7. Axiom of Choice, Cardinality, Cantor's theorem PDF

Axiom of Choice

Set of maps

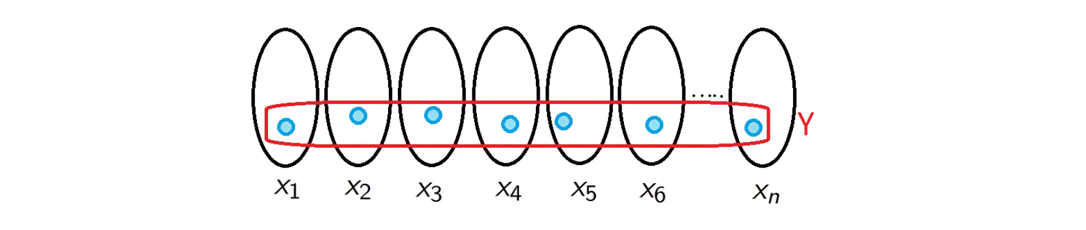

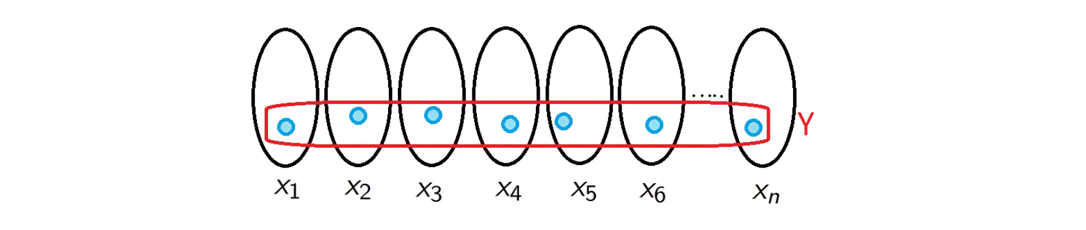

Cartesian product. If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is an indexed family of sets, their Cartesian product \[\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\] is the set of all maps \(f:A \to \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) so that \(f(\alpha)\in X_{\alpha}\) for all \(\alpha \in A\).

Projection map. If \(X=\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) and \(\alpha \in A\) we define \(\alpha\)-th projection or coordinate map \(\pi_{\alpha}:X \to X_{\alpha}\) by \(\pi_{\alpha}(f)=f(\alpha)\).

We will also write \(x=(x_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A} \in X=\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) instead of \(f\), and \(x_{\alpha}\) instead of \(f(\alpha)\).

Set of maps - examples 1/2

Example 1. If \(A=\{1,2,\ldots,n\}\), then \[\begin{aligned} X&=\prod_{j=1}^n X_j=X_1 \times X_2 \times \ldots \times X_n\\&=\{(x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_n)\;:\; x_j \in X_j \text{ for all }j=1,2,\ldots,n\}. \end{aligned}\]

Example 2. If \(A=\mathbb{N}\), then \[\begin{aligned} X&=\prod_{j=1}^\infty X_j=X_1 \times X_2 \times \ldots=\{(x_1,x_2,\ldots)\;:\; x_j \in X_j \text{ for all }j=1,2,\ldots\}. \end{aligned}\]

Set of maps - examples 2/2

Example 3. If the sets \(X_{\alpha}\) are all equal to some fixed set \(Y\), we denote \[X=\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}=Y^A.\]

\(Y^{A}\)-the set of all mappings from \(A\) to \(Y\).

Example 4. \(\mathbb{Z}^{\mathbb{N}}\) - the set of all

sequences of integers.

\(\mathbb{R}^{\mathbb{N}}\) - the set

of all sequences of real numbers.

The axiom of choice

The axiom of choice. If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a nonempty collection of nonempty sets, then \[\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing.\]

Corollary. If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a disjoint collection of nonempty sets there is a set (called the selector) \(Y \subseteq \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) such that \(Y \cap X_{\alpha}\) contains precisely one element for each \(\alpha \in A\).

Take \(f \in \prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing\). Define \[Y=f[A],\] then

\[Y \cap X_{\alpha}=\{f(\alpha)\},\] since \(f(\alpha) \in X_{\alpha}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cardinality

Cardinality

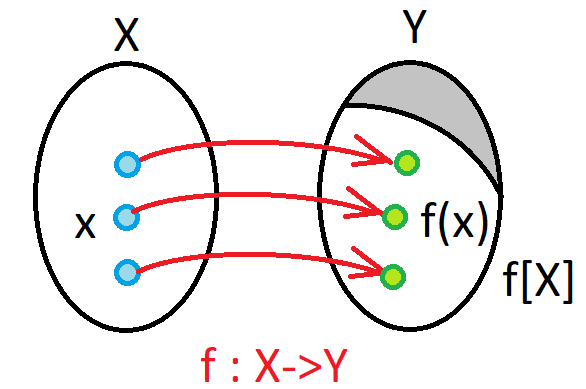

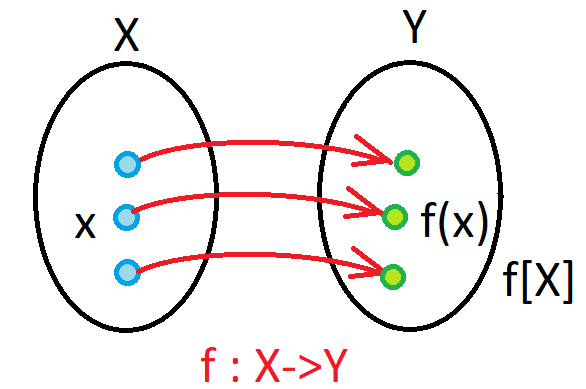

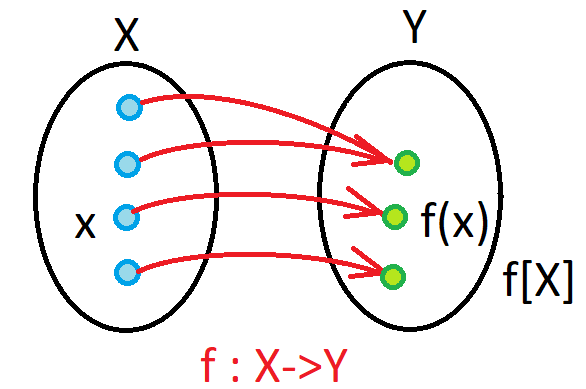

Cardinality. If \(X\) and \(Y\) are nonempty sets, we define the expressions \[{\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y) \ \ \text{ {\color{red}(injective)}},\] \[{\rm card\;}(X) = {\rm card\;}(Y)\ \ \text{ {\color{red}(bijective)}},\] \[{\rm card\;}(X) \geq {\rm card\;}(Y) \ \ \text{ {\color{red}(surjective)}},\]

to mean that there exists \(f:X \to Y\) which is injective, bijective, surjective respectively.

Cardinality - pictures 1/2

\({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y),\) (injective) ,.

\({\rm card\;}(X) = {\rm card\;}(Y),\) (bijective).

Cardinality - pictures 2/2

\({\rm card\;}(X) \geq {\rm card\;}(Y),\) (surjective).

We also define \({\rm card\;}(X)<{\rm card\;}(Y)\) to mean that there is an injection but not a bijection.

We also have \({\rm card\;}(\varnothing) < {\rm card\;}(X)\) and \({\rm card\;}(X)>{\rm card\;}(\varnothing)\) for all \(X \neq \varnothing\).

\({\rm card\;}(X)\) -example

Example. Let \[X=\{1,2,3,4,\ldots\}\] \[Y=\{101,102,103,\ldots,\}.\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution. Let us define \(f:X \to Y\) by \[f(x)=x+100,\] then \(f\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\({\rm card\;}(X)\) - example

Example. Let \[X=\{1,2,3,4,\ldots\}\] \[Y=\{1^2,2^2,3^2,4^2,\ldots,\}.\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution 1. Let us define \(f:X \to Y\) by \[f(x)=x^2,\] then \(f\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Solution 2. Let us define \(g: Y \to X\) by \[f(x)=\sqrt{x},\] then \(g\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Let \[X=\{1,2,3\}\] \[Y=\{2,4,6,8\}.\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)<{\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution. Note that \(f(x)=2x\) is an injection from \(X\) to \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y)\). On the other hand, any function from \(X\) to \(Y\) takes at most \(3\) values, so it is not a surjection, so \({\rm card\;}(X)<{\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Let \[X=[0,1]\] \[Y=[1,3].\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution. Let us define \(f:X \to Y\) by \[f(x)=2x+1,\] then \(f\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\), so \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proposition

Proposition. We have \[{\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y) \iff {\rm card\;}(Y) \geq {\rm card\;}(X).\]

Proof (\(\Rightarrow\)). Assume that \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y)\). This means that there is an injection \(f:X \to Y\). Thus \(f\) is a bijection \(f:X \to f[X] \subseteq Y\). Let \(f^{-1}\) be the inverse \(f^{-1}:f[X] \to X\). Pick \(x_0 \in X\) and define \(g\) by

\[g(y)=\begin{cases}f^{-1}(y) \text{ if }y \in f[X],\\ g(y)=x_0 \text{ if }y \in Y \setminus f[X]. \end{cases}\].

Then we see that \(g\) is surjective from \(Y\) to \(X\).

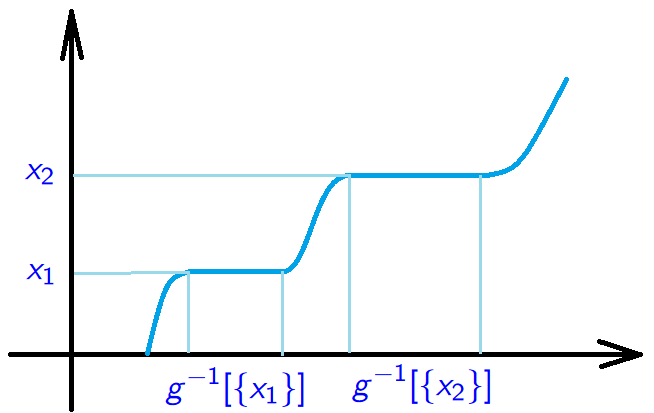

Proof (\(\Leftarrow\)). If \({\rm card\;}(Y) \geq {\rm card\;}(X)\), then there is a surjection \(g:Y \to X\). Then \(g[Y]=X\), and, consequently, \(g^{-1}[\{x\}]\) are nonempty and

\[g^{-1}[\{x_1\}] \cap g^{-1}[\{x_2\}] = \varnothing \quad\text{ if }\quad x_1 \neq x_2.\].

Using the axiom of choice the set \(\prod_{x \in X}g^{-1}[\{x\}] \neq \varnothing\). Taking \[f \in \prod_{x \in X}g^{-1}[\{x\}]\] we see that \(f\) is an injection from \(X\) to \(Y\). Indeed, if \(x_1 \neq x_2\), then \(f(x_1) \in g^{-1}[\{x_1\}]\) and \(f(x_2) \in g^{-1}[\{x_2\}]\), but \[g^{-1}[\{x_1\}] \cap g^{-1}[\{x_2\}] = \varnothing,\] thus \(f(x_1) \neq f(x_2)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\({\rm card\;}(X)\) - example

Example. Let \[X=[0,1],\] \[Y=\left\{\frac{1}{n}\;:\;n \in \mathbb{N}\right\}.\] Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X) \geq {\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution. One has \({\rm card\;}(Y) \leq {\rm card\;}(X)\). Indeed, define \(f:Y \to X\) by \[f(x)=x,\] which is injective, so \({\rm card\;}(X) \geq {\rm card\;}(Y)\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark. Actually we have \({\rm card\;}(X) > {\rm card\;}(Y)\), which will be proved later.

Banach lemma

Theorem. For any sets \(X\) and \(Y\) \[\text{ either }\quad {\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y)\quad \text{ or }\quad {\rm card\;}(Y) \leq {\rm card\;}(X).\]

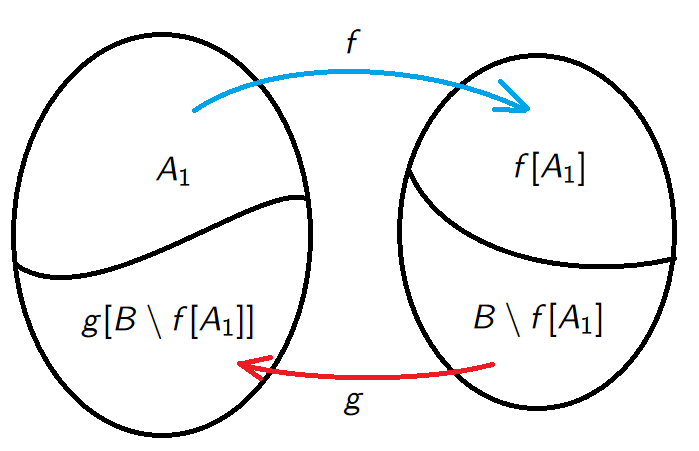

Banach lemma. Let \(f:A \to B\) and \(g:B \to A\) be injections. Then there are sets \(A_1,A_2,B_1,B_2\) such that

\(A_1 \cup A_2=A\) and \(A_1 \cap A_2 = \varnothing\),

\(B_1 \cup B_2=B\) and \(B_1 \cap B_2 = \varnothing\),

\(f[A_1]=B_1\) and \(f[A_2]=B_2\).

Banach lemma - picture

Consider the map \(\Phi:P(A) \to P(A)\) defined by \[\Phi(X)=A \setminus g[B \setminus f[X]] \quad \text{ for } \quad X \in P(X).\]

Since \(g\) is injective we note that \[\Phi\left[\bigcup_{t \in I}A_t\right]=\bigcup_{t \in I}\Phi[A_t]\] for any family \((A_t)_{t \in I}\) such that \(A_t \subseteq A\) for all \(t\in I\). Consider \[\Omega=\varnothing \cup \Phi[\varnothing] \cup \Phi \circ \Phi[\varnothing] \cup \ldots \cup \overbrace{\Phi \circ \Phi \circ \ldots \circ \Phi}^n[\varnothing] \cup \ldots,\] in other words \[\Omega=\bigcup_{n=0}^\infty \Phi^n[\varnothing].\]

Then \[\begin{aligned} \Phi[\Omega]=\bigcup_{n=0}^{\infty}\Phi^{n +1}[\varnothing] =\bigcup_{n=1}^{\infty}\Phi^{n}[\varnothing] =\left(\bigcup_{n=1}^{\infty}\Phi^{n}[\varnothing]\right) \cup \varnothing =\bigcup_{n=0}^{\infty}\Phi^{n}[\varnothing] =\Omega, \end{aligned}\] thus the set \(\Omega\) if a fixed point of \(\Phi\), i.e. \(\Phi[\Omega]=\Omega\). Taking \[A_1=\Omega, \ \ A_2=A \setminus A_1,\] \[B_1=f[A_1], \ \ B_2=B \setminus B_1\] we obtain

\[\begin{aligned} A_1=\Phi[A_1]=A \setminus g[B \setminus f[A_1]]=A \setminus g[B \setminus B_1]=A \setminus g[B_2], \end{aligned}\] thus \[\begin{aligned} A_2=A \setminus A_1=A \setminus (A \setminus g[B_2])=g[B_2]. \end{aligned}\]

Cantor–Bernstein–Schröder theorem (1.5.11)

Cantor–Bernstein–Schröder theorem. If \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y)\) and \({\rm card\;}(Y) \leq {\rm card\;}(X)\), then \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Proof. By Banach lemma there are \(A_1,A_2,B_1,B_2\) such that \[A_1 \cup A_2=X, \ \ f[A_1]=B_1, \ \ A_1 \cap A_2 =\varnothing\] \[B_1 \cup B_2=X, \ \ g[B_2]=A_2, \ \ B_1 \cap B_2 =\varnothing\] whenever \(f:X \to Y\) and \(g:Y \to X\) are injections. Define \(h:X \to Y\) by setting

\[h(x)=\begin{cases} f(x) &\text{ if }x \in A_1,\\ g^{-1}(x) &\text{ if }x \in A_2. \end{cases}\].

Then we see that \(h\) is a bijection between \(X\) and \(Y\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cantor–Bernstein–Schröder theorem - example

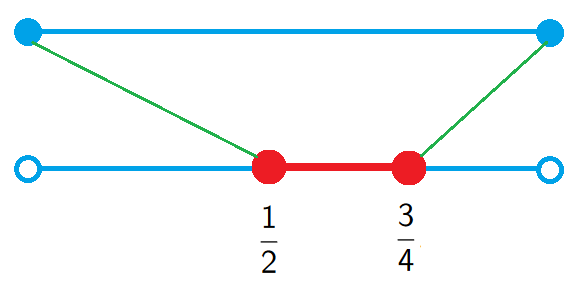

Example. Let \(X=[0,1], \ \ Y=(0,1).\) Prove that \({\rm card\;}(X) = {\rm card\;}(Y)\).

Solution. Note that \({\rm card\;}(Y) \leq {\rm card\;}(X)\), because \(f(x)=x\) is injective. Then, let us prove that \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(Y)\). We define \[g(x)=\frac{x}{4}+\frac{1}{2}.\] One can check that \(g\) is injective, so, by Cantor–Bernstein–Schröder theorem, \({\rm card\;}(X)={\rm card\;}(Y)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cantor’s theorem

Theorem (Cantor, Theorem 1.6.2). For any set \(X\) we have \({\rm card\;}(X) < {\rm card\;}(P(X))\).

Proof. The map \(f:X \to P(X)\) defined by \(f(x)=\{x\}\) is an injection from \(X\) to \(P(X)\). Thus \({\rm card\;}(X) \leq {\rm card\;}(P(X))\).

We now show that there is no bijection between \(X\) and \(P(X)\). Let \(g:X \to P(X)\) and consider the set \[{\color{red}Y=\{x \in X\;:\; x \not\in g(x)\}} \in P(X).\] Then we claim that \(Y \not\in g[X]\).

If \[Y=\{x \in X\;:\; x \not\in g(x)\} \in g[X],\] then there is \(x_0 \in X\) so that \({\color{blue}g(x_0)=Y}\).

On the one hand \[x_0 \in Y \iff {\color{red} x_0 \not\in g(x_0).}\]

On the other hand \[x_0 \in Y \iff {\color{blue}x_0 \in g(x_0)}.\]

Thus \[x_0 \in g(x_0) \iff x_0 \not\in g(x_0),\] which is impossible, and we conclude \({\rm card\;}(X)<{\rm card\;}(P(X))\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$