8. Countable sets, cardinality continuum PDF

Countable sets

Countable set

Countable set. A set \(X\) is called countable (or denumerable) if \[{\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N}).\]

Example 1. In particular, finite sets are countable and for these sets it is convenient to interpret \({\rm card\;}(X)\) as the number of elements in \(X\):

\[{\rm card\;}(X)=n \iff {\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(\{1,2,\ldots,n\}).\]

Example 2. If \(X\) is countable but not finite, we say that \(X\) is countably infinite.

Countable sets - example

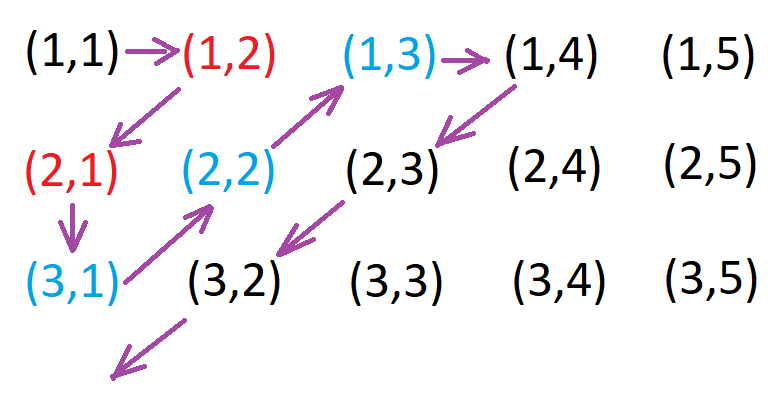

The set \(\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}\) is countable, i.e. \({\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\). Note that

can be listed as a sequence \[(1,1),{\color{red}(1,2),(2,1)},{\color{blue}(1,3),(2,2),(3,1)},{\color{brown}(1,4),(2,3),(3,2),(4,1)},{\color{purple}(5,1),(4,2)},\ldots\] establishing a bijection between \(\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}\) and \(\mathbb{N}\).

Proposition

Proposition.

If \(X\) and \(Y\) are countable, so is \(X \times Y\).

If \(A\) is countable and \(X_{\alpha}\) is countable for all \(\alpha \in A\), then \[\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \text{ is countable.}\]

If \(X\) is countably infinite then \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\).

Proof of (a). To prove (a) it suffices to show that \({\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\), but it was shown in the previous example.

Proof of (b). For each \(\alpha \in A\) there is a surjection \(f_{\alpha}:\mathbb{N\to X_{\alpha}}\) (here we have used the axiom of choice).

Then the map \(f:\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N} \to \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) defined by

\[f(n,\alpha)=f_{\alpha}(n)\] is surjective and we are done. Alternatively, to prove \[{\rm card\;}\left(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\right) \leq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N}),\] we can also proceed as follows \[X_1=\{x_{1,1},x_{1,2},x_{1,3},x_{1,4},\ldots\}\] \[{\color{red}X_2=\{x_{2,1},x_{2,2},x_{2,3},x_{2,4},\ldots\}}\] \[{\color{blue}X_3=\{x_{3,1},x_{3,2},x_{3,3},x_{3,4},\ldots\}}\] \[\cdots\] \[\bigcup_{j \in \mathbb{N}}X_j=\{x_{1,1},{\color{red}x_{1,2}},{\color{red}x_{2,1}},{\color{blue}x_{1,3}},{\color{blue}x_{2,2}},{\color{blue}x_{3,1}},\ldots\}.\]

Proof of (c).

We can assume that \(X\) is an infinite

subset of \(\mathbb{N}\).

Let \(f(1)\) be the smallest element of

\(X\) and define inductively \[f(n)=\min\big\{X \setminus

\{f(1),f(2),\ldots,f(n-1)\}\big\}.\]

Then it can be easily verified that \(f\) is a bijection from \(\mathbb{N}\) to \(X\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Corollaries

Corollary. \(\mathbb{Z}\) and \(\mathbb{Q}\) are countable.

Proof. \[\mathbb{Z}=\mathbb{N} \cup \{0\} \cup \{-n\;:\; n \in \mathbb{N}\},\]

Note that \[\mathbb{Q}=\bigcup_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\{\frac{m}{n}\;:\;m \in \mathbb{Z}\}.\]

Note also that \[{\rm card\;}(\mathbb{Q})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N} \cup \{0\})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{Z}).\]

Countable sets - example

Example. Prove that the following set is countable \[X=\{(n,m,k)\;:\; n,m,k \in \mathbb{N}\}.\]

Solution. Fix \(k \in \mathbb{N}\). It is clear that \[f(n,m)=(n,m,k)\] is a bijection between \(\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}\) and \(A_k=\{(n,m,k)\;:\; n,m \in \mathbb{N}\}\), so \(A_k\) is countable. Then we write \[X=\bigcup_{k \in \mathbb{N}}A_k\] and use the previous theorem.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Prove that the set \(\mathbb{Q} \times \mathbb{Q}\) is countable.

Solution. Fix \(q \in \mathbb{Q}\). It is easy to check that \(f(x)=(x,q)\) is bijection between \(\mathbb{Q}\) and \(A_q=\{(r,q)\;:\; r \in \mathbb{Q}\}\). Hence \(A_q\) is countable. We write \[\mathbb{Q} \times \mathbb{Q}=\bigcup_{q \in \mathbb{Q}}A_q\] and use the previous theorem.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proposition

Proposition. \(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}_0}\) is uncountable.

Proof. Suppose that the set \(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}_0}\) is countable, then \[\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}_0}=\{\alpha_0,\alpha_1,\alpha_2,\ldots\}.\]

\[\alpha_0: \ \ \ {\color{red}\alpha_0(0)}, \alpha_0(1), \alpha_0(2),\ldots\] \[\alpha_1: \ \ \ \alpha_1(0), {\color{red}\alpha_1(1)}, \alpha_1(2),\ldots\] \[\alpha_2: \ \ \ \alpha_2(0), \alpha_2(1), {\color{red}\alpha_2(2)},\ldots\] \[\ldots\]

consider a new sequence \(\Delta:\mathbb{N}_0 \to \{0,1\}\) defined by \(\Delta(n)=1-\alpha_n(n).\) Then \(\Delta \neq \alpha_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\), thus \(\Delta \not\in \{\alpha_n\;:\;n \in \mathbb{N}_0\}\), but \(\Delta \in \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}_0},\) contradiction.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cardinality continuum

Cardinality continuum

Cardinality continuum. A set \(X\) is said to have cardinality continuum if \[{\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R}).\]

We shall write \({\rm card\;}(X)=\mathfrak{c}\) iff \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R}).\)

Theorem. \[{\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{N}))={\rm card\;}(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R}).\]

We first show that \[{\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{N}))={\rm card\;}(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}).\]

Define \(F:P(\mathbb{N}) \to \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}\) by setting

\[F(A)=\chi_{A} \in \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}},\]. \[\chi_{A}(x)=\begin{cases} 1 \text{ if }x \in A,\\ 0 \text{ if }x\not\in A. \end{cases}\]

Example. If \(A=\{1,2,3,5,7,9\}\), then \(\chi_A\) can be identified with the sequence \[(\underbrace{1}_{{\color{red}1}},\underbrace{1}_{{\color{red}2}},\underbrace{1}_{{\color{red}3}},\underbrace{0}_{{\color{red}4}}, \underbrace{1}_{{\color{red}5}}, \underbrace{0}_{{\color{red}6}}, \underbrace{1}_{{\color{red}7}}, \underbrace{0}_{{\color{red}8}}, \underbrace{1}_{{\color{red}9}}, \underbrace{0}_{{\color{red}10}},\underbrace{0}_{{\color{red}11}},\ldots)\]

Our aim is to show that \(F\) is a bijection.

Let \(A,B \subseteq \mathbb{N}\) be such that \(A \neq B\), then we show that \(F(A) \neq F(B)\). Since \(A \neq B\) (wlog) there exists \(x_0 \in A \setminus B\), thus \[1=\chi_{A}(x_0) \neq \chi_{B}(x_0)=0 \quad \iff \quad F(A) \neq F(B),\] which proves that \(F:P(\mathbb{N}) \to \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}\) is injective.

To show that \(F\) is surjective take \(\alpha=(\alpha_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \in \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}\) and consider \[E=\{n \in \mathbb{N}\;:\;\alpha_n=1\}.\] then \[F(E)=\chi_E=\alpha \quad \iff \quad 1=\alpha_n=\chi_E(n)=1.\]

It remains to prove that \[{\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{N}))={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R}).\] We first show that \({\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{N})) \leq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R})\).

Definition. We will use the convention that \[\sum_{n \in A}a_n=\sup\left\{\sum_{n \in F}a_n\;:\; F \subseteq A \text{ and }F\text{ is finite}\right\}.\]

We now construct an injection \(f:P(\mathbb{N}_0) \to \mathbb{R}\) by setting

\[f(A)=\sum_{n \in A}\frac{2}{3^{n+1}}\quad \text{ for any } \quad A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0.\].

First we have to show that \(f\) is well defined, i.e. \(f(A)\) is finite for every \(A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0.\) Since \(f(A) \leq f(\mathbb{N}_0)\) for all \(A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0\) it suffices to show that

\[f(\mathbb{N}_0)\quad \text{ is finite}.\].

Let \([N]=\{0,1,2,\ldots,N\}\) and observe that \(f(\mathbb{N}_0)=\sup_{N \in \mathbb{N}_0}f([N])\). Moreover, one has \[\begin{aligned} f([N])=\sum_{n \in [N]}\frac{2}{3^{n+1}}=\frac{2}{3}\frac{1-\frac{1}{3^{N+1}}}{1-\frac{1}{3}}=1-\frac{1}{3^{N+1}} \leq 1. \end{aligned}\]

Geometric sequence. Here we have used the formula \({\color{blue}1+x+x^2+\ldots+x^N=\frac{1-x^{N+1}}{1-x}},\) which holds for all \(|x|<1\).

In fact, one can prove that \(f(\mathbb{N}_0)=1\) (check this!). Now we show that \(f:P(\mathbb{N}_0) \to \mathbb{R}\) is injective. Let \(A,B \subseteq \mathbb{N}\) be such that \(A \neq B\). Let \[n_0=\min\{n \in \mathbb{N}_0\colon \chi_A(n)\neq \chi_B(n)\}.\] Wlog we can assume \(n_0 \in B \setminus A\). Then \[\begin{aligned} f(A)&=\sum_{n \in A}\frac{2}{3^{n+1}}={\color{blue}\sum_{\substack{n \in A \\ n<n_0}}\frac{2}{3^{n+1}}} +\sum_{\substack{n \in A \\ n>n_0}}\frac{2}{3^{n+1}} \\ &\le {\color{blue}\sum_{\substack{n \in B\\ n<n_0}}\frac{2}{3^{n+1}}}+\sum_{n \in (n_0,\infty)}\frac{2}{3^{n+1}} \\ &< {\color{blue}\sum_{\substack{n \in B\\ n<n_0}}\frac{2}{3^{n+1}}}+\frac{2}{3^{n_0+1}} \leq f(B). \end{aligned}\]

We have used \(f((n_0,\infty) \cap \mathbb{N}_0)=\frac{1}{3^{n_0+1}}<\frac{2}{3^{n_0+1}}\) (check this!).

Hence \(f(A) \neq f(B)\) as desired, yielding \({\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{N}_0)) \leq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R})\).

Since \({\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N}_0)={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{Q})\) thus \({\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{N}_0))={\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{Q}))\). Now define \(g:\mathbb{R} \to P(\mathbb{Q})\) by \[g(x)=\{r \in \mathbb{Q}\colon r<x\} \quad \text{ for any } \quad x\in \mathbb{R}.\]

It is easy to see that \(g\) is injective, thus \[{\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R}) \leq {\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{Q}))={\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{N}_0)).\]

By the Cantor–Bernstein–Schröder theorem \[{\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R})={\rm card\;}(P(\mathbb{N}_0))={\rm card\;}(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}).\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Remarks

If \({\rm card\;}(X) \geq \mathfrak{c}\), then \(X\) is uncountable.

\({\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R})\).

\({\rm card\;}(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}_0} \times \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}_0})={\rm card\;}(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}_0})\).

\({\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R}^k)={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R})\) for any \(k\in \mathbb N\).

If \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq \mathfrak{c}\) and \({\rm card\;}(Y) \leq \mathfrak{c}\), then \({\rm card\;}(X \times Y) \leq \mathfrak{c}\).

If \({\rm card\;}(A) \leq \mathfrak{c}\) and \({\rm card\;}(X_{\alpha}) \leq \mathfrak{c}\) for any \(\alpha \in A\), then \[{\rm card\;}\left(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\right) \leq \mathfrak{c}.\]

Uncountable sets - example

Example. Prove that \({\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R})={\rm card\;}([0,1])\).

Solution. Define \(f:\mathbb{R} \to [0,1]\) by \[f(x)=\frac{x}{|x|+1}.\] One can verify that \(f\) is a bijection between \(\mathbb{R}\) and \([0,1]\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Determine \({\rm card\;}(X)\), where \(X\) is \[\{[n,n+1)\;:\;n \in \mathbb{N}\}.\]

Solution. We will prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\). Let us define the function \[f([n,n+1))=n.\] It is easy to verify that \(f\) is bijection between \(\mathbb{N}\) and \(X\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Determine \({\rm card\;}(X)\), where \(X\) is any infinite set of pairwise disjoint closed intervals.

Solution. We will prove that \(X\) is countably infinite. Let us define the function \(f:X \to \mathbb{Q}\) by setting \[f(I)=q,\] where \(q\) is any rational number contained in interval \(I \in X\). Then \(f\) is injective, so \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$