16. Metric spaces basic properties PDF

Metric spaces

Metric spaces

Metric. A metric on a set \(X\) is a function \(\rho:X \times X \to [0,\infty)\) such that

\(\rho(x,y)=0\) iff \(x=y\),

\(\rho(x,y)=\rho(y,x)\) for all \(x,y, \in X\),

\(\rho(x,y) \leq \rho(x,z)+\rho(z,y)\) for all \(x,y,z \in X\).

The function \(\rho(x,y)\) can be identified as the distance from \(x\) to \(y\).

Metric space. A set \(X\) equipped with a metric \(\rho\) is called a metric space and denoted by \((X,\rho)\).

Metric spaces - examples

Example 1. The set \(\mathbb{R}\) with \(\rho(x,y)=|x-y|\) is a metric space. Clearly t \(\rho\) is a metric:

\(\rho(x,y)=|x-y|=0 \iff x-y=0 \iff x=y\).

\(\rho(x,y)=|x-y|=|y-x|=\rho(y,x)\),

\(\rho(x,y)=|x-y| \leq |x-z|+|z-y|=\rho(x,z)+\rho(z,y)\).

Example 2. If \(X\) is any set, then \[\rho(x,y)=\begin{cases} 0 \text{ if }x \neq y, \\ 1 \text{ if }x=y \end{cases}\] is discrete metric and \((X,\rho)\) is a discrete space.

Example 3. Consider \(d\)-dimensional vector space \(\mathbb{R}^d=\overbrace{\mathbb{R} \times \ldots \times \mathbb{R}}^{d \text{ times}}\) and for vectors \(x=(x_1,\ldots,x_d) \in \mathbb{R}^d\), \(y=(y_1,\ldots,y_d) \in \mathbb{R}^d\) define \[\begin{aligned} \rho_2(x,y)&=\left(\sum_{j=1}^d|x_j-y_j|^2\right)^{1 / 2}\\ \rho_1(x,y)&=\sum_{j=1}^d|x_j-y_j|,\\ \rho_{\infty}(x,y)&=\max_{1 \leq j \leq d}|x_j-y_j|. \end{aligned}\]

It is not difficult to see that \(\rho_2\), \(\rho_1\), \(\rho_\infty\) are metrics on \(\mathbb{R}^d\).

Example 4. Consider infinite dimensional vector space \(\mathbb{R}^{\mathbb{N}}\), and for vectors \(x=(x_1,x_2,\ldots)\in \mathbb{R}^{\mathbb{N}}\), \(y=(y_1,y_2,\ldots)\in \mathbb{R}^{\mathbb{N}}\), define \[\rho(x,y)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{2^n}\min(1,|x_n-y_n|),\] which is a metric on \(\mathbb{R}^{\mathbb{N}}\).

Example 5. If \(\rho\) is a metric on \(X\) and \(A \subseteq X\) then \(\rho|_{A \times A}\) is a metric on \(A\).

Example 6. Let \((X_1,\rho_1),\ldots,(x_d,\rho_d)\) be metric spaces, and consider their product \(X=X_1 \times \ldots \times X_d\). For \(x=(x_1,\ldots,x_d) \in X\), \(y=(y_1,\ldots,y_d) \in X\), define functions \[\begin{aligned} d_1(x,y)&=\sum_{j=1}^d \rho_j(x_j,y_j),\\ d_2(x,y)&=\left(\sum_{j=1}^d \rho_j(x_j,y_j)^2\right)^{1 / 2},\\ d_{\infty}(x,y)&=\max_{1 \leq j \leq d}\rho_j(x_j,y_j), \end{aligned}\] which are metrics on \(X\).

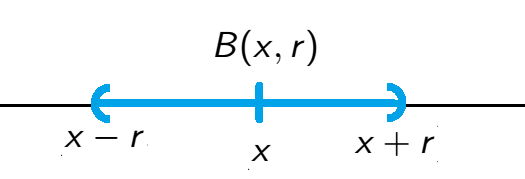

Balls

Ball. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space. If \(x \in X\) and \(r>0\), the open ball of radius \(r\) and center \(x\) is \[B(x,r)=\{y \in X\;:\;\rho(x,y)<r\}.\]

Example 1. For \(\mathbb{R}\) with \(\rho(x,y)=|x-y|\), the ball \(B(x,r)=(x-r,x+r)\) is an interval of length \(2r\) centered at \(x\):

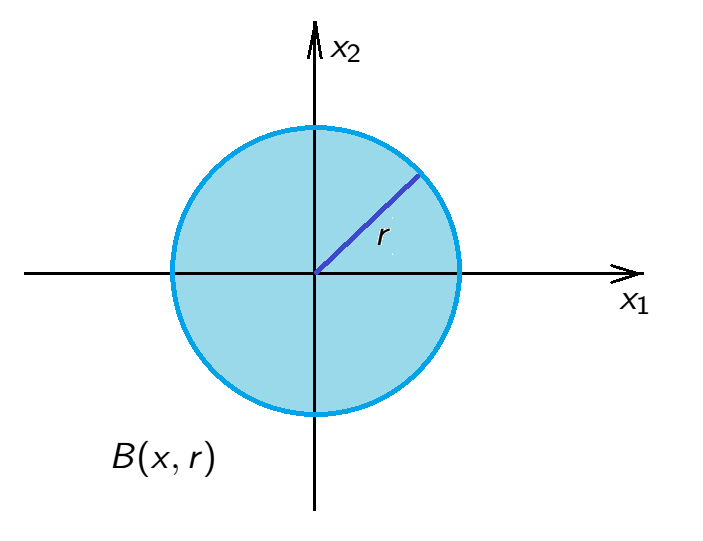

Example 2

\(\mathbb{R}^2\) with \(\rho_2(x,y)=\sqrt{|x_1-y_1|^2+|x_2-y_2|^2}\), \(x=(x_1,x_2)\), \(y=(y_1,y_2)\). \[\begin{aligned} B(x,r)&=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;\rho_2(x,y)<r\}\\ &=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\; (y_1-x_1)^2+(y_2-x_2)^2 <r^2\} \end{aligned}\]

\[{\color{blue}B(0,r)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;y_1^2+y_2^2<r^2\}}\]

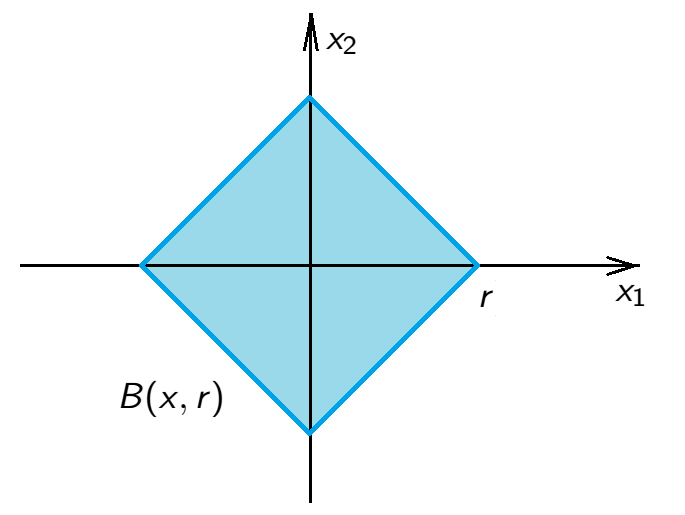

Example 3

\(\mathbb{R}^2\) with \(\rho_1(x,y)=|x_1-y_1|+|x_2-y_2|\), \(x=(x_1,x_2)\), \(y=(y_1,y_2)\). \[B(x,r)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;\rho_1(x,y)<r\}\]

\[{\color{blue}B(0,r)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;\rho_1(0,y)<r\}}\]

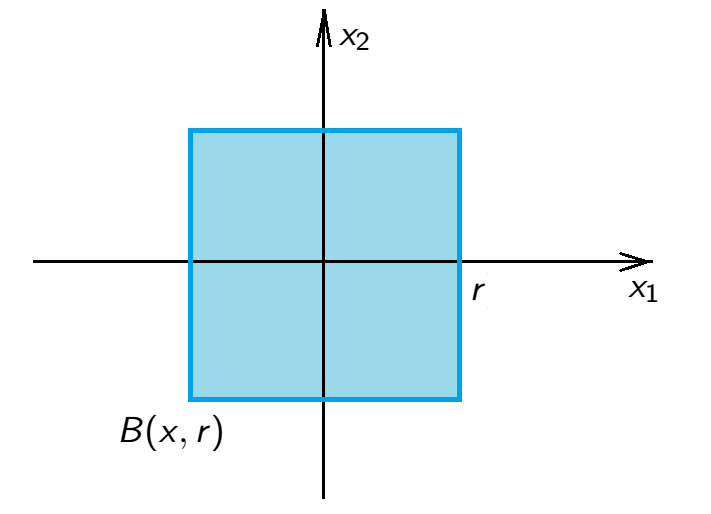

Example 4

\(\mathbb{R}^2\) with \(\rho_\infty(x,y)=\max(|x_1-y_1|,|x_2-y_2|)\), \(x=(x_1,x_2)\), \(y=(y_1,y_2)\). \[B(x,r)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;\rho_\infty(x,y)<r\}\]

\[{\color{blue}B(0,r)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;\rho_\infty(0,y)<r\}}\]

Open and closed sets

Open set. A set \(E \subseteq X\) is open if for every \(x \in E\) there exists \(r>0\) such that \(B(x,r) \subseteq E\).

Closed set. A set \(E \subseteq X\) is closed if its complement \(X \setminus E\) is open.

Open sets - examples

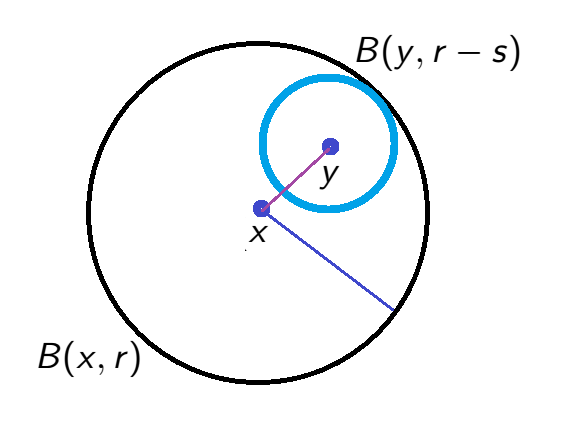

Example 1. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space. Every ball \(B(x,r)\) is open, if \(y \in B(x,r)\) and \(\rho(x,y)=s\), then \[B(y,r-s) \subseteq B(x,r).\]

Indeed, \(z \in B(y,r-s) \iff \rho(y, z)<r-s\), then \[\rho(x,z) \leq \rho(x,y)+\rho(y,z)<s+r-s=r \iff z \in B(x,r).\]

Example 2. \(X\) and \(\varnothing\) are both open and closed.

Example 3. The union of any family of open sets is open. In other words, if \((U_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a family of subsets of \(X\) such that each \(U_{\alpha} \subseteq X\) is open, then \[\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}U_{\alpha} \text{ is also open.}\]

Example 4. The intersection of any finite family of open sets is open.

Indeed, if \(U_1,\ldots,U_n\) are open and \(x \in \bigcap_{j=1}^n U_j\), then for each \(1 \leq j \leq n\) there exists \(r_j>0\) such that \[B(x,r_j) \subseteq U_j\] and then \[\begin{aligned} B(x,r) \subseteq \bigcap_{j=1}^n U_j \quad \text{ if } \quad r=\min\{r_1,\ldots,r_n\}, \end{aligned}\] so \(\bigcap_{j=1}^n U_j\) is open.

Remark

By passing to the complements

The intersection of any family of closed sets is closed.

The union of any finite family of closed sets is closed.

Example 1. If \(x_1,x_2 \in X\), then \[X \setminus B(x_1,r) \cup X \setminus B(x_2,r)\] is closed for any \(r>0\).

Interior and closure

Let \(X\) be a metric space and let \(E \subseteq X\).

Interior of \(E\). The union of all open sets \(U \subseteq E\) is the largest open set contained in \(E\) and it is called the interior of \(E\) and it is denoted by \[{\rm int\;}E.\]

Closure of \(E\). The intersecion of all closed sets \(F \supseteq E\) is the smallest closed set containing \(E\) and it is called the closure of \(E\) and it is denoted by \[{\rm cl\;}(E)\quad or\quad \overline{E}.\]

Observations

Let \(X\) be a metric space and let \(A \subseteq X\). We have the following facts.

\(({\rm int\;}A)^c={\rm cl\;}(A^c)\),

\(({\rm cl\;}A)^c={\rm int\;}(A^c)\).

Proof of (i). Observe that \({\rm int\;}A \subseteq A\) iff \(A^c \subseteq ({\rm int\;}A)^c\). Then \({\rm cl\;}(A^c)\) as a closed set satisfies \[{\rm cl\;}(A^c) \subseteq ({\rm int\;}A)^c.\]

Next we show that \[{\rm cl\;}(A^c) \supseteq ({\rm int\;}A)^c.\] Indeed, \(({\rm cl\;}(A^c))^c \subseteq A\) and \(({\rm cl\;}(A^c))^c\) is open, so \(A^c \subseteq {\rm cl\;}(A^c)\), thus \(\left({\rm cl\;}(A^c)\right)^c \subseteq {\rm int\;}(A)\), so \[({\rm int\;}A)^c \subseteq {\rm cl\;}(A^c).\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Examples of open and closed sets on \(\mathbb{R}\)

Let \(-\infty \leq a <b \leq +\infty\).

Example 1. \((a,b)\) is open in \(\mathbb{R}\) (it is a ball).

Example 2. \(\mathbb{Z}\) is closed in \(\mathbb{R}\) since \[\mathbb{Z}^c=\bigcup_{n \in \mathbb{Z}}(n,n+1)\] is open.

Example 3. \([a,b]\) is closed in \(\mathbb{R}\) since \[[a,b]^c=(-\infty,a) \cup (b,+\infty)\quad \text{ is open.}\]

Proposition

Proposition. Every open set in \(\mathbb{R}\) is a countable disjoint union of open intervals.

Proof. If \(U\) is open, for each \(x \in U\) consider the collection \(\mathcal{F}_x\) of all open intervals \(I\) such that \(x \in I \subseteq U\).

It is easy to see that the union of any family of open intervals containing a point in common is again an open interval and hence \[J_x=\bigcup_{I \in \mathcal{F}_x}I\] is an open interval.

Moreover, it is the largest element of \(\mathcal{F}_x\). If \(x,y \in U\) then either \[J_x=J_y \quad \text{ or } \quad J_x \cap J_y = \varnothing.\] For otherwise \(J_x \cup J_y\) would be a larger open interval than \(J_x\) in \(\mathcal{F}_x\).

Thus if \[\mathcal{F}=\{\mathcal{F}_x\;:\;x \in U\}\] then the distinct members of \(\mathcal{F}\) are disjoint and \[U=\bigcup_{J \in \mathcal{F}}J.\]

For each \(J \in \mathcal{F}\) pick a rational number \(f(J) \in J\). The map \(f:\mathcal{F} \to \mathbb{Q}\) is injective, for \(J \neq J'\) then \[J \cap J' = \varnothing \quad \text{ and }\quad f(J) \neq f(J').\]

Hence \({\rm card\;}(\mathcal{F}) \leq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{Q})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\), so \(\mathcal{F}\) is countable. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Dense sets

Dense set. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space, \(E \subseteq X\) is said to be dense in \(X\) if \[E \cap U \neq \varnothing\] for every open set \(U\) in \(X\).

Equivalently, \(E \subseteq X\) is said to be dense if \(E \cap B(x,r) \neq \varnothing\) for every \(x \in X\) and \(r>0\).

Examples.

\(\mathbb{Q}\) is dense in \(\mathbb{R}\),

\(\mathbb{Q}^d\) is dense in \(\mathbb{R}^d\),

\(\Delta=\{k2^{-n}\;:\;0 \leq k \leq 2^n\}\) is dense in \([0,1]\),

if \(\alpha \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \mathbb{Q}\), then \(\{n \alpha-\lfloor n\alpha\rfloor\;:\;n \in \mathbb{Z}\}\) is dense in \([0,1]\).

Nowhere dense set

Nowhere dense set. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space, \(E \subseteq X\) is said to be nowhere dense if \(E\) has empty interior, i.e. \[{\rm int\;}({\rm cl\;}E) = \varnothing.\]

Examples.

\(X=\mathbb{R}\), then \(\{x\}\) for every \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) is nowhere dense in \(\mathbb{R}\).

\(X=\mathbb{R}\), then \(\mathbb{Z}\) is nowhere dense in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Separable space

Separable space. A metric space \((X,\rho)\) is called separable if it has a countable dense subset.

Examples.

\(\mathbb{R}\) is separable since \(\mathbb{Q}\) is dense and countable.

\(\mathbb{R}^d\) is separable since \(\mathbb{Q}^d\) is dense and countable.

Convergence in metric spaces

Convergence in metric spaces. A sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) in a metric space \((X,\rho)\) is said to converge if there is a point \(x \in X\) with the following property: For every \(\varepsilon>0\) there is an integer \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon} \quad \text{implies} \quad \rho(x_n,x)<\varepsilon.\]

In this case we also say that \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges to \(x\) or that \(x\) is the limit of \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and we write \[x_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ x\quad \text{ or }\quad \lim_{n \to \infty}x_n=x \quad \text{ or } \quad \lim_{n \to \infty}\rho(x_n,x)=0.\]

Divergence. If \((x_n)_{n=1}^{\infty}\) does not converge it is said to diverge.

Diameter of a set and bounded sets

Diameter of a set. In a metric space \((X,\rho)\) we define the diameter of \(E \subseteq X\) to be \[{\rm diam\;}(E)=\sup\{\rho(x,y)\;:\;x,y \in E\}.\]

Bounded set. \(E\) is called bounded if \({\rm diam\;}(E)<\infty\).

Examples.

\(\{x\}\) is bounded, \({\rm diam\;}(\{x\})=0\),

\(B(x,r)=\{y \in X\;:\;\rho(x,y)<r\}\) is bounded, since if \(x_1,x_2 \in B(x,r)\), then \(\rho(x_1,x_2) \leq \rho(x_1,x)+\rho(x,x_2)<2r.\) Thus \({\rm diam\;}(B(x,r)) \leq 2r\).

\((a,b) \subseteq \mathbb{R}\), \(-\infty<a<b<\infty\), then \({\rm diam\;}((a,b))=b-a\).

Bounded sequences

Bounded sequences. The sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) in \((X,\rho)\) is said to be bounded if its range is bounded, i.e. \[{\rm diam\;}(\{x_n \in X\;:\;n \in \mathbb{N}\})<\infty.\]

Theorem. Let \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) be a sequence in a metric space \((X,\rho)\).

\((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges to \(x \in X\) iff every open set containing \(x\) contains \(x_n\) for all but finitely many \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

If \(x,x' \in X\) and if \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges to \(x\) and \(x'\), then \(x=x'\).

If \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges then \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is bounded.

Proof of (i) (\(\Longrightarrow\)). \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\rho(x_n,x)=0\) means that for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that

(*). \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon} \quad \text{implies} \quad \rho(x_n,x)<\varepsilon.\]

Take an open set \(V\) so that \(x \in V\). Sicne \(V\) is open then there is \(r>0\) such that \(B(x,r) \subseteq V\). It suffices to take \(\varepsilon<r\) in (*) to see that \(x_n \in B(x,r)\) for all \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) since \(\rho(x_n,x)<\varepsilon\) by (*). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof of (i) (\(\Longleftarrow\)). Conversely suppose that every open set \(V\) containing \(x\) contains all but finitely many of \(x_n\)’s. Take \(\varepsilon>0\) and consider \(V=B(x,\varepsilon)\), this set is open and \(x \in V\). By assumption there exists \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) (depending on \(V\)) such that \(x_n \in B(x,\varepsilon)\) for all \(n \geq N\). Thus \(\rho(x_n,x)<\varepsilon\) if \(n \geq N\). Hence \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\rho(x_n,x)=0\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof of (ii). Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. There are \(N_{\varepsilon},N'_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that

\[n \geq N_{\varepsilon} \quad \text{ implies }\quad \rho(x_n,x)<\frac{\varepsilon}{2},\]

\[n \geq N'_{\varepsilon} \quad \text{ implies }\quad \rho(x_n,x')<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\]

Hence if \(n \geq \max(N_{\varepsilon},N'_{\varepsilon})\), then by triangle inequality, we have \[\rho(x,x') \leq \rho(x,x_n)+\rho(x',x_n)<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon.\]

Since \(\varepsilon>0\) was arbitrary, \(\rho(x,x')=0\) and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof of (iii). Suppose that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\rho(x_n,x)=0\). Then there is \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N \quad \text{ implies }\quad \rho(x_n,x)<1.\]

Let \({\color{blue}r=\max\{1,\rho(x_1,x),\ldots,\rho(x_N,x)\}}\). Then we see that \[\rho(x_n,x) \le r\quad \text{ for all }\quad n \in \mathbb{N}.\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proposition

Proposition. If \((X,\rho)\) is a metric space, \(E \subseteq X\) and \(x \in X\), the following are equivalent.

\(x \in {\rm cl\;}(E)\),

\(B(x,r) \cap E \neq \varnothing\) for all \(r>0\),

There is a sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) in E that converges to \(x\).

Proof \((a) \implies (b)\). If \(B(x,r) \cap E =\varnothing\), then \(B(x,r)^c\) is a closed set containing \(E\) but not \(x\), so \[E \subseteq {\rm cl\;}(E) \subseteq B(x,r)^c\] and consequently \(x \not\in {\rm cl\;}(E)\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof \((b) \implies (a)\). If \(x \not\in {\rm cl\;}(E)\), since \({\rm cl\;}(E)^c\) is open there is \(r>0\) so that \(B(x,r) \subseteq ({\rm cl\;}(E))^c \subseteq E^c\), so \(B(x,r) \cap E=\varnothing\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof \((b) \implies (c)\). For each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) there exists \(x_n \in B(x,1 / n) \cap E\) hence \[\rho(x_n,x)<\frac{1}{n}\] and consequently \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\rho(x_n,x)=0\] as desired.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof \((c) \implies (b)\). If \(B(x,r) \cap E =\varnothing\), then

\[\rho(y,x)\geq r\] for all \(y \in E\), so no sequence of \(E\) can converge to \(x\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Accumulation and isolated points

Accumulation point. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space, \(x \in X\) is called an accumulation point of \(E \subseteq X\) if for every open set \(U \ni x\) we have \[(E \setminus \{x\}) \cap U \neq \varnothing.\]

An accumulation point \(x\) of \(E \subseteq X\) is sometimes also called a limit point of \(E\) or a cluster point of \(E\).

Isolated point. A point \(x \in E\) is called an isolated point of \(E\) if it is not an accumulation point of \(E\).

Examples

Example 1. \(X=\mathbb{R}\), \(E=[a,b]\), \(-\infty<a<b<\infty\), each \(x \in E\) is an accumulation point of \(E\).

Example 2. \(X=\mathbb{R}\), \(E=(a,b)\), \(-\infty<a<b<\infty\), each point of \(x \in [a,b]\) is an accumulation point of \(E\).

Example 3. \(X=\mathbb{R}\), \(E=\mathbb{Z}\), each point of \(\mathbb{Z}\) is an isolated point.

Remark. If \(x \in X\) is a limit point of \(E \subseteq X\) it does not need to be an element of \(E\).

Perfect space

Perfect space. A set \(E \subseteq X\) of a metric space is called perfect if \(E={\rm acc\;}(E)\), where \({\rm acc\;}(E)\) is the set of all accumulation points of \(E\).

Proposition. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space, let \(E \subseteq X\), then \({\rm cl\;}(E)=E \cup {\rm acc\;}(E)\) and \(E\) is closed if \({\rm acc\;}(E) \subseteq E\).

Proof. (\(\Longrightarrow\)) If \(x \not\in {\rm cl\;}(E)\) then there is \(B(x,\varepsilon) \subseteq {\rm cl\;}(E)^c\), thus \(B(x,\varepsilon) \cap E=\varnothing\) hence \(x \not\in {\rm acc\;}(E)\). Thus \(E \cup {\rm acc\;}(E) \subseteq {\rm cl\;}(E)\).

(\(\Longleftarrow\)) If \(x \not\in E \cup {\rm acc\;}(E)\) there is an open \(U \ni x\) such that \(U \cap E=\varnothing\). Then \({\rm cl\;}(E) \subseteq U^c\) so \(x \not\in {\rm cl\;}(E)\) thus \({\rm cl\;}(E) \subseteq E \cap {\rm acc\;}(E)\).

Finally, E is closed iff \(E={\rm cl\;}(E)\) iff \({\rm acc\;}(E) \subseteq E\), since \[E={\rm cl\;}(E)=E \cup {\rm acc\;}(E) \quad \text{ as desired. } \quad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

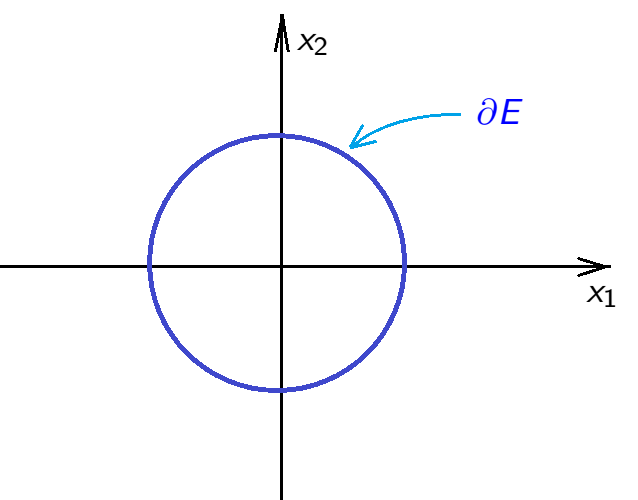

Boundary

Boundary of \(E\). The difference \({\rm cl\;}(E) \setminus {\rm int\;}(E)\) is called the boundary of \(E\) in a metric space \((X,\rho)\) and it is denoted by \(\partial E\).

Example 1. \(X=\mathbb{R}\) and \(-\infty<a<b<\infty\), \(E=(a,b)\), then \({\rm cl\;}(E)=[a,b]\), \({\rm int\;}(E)=(a,b)\), so \({\color{blue}\partial E=\{a,b\}}\).

Example 2. \(X=\mathbb{R}\), \(E=\mathbb{Z}\), then \({\rm int\;}(E)=\varnothing\), \({\rm cl\;}(\mathbb{Z})=\mathbb{Z}\), thus \({\color{blue}\partial \mathbb{Z}=\mathbb{Z}}\).

Example 3. \(X=\mathbb{R}\), \(E=\mathbb{Q}\), \({\rm cl\;}(E)=\mathbb{R}\), \({\rm int\;}(E)=\varnothing\), so \({\color{blue}\partial \mathbb{Q}=\mathbb{R}}\).

Boundary - examples

Example 4. \(X=\mathbb{R}^2\), \(\rho(x,y)=\sqrt{|x_1-y_1|^2+|x_2-y_2|^2}\), \(x=(x_1,x_2)\), \(y=(y_1,y_2)\), \[E=B(x,r)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;\rho(x,y)<r\},\]

\[{\rm cl\;}(E)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;\rho(x,y) \leq r\},\]

\[{\color{blue}\partial E=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\; \rho(x,y)=r\}}.\]

Boundary - example