6. Subsequences and Cauchy Sequences; Monotone Convergence Theorem and Bolzano--Weierstrass Theorem; Cauchy Completeness and; Complex field PDF

Subsequences

Definition. Let \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\), and \(n_1<n_2<\ldots<n_k<\ldots\) be an increasing sequence of positive integers. Then the sequence \[(a_{n_1},a_{n_2},\ldots,a_{n_k},\ldots)\] is called a subsequence of \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and is denoted by \((a_{n_k})_{k \in \mathbb{N}}\).

Example. Let \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}=\left(1,\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{4}\ldots,\right)\), then \(\big(\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{6},\ldots\big) \text{ and }\big(\frac{1}{10},\frac{1}{100},\frac{1}{1000},\ldots\big)\) are subsequences of \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\). The sequences \[\left(\frac{1}{10},\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{100},\ldots\right) \quad \text{ and } \quad (1,1,\ldots)\quad \text{ are {\color{red}NOT!}}.\]

Limit of a subsequence

Theorem. Subsequences of a convergent sequence \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) converge to the same limit as the original sequence.

Proof. Assume \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a\) and let \((a_{n_k})_{k \in \mathbb{N}}\) be a subsequence. Given \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\qquad \text{ implies } \quad |a_n-a|<\varepsilon.\]

Because \(n_k \geq k\) for all \(k \in \mathbb{N}\), the same \(N_{\varepsilon}\) will suffice for the subsequence, that is \[|a_{n_k}-a|<\varepsilon \quad \text{ whenever }\quad k \geq N_{\varepsilon}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cauchy sequences and their properties

Cauchy sequences

Cauchy sequences. A sequence \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) is called Cauchy sequence if for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that whenever \(m,n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) it follows \[|a_n-a_m|<\varepsilon.\]

Convergent sequences. Recall that a sequence \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) converges to \(a \in \mathbb R\) if for any \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(N_{\varepsilon}\in \mathbb{N}\) such that whenever \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) if follows \[|a_n-a|<\varepsilon.\]

Convergent sequences are Cauchy

Theorem. Every convergent sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) is a Cauchy sequence.

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. If \[\lim_{n \to \infty}x_n=x,\]

then there is \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) implies \[|x_n-x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\]

Thus for \(n,m \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) we obtain \[\begin{aligned} |x_m-x_n| \leq |x_n-x|+|x_m-x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon. \end{aligned}\] The proof is completed. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cauchy sequences are bounded

Lemma. Cauchy sequences \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) are bounded.

Proof. Let \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) be Cauchy. Given \(\varepsilon=1\) there is \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) so that if \(n,m \geq N\) then \(|x_n-x_m|<1\). Thus

\[|x_n| \leq |x_N|+1.\]

Taking \[M=\max\{|x_1|,|x_2|,\ldots,|x_N|,|x_N|+1 \}\]

we conclude \(|x_n| \leq M\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cauchy sequences and converging subsequences

Theorem. Let \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) be a Cauchy sequence. Suppose that there is \((n_k)_{k \in \mathbb{N}}\) so that \(\lim_{k \to \infty}x_{n_k}=x\). Then \(\lim_{n \to \infty}x_{n}=x\).

Proof. Assume that \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) is Cauchy and there is \((n_k)_{k \in \mathbb{N}}\) so that \[\lim_{k \to \infty}x_{n_k}=x \in \mathbb{F} \qquad {\color{red}(*)}.\] Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Then there is \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \(n,m \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) implies \(|x_n-x_m|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\). By (*) we can choose \(n_k \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \(n_k \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) and \[|x_{n_k}-x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\] Then for \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) and the triangle inequality \[|x_n-x| \leq |x_{n}-x_{n_k}|+|x_{n_k}-x| <\frac{\varepsilon}{2}+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon. \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Increasing and decreasing sequences

Increasing and decreasing sequences. Let \(\mathbb R\) be an ordered field. A sequence of real numbers \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) is

increasing if \(a_n \leq a_{n+1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\);

decreasing if \(a_n \geq a_{n+1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Monotone sequence. A sequence is monotone if it is either increasing or decreasing.

Example.

\(\left(3+\frac{1}{n}\right)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is decreasing, so it is monotone.

\(\left(n^{3}\right)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is increasing, so it is monotone.

\(\left((-1)^n\right)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is neither increasing nor decreasing, so it is not monotone.

Consequences of the (AoC) and nested intervals property

Monotone convergence theorem

Monotone convergence theorem (MCT). If a sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq\mathbb R\) is monotone and bounded then it converges.

Proof. Assume that \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is increasing and bounded. Consider the set \[E=\{x_n\colon n \in \mathbb{N}\} \subseteq \mathbb{R},\] which is nonempty and bounded. Let \({\color{blue}x=\sup E \in \mathbb{R}}\), which exists by the axiom of completeness (AoC). We will show that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}x_n={\color{blue}x}.\)

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) and note that there exists \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[x-\varepsilon<x_{N_{\varepsilon}} \leq x.\]

But \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is increasing thus for any \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) one has \[x-\varepsilon<x_{N_{\varepsilon}} \leq x_{n} \leq x<x+\varepsilon.\]

Hence \(|x_n-x|<\varepsilon\) for all \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\), which shows that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}x_n=x\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem

Every bounded sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq\mathbb R\) contains a convergent subsequence.

Proof. Let \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq \mathbb R\) be bounded. Then there is \(M>0\) such that \[|a_n| \leq M\quad \text{ for all } \quad n \in \mathbb{N}.\]

Thus \(a_n \in [-M,M]\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

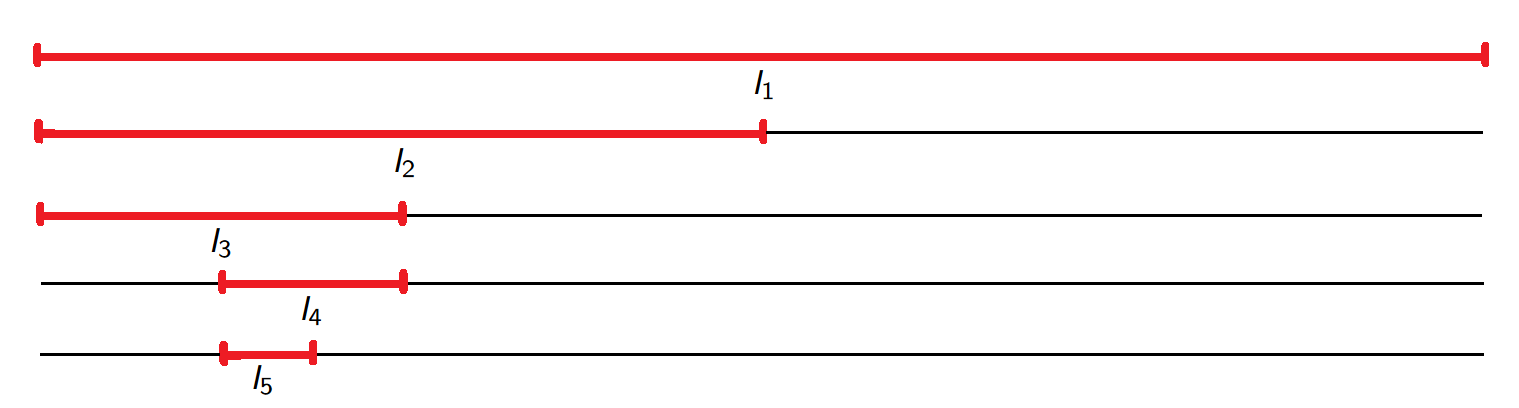

Step 1. Divide \([-M,M]\) into two closed intervals \([-M,0]\), \([0,M]\). We can assume (wlog) that \(I_1=[0,M]\) contains infinitely many elements of \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\). Moreover, the length of \(I_1\) is \(M\).

Step 2. Divide \(I_1\) into two closed intervals of the same length and select the one which contains infinitely many elements of \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\). Call it \(I_2 \subset I_1\) and note that has length \(\frac{M}{2}\).

Step 3. Proceeding inductively as above we obtain a sequence of decreasing closed intervals \[I_1 \supset I_2 \supset I_3 \supset I_4 \supset \ldots\] where each \(I_k\) contains infinitely many elements of \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and has length \(\frac{M}{2^{k-1}}\).

Step 4. By the nested intervals property \(\bigcap_{k=1}^{\infty}I_k \neq \varnothing\). In fact, \[\bigcap_{k=1}^{\infty}I_k =\{x\} \quad \text{ for some }\quad x \in \mathbb R \quad \text{\color{red} why?}.\] Now for each \(k \in \mathbb{N}\) select an element \(a_{n_k} \in I_{k}\) so that \[n_1<n_2<\ldots< n_k<\ldots\] where \(a_{n_1}\) is any element of \(I_1\).

Step 5. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) and choose \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[\frac{M}{2^{k-1}}\le \frac{2M}{k}<\varepsilon \quad \text{ for }\quad k \geq N_{\varepsilon}.\] Then for every \(k \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) we have \[|a_{n_k}-x|\leq \frac{M}{2^{k-1}}<\varepsilon,\] thus \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_{n_k}=x\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem implies Cauchy completeness

Example. Let us consider a sequence \(a_n=(-1)^n.\) It in NOT convergent, but the subsequence \((-1)^{2n}=1\) converges to \(1\).

A sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges iff it is a Cauchy sequence.

Proof: The implication \((\Longrightarrow)\) has already been proved. For the reverse implication \((\Longleftarrow)\) assume that \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is Cauchy, thus it is bounded. By the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem there is \((n_k)_{k \in \mathbb{N}}\) so that \[\lim_{k \to \infty}x_{n_k}=x \quad \text{ for some }\quad x\in \mathbb R.\] But Cauchy sequences with converging subsequences converge, i.e. \[\lim_{n \to \infty}x_{n}=x.\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The complex field

Complex numbers

A complex number is an ordered pair \((a, b)\in\mathbb R\times \mathbb R\).

For two complex numbers \(x=(a, b), y=(c, d)\in\mathbb R\times \mathbb R\) we define

addition \({\color{blue}+}\) by setting \[x+y=(a+c, b+d),\]

multiplication \({\color{blue}\cdot}\) by setting \[x\cdot y=(ac-bd, ad+bc).\]

Complex field

These operations addition \({\color{blue}+}\) and multilpication \({\color{blue}\cdot}\) turn the set of all complex numbers into a field with \((0,0)\) and \((1, 0)\) playing, respectively, the role of \(0\) and \(1\). This field will be denoted by \(\mathbb C\).

Proof.

We have to verify the field axioms.

Addition axioms (A).

(A1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{C}\), then \(x+y \in \mathbb{C}\),

(A2) \(x+y=y+x\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{C}\),

(A3) \((x+y)+z=x+(y+z)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{C}\),

(A4) \(\mathbb{C}\) contains the element \(0\) such that \(x+0=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{C}\),

(A5) to every \(x \in \mathbb{C}\) corresponds an element \((-x) \in \mathbb{C}\) such that \[x+(-x)=0.\]

Multiplication axioms (M).

(M1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{C}\), then their product \(xy \in \mathbb{C}\),

(M2) \(xy=yx\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{C}\),

(M3) \((xy)z=x(yz)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{C}\),

(M4) \(\mathbb{C}\) contains the element \(1\neq0\) such that \(1\cdot x=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{C}\),

(M5) if \(0\neq x \in \mathbb{C}\) then there is an element \({x}^{-1} =\frac{1}{x}\in \mathbb{C}\) such that \[x \cdot {x}^{-1}=1.\]

Distributive law (D).

(D1) \(x(y+z)=xy+xz\) holds for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{C}\).

Let \(x=(a, b), y=(c,d), z=(e,f)\). We will use the field structure of \(\mathbb R\).

Proof of (A1). By the definition of addition \[x+y=(a, b)+(c, d)=(a+c, b+d)\in\mathbb C.\]

Proof of (A2). \[x+y=(a+c, b+d)=(c+a)+(d+b)=y+x.\]

Proof of (A3). \[\begin{aligned} (x+y)+z&=(a+c, b+d)+(e, f)\\ &=(a+c+e, b+d+f)\\ &=(a, b)+(c+e, d+f)=x+(y+z). \end{aligned}\]

Proof of (A4). \[x+0=(a, b)+(0,0)=(a, b)=x.\]

Proof of (A5). Set \(-x=(-a, -b)\) and note that \[x+(-x)=(a-a, b-b)=(0,0)=0.\]

Proof of (M1). By the definition of multiplication \[x\cdot y=(a, b)\cdot(c, d)=(ac-bd, ad+bc)\in\mathbb C.\]

Proof of (M2). \[x\cdot y=(ac-bd, ad+bc)=(ca-db, da+cb)=y\cdot x.\]

Proof of (M3). \[\begin{aligned} (x\cdot y)\cdot z&=(ac-bd, ad+bc)\cdot(e, f)\\ &=(ace-bde-adf-bcf, acf-bdf+ade+bce)\\ &=(a, b)\cdot(ce-df, cf+de)=x\cdot (y\cdot z). \end{aligned}\]

Proof of (M4). \[1\cdot x=(1, 0)\cdot (a, b)=(a, b)=x.\]

Proof of (M5). If \(x\neq0\) then \((a, b)\neq(0, 0)\), which means that at least one of the real numbers \(a, b\) is different from \(0\). Hence \(a^2+b^2>0\) and we define \[\frac{1}{x}=\bigg(\frac{a}{a^2+b^2}, \frac{-b}{a^2+b^2}\bigg).\] Then \[x\cdot \frac{1}{x}=(a, b)\cdot\bigg(\frac{a}{a^2+b^2}, \frac{-b}{a^2+b^2}\bigg)=(1, 0).\]

Proof of (D1). \[\begin{aligned} x\cdot(y+z)&=(a, b)\cdot(c+e, d+f)\\ &=(ac+ae-bd-bf, ad+af+bc+be)\\ &=(ac-bd, ad+bc)+(ae-bf, af+be)\\ &=x\cdot y+x\cdot z. \end{aligned}\] This completes the proof that \(\mathbb C\) is a field.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Imaginary number \(i\)

Remark. For any \(a, b\in \mathbb R\) we have \[ (a, 0)+(b, 0)=(a+b, 0) \quad \text{ and } \quad (a, 0)\cdot (b, 0)=(ab, 0).\]

The complex numbers from the set \(\{(a, 0): a\in\mathbb R\}\) have the same arithmetic properties as the corresponding real numbers \(\mathbb R\).

We can therefore identify \((a, 0)\) with \(a\). This identification gives us the real field \(\mathbb R\) as a subfield of the complex field \(\mathbb C\).

We have defined the complex numbers \(\mathbb C\) without any reference to the mysterious square root of \(-1\). We now show that the notation \((a, b)\) is equivalent to the more customary \(a + bi\).

We define the imaginary number by setting \(i=(0, 1)\).

Equivalent definition of \(\mathbb C\)

One has that \(i^2=-1\).

Proof. Note that \(i^2=(0, 1)\cdot(0, 1)=(-1, 0).\)$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

We also have \[\mathbb C=\{a+ib: a, b\in\mathbb R\}.\]

Proof. It suffices to note that \[\begin{aligned} a+ib&=(a, 0)+(0,1)\cdot(b, 0)\\ &=(a, 0)+(0, b)=(a, b). \end{aligned}\]$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Conjugate, real and imaginary parts

If \(z\in\mathbb C\) and \(z=a+ib\) for some \(a,b \in\mathbb R\) then the complex number \[\overline{z}=a-ib\] is called the conjugate of \(z\). The numbers \(a\) and \(b\) are the real part and imaginary part of \(z\) respectively. We shall write \[a=\Re(z)={\rm Re}(z) \quad\text{ and } \quad b=\Im(z)={\rm Im}(z).\]

If \(z, w\in\mathbb C\) then

\(\overline{z+w}=\overline{z}+\overline{w}.\)

\(\overline{zw}=\overline{z} \cdot \overline{w}.\)

\(z+\overline{z}=2{\rm Re}(z)\) and \(z-\overline{z}=2i{\rm Im}(z)\).

\(z\overline{z}\) is a positive real number except when \(z=0\).

Proof.

Let \(z=a+ib\) and \(w=c+id\).

Proof of (i). Note that \[\overline{z+w}=\overline{(a+c)+i(b+d)}=(a+c)-i(b+d)=\overline{z}+\overline{w}.\]

Proof of (ii). Note that \[\begin{aligned} \overline{z\cdot w}&=(ac-bd)-i (ad+bc) \quad \text{ and }\\ \overline{z} \cdot \overline{w}&=(a-ib)(c-id)=(ac-bd)-i (ad+bc). \end{aligned}\]

Proof of (iii). We have \[\begin{aligned} z+\overline{z}&=(a+ib)+(a-ib)=2a=2{\rm Re}(z),\\ z-\overline{z}&=(a+ib)-(a-ib)=2ib=2i{\rm Im}(z). \end{aligned}\]

Proof of (iv). We have \(z\cdot\overline{z}= (a+ib)(a-ib)=a^2+b^2>0\) if and only if \(z\neq0\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Absolute value on \(\mathbb C\)

If \(z\in\mathbb C\) its absolute value \(|z|\) is defined by setting \[|z|=\sqrt{z\cdot\overline{z}}.\]

Remark. This absolute value exists and is unique. Moreover, it coincides with the absolute value from \(\mathbb R\). If \(x\in \mathbb R\) then \(\overline{x}=x\) hence \(|x|=\sqrt{x\cdot \overline{x}}=\sqrt {x^2}\). Thus \[|x|= \begin{cases} x & \text{ if } x\le 0,\\ -x& \text{ if } x< 0. \end{cases}\]

Properties of the absolute value on \(\mathbb C\)

If \(z, w \in\mathbb C\) then

\(|z|>0\) if and only if \(z\neq 0\), and \(|0|=0\).

\(|\overline{z}|=|z|\).

\(|zw|=|z||w|\).

\(|{\rm Re}(z)|\le |z|\) and \(|{\rm Im}(z)|\le|z|\)

\(|z+w|\le |z|+|w|\).

Proof.

Let \(z=a+ib\) and \(w=c+id\).

Proof of (i). From the previous theorem we have \[|z|^2=z\cdot\overline{z}= (a+ib)(a-ib)=a^2+b^2>0,\] which gives the desired claim.

Proof of (ii). Note that \(|z|^2=a^2+b^2=|\overline{z}|^2\).

Proof of (iii). Note that \[\begin{aligned} |z\cdot w|=(ac-bd)^2+ (ad+bc)^2 =(a^2+b^2)(c^2+d^2)=|z|^2|w|^2. \end{aligned}\]

Proof of (iv). We have \[\begin{aligned} |{\rm Re}(z)|=|a|\le \sqrt{a^2+b^2}=|z|, \ \text{ and } \ |{\rm Im}(z)|=|b|\le \sqrt{a^2+b^2}=|z|. \end{aligned}\]

Proof of (v). Note that \(\overline{z}w\) is the conjugate of \(z\overline{w}\) so that \(z\overline{w}+\overline{z}w=2{\rm Re}(z\overline{w})\). Hence \[\begin{aligned} |z+w|^2&=(z+w)(\overline{z}+\overline{w})=z\overline{z}+z\overline{w}+\overline{z}w+ w\overline{w}\\ &=|z|^2+2{\rm Re}(z\overline{w})+|w|^2\\ &\le |z|^2+2|{\rm Re}(z\overline{w})|+|w|^2\\ &=|z|^2+2|z||w|+|w|^2=(|z|+|w|)^2. \end{aligned}\]

The proof of the theorem is completed. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Convergence in \(\mathbb C\)

We say that a sequence of complex numbers \((z_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\subseteq \mathbb C\) converges to \(z\in \mathbb C\) if and only if \[\lim_{n\to \infty}|z_n-z|=0.\] We write \[\lim_{n\to \infty}z_n=z \quad \text{ if and only if }\quad \lim_{n\to \infty}|z_n-z|=0.\] This is also equivalent to say that for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there exists an integer \(N_{\varepsilon}\in\mathbb N\) such that if \(n\ge N_{\varepsilon}\) then \[|z_n-z|<\varepsilon.\]