z \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A5)} 0_{\mathbb{F}}+z \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A4)} z. \end{aligned}\]

To prove (B), we take \(z=0_{\mathbb{F}}\) in (A).

To prove (C) we take \(z=-x\) in

(A).

Since \(x+(-x)=0_{\mathbb{F}}\), so by (C) with \(-x\) in place of \(x\) we get \[(-(-x))=x.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Field properties - multiplication

Properties of multiplication. The axioms of multiplication imply the following:

if \(x \neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and \(xy=xz\), then \(y=z\),

if \(x \neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and \(x=xy\), then \(y=1_{\mathbb{F}}\),

if \(x \neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and \(xy=1_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(y={x}^{-1}\),

if \(x \neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(\big(x^{-1}\big)^{-1}=x\)

Exercise.

Further field properties

Properties of fields. The field axioms imply the following:

\(x \cdot 0_{\mathbb{F}}=0_{\mathbb{F}}\) for all \(x\in \mathbb{F}\),

if \(x \neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and \(y \neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(xy\neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\),

\((-x)y=-(xy)=x(-y)\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\),

\((-x)(-y)=xy\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\).

For the proof of (A), we use (D1): \[0_{\mathbb{F}}x+0_{\mathbb{F}}x\overbrace{=}^{{\color{brown}(D1)}}(0_{\mathbb{F}}+0_{\mathbb{F}})x=0_{\mathbb{F}}x.\] Thus we must have \(0_{\mathbb{F}}x=0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

To prove (B) assume \(x,y \neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\), but \(xy=0_{\mathbb{F}}\). Then \[1_{\mathbb{F}}={x}^{-1}{y}^{-1}xy={x}^{-1}{y}^{-1}0_{\mathbb{F}}=0_{\mathbb{F}},\] but \(0_{\mathbb{F}} \neq 1_{\mathbb{F}}\).

To prove (C) we write \[(-x)y+xy\overbrace{=}^{{\color{brown}(D1)}}(-x+x)y=0_{\mathbb{F}}y=0_{\mathbb{F}},\] thus \((-x)y=-(xy)\).

To prove \((D)\) we use \((C)\) and we write \[(-x)(-y)=-(x(-y))=-(-(xy))=xy.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Ordered fields

Ordered fields

Definition of an ordered field. An ordered field is a field with is also a totally ordered set such that

if \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{F}\) and \(y<z\), then \(x+y<x+z\),

\(xy>0_{\mathbb{F}}\) if \(x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and \(y>0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

Positive element. The element \(x \in \mathbb{F}\) is called positive if \(x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

Negative element. The element \(x \in \mathbb{F}\) is called negative if \(x<0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

Example. \(\mathbb{Q}\) is an ordered field, but \(\mathbb Z_p\) is not.

Properties of ordered fields

Proposition. The following are true in every ordered field:

if \(x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(-x<0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and vice versa,

if \(x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and \(y<z\), then \(xy<xz\),

if \(x<0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and \(y<z\), then \(xy>xz\),

if \(x \neq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(x \cdot x=x^2>0_{\mathbb{F}}\). In particular, \(1_{\mathbb{F}}>0_{\mathbb{F}}\),

if \(0_{\mathbb{F}}<x<y\), then \(0<{y}^{-1}<{x}^{-1}\).

Proof of (A).

If \(x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(0_{\mathbb{F}}=-x+x>-x+0_{\mathbb{F}}\), thus \(-x<0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

If \(x<0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(0_{\mathbb{F}}=-x+x<-x+0_{\mathbb{F}}\), so that \(-x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

Proof of (B).

Since \(z>y\) we have \(z-y>y-y=0_{\mathbb{F}}\), hence \(x(z-y)>0_{\mathbb{F}}\) if \(x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

Thus \[xz=x(z-y)+xy>0_{\mathbb{F}}+xy=xy.\]

Proof of (C). By (A),(B), and \((-x)y=-(xy)=x(-y)\): \[-(x(z-y))=(-x)(z-y)>0_{\mathbb{F}}\] so

that \(x(z-y)<0_{\mathbb{F}}\) hence

\(xz<xy\).

Proof of (D).

If \(x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\) we get \(x^2>0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

If \(x<0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(-x>0_{\mathbb{F}}\), hence \((-x)^2>0_{\mathbb{F}}\), but \(x^2=(-x)^2\).

We also see \(1_{\mathbb{F}}^2=1_{\mathbb{F}}\), thus \(1_{\mathbb{F}}>0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

Proof of (E).

If \(y>0_{\mathbb{F}}\) and \(v \leq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\), then \(yv \leq 0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

But \({y}^{-1}\cdot y=1_{\mathbb{F}}>0_{\mathbb{F}}\), thus \({y}^{-1}>0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

In similar way \({x}^{-1}>0_{\mathbb{F}}\).

Multiplying the inequality \(x<y\) by \({x}^{-1}{y}^{-1}\) we have \[0_{\mathbb{F}}<{y}^{-1}<{x}^{-1}.\]

$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

A useful lemma

Lemma. Let \((\mathbb F, <)\) be an ordered field. Then, for any \(n \in \mathbb Z \setminus \{0\}\) one has \[n\cdot 1_{\mathbb F}=\underbrace{1_{\mathbb F}+\ldots+1_{\mathbb F}}_{\text{$n$-times}}\neq0_{\mathbb F}.\]

Proof. By the previous proposition \(1\cdot 1_{\mathbb{F}}=1_{\mathbb{F}}>0_{\mathbb{F}}\). Proceeding by induction, suppose we have shown that \(n\cdot 1_{\mathbb F}>0_{\mathbb F}\). Then \[(n+1)\cdot 1_{\mathbb F}=n\cdot 1_{\mathbb F}+1_{\mathbb F}>0_{\mathbb F}+1_{\mathbb F}>0_{\mathbb F}.\] Thus \(n\cdot 1_{\mathbb F}>0_{\mathbb F}\) for every integer \(n>0\). If \(n<0\) we show that \(n\cdot 1_{\mathbb F}<0_{\mathbb F}\) and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The absolute value in ordered fields

Absolute value. Let \(\mathbb F\) be an ordered field an absolute value of \(x\in \mathbb F\) is \[\begin{aligned} |x|=\begin{cases} \hspace{0.295cm} x &\text{ if }x \geq 0, \\ -x &\text{ if }x<0. \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

Properties of \(|x|\). For \(x, y\in \mathbb F\) one has

\(|xy|=|x||y|\),

\(x\le |x|\) and \(x\ge -|x|\),

\(|x+y| \leq |x|+|y|\), (triangle inequality).

\(||x|-|y|| \leq |x-y| \leq |x|+|y|\), (triangle inequality).

If \(x\ge 0\) and \(y\ge 0\) then \(xy\ge0\) and \(|xy|=xy=|x||y|\). If \(x\ge 0\) and \(y< 0\) then \(xy\le 0\) and \(|xy|=-(xy)=x \cdot (-y)=|x||y|\). Two other cases \(x<0\) and \(y\ge0\) or \(x<0\) and \(y<0\) can be covered similarly.

Clearly \(x\le |x|\) for all \(x\in \mathbb R\). Similarly, \(-x\le |x|\) giving \(x\ge-|x|\).

Since \(x\le |x|\) and \(y\le |y|\), then \(x+y\le |x|+|y|\). We also have \(-(|x|+|y|)\le x+y\), since \(-|x|\le x\) and \(-|y|\le y\). Hence \[-( |x|+|y|)\le x+y\le |x|+|y| \qquad \Longleftrightarrow\qquad |x+y| \leq |x|+|y|.\]

Note that \({\color{red}|x|=|y+x-y|\le |y|+|x-y|,}\) and similarly we obtain \({\color{blue}|y|=|x+y-x|\le |x|+|x-y|.}\) Thus \[\begin{aligned} {\color{blue}-|x-y|\le |x|-|y|} \quad \text{ and } \quad {\color{red}|x|-|y|\le |x-y|}, \end{aligned}\] which gives \(||x|-|y|| \leq |x-y|\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Maximum and minimum functions

Let \(\mathbb F\) be an ordered field. Using the absolute value one can define maximum and minimum of two elements from the field.

Maximum and minimum. For any \(x, y\in \mathbb F\) define \[\max\{x, y\}=\frac{x+y+|x-y|}{2},\] and \[\min\{x, y\}=\frac{x+y-|x-y|}{2}.\]

Subfields and field homomorphisms

Definition of a subfield. We say \(\mathbb A\) is a subfield of a field \(\mathbb B\) if \(\mathbb A\) is a field and \(\mathbb A\subseteq \mathbb B\).

Definition of a field homomorphism. Let \((\mathbb A, <_{\mathbb A})\) and \((\mathbb B, <_{\mathbb B})\) be two ordered fields. An ordered field homomorphism \(\varphi: \mathbb A\to \mathbb B\) is a function which preserves the field operations: for all \(x, y\in\mathbb A\) we have \[\begin{gathered} \varphi(x+_{\mathbb A}y)=\varphi(x)+_{\mathbb B}\varphi(y), \qquad \varphi(x\cdot_{\mathbb A} y)=\varphi(x)\cdot_{\mathbb B}\varphi(y)\\ \varphi(0_{\mathbb A})= 0_{\mathbb B}, \qquad \varphi(1_{\mathbb A})= 1_{\mathbb B} \end{gathered}\] and preserves the order relation: for all \(x, y\in\mathbb A\) if \(x<_{\mathbb A}y\) then \[\varphi(x)<_{\mathbb B}\varphi(y).\]

Field embeddings

Injective functions. A function \(f:X\to Y\) is said to be injective if \[f(x_1)=f(x_2) \quad \text{ implies }\quad x_1=x_2.\]

An injective ordered field homomorphism should be thought of as an embedding. We will show that \(\mathbb Q\) can be realized as a subset of any ordered field \(\mathbb F\), in a way that respects all the ordered field structure.

Theorem. Let \((\mathbb F, <)\) be an ordered field. The map \(\varphi:\mathbb Q\to \mathbb F\) given by \[\varphi\bigg(\frac{m}{n}\bigg)=(m\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})\cdot (n\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})^{-1}\] is an injective ordered field homomorphism.

First we must check that \(\varphi\) is well defined: if \(\frac{m_1}{n_1}=\frac{m_2}{n_2}\), then \(m_1n_2=m_2n_1\). By an easy induction it follows that \[(m_1\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})\cdot (n_2\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})=(m_2\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})\cdot (n_2\cdot 1_{\mathbb F}).\] Dividing out on both sides then shows that \(\varphi\) is well-defined, since \[\varphi\bigg(\frac{m_1}{n_1}\bigg)=(m_1\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})\cdot (n_1\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})^{-1}=(m_2\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})\cdot (n_2\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})^{-1}= \varphi\bigg(\frac{m_2}{n_2}\bigg)\]

It is routine to verify that \(\varphi\) is an ordered field homomorphism.

Finally, to show that \(\varphi\) is injective, suppose that \(\varphi(q_1)=\varphi(q_2)\) this means, using the homomorphism property, that \(\varphi(q_1-q_2)=0_{\mathbb F}\). Let \(q_1-q_2=\frac{m}{n}\), then \(0_{\mathbb F}=\varphi(q_1-q_2)=\varphi\big(\frac{m}{n}\big)=(m\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})\cdot (n\cdot 1_{\mathbb F})^{-1}\), which implies that \(m\cdot 1_{\mathbb F}=0_{\mathbb F}\). By the previous lemma this in turn implies that \(m=0\). Thus \(q_1=q_2\) as desired and \(\varphi\) is injective. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$