3. Least Upper Bounds and Greatest Lower Bounds; Axiom of Completeness, and; Construction of $\mathbb{R}$ from $\mathbb{Q}$ PDF

Ordered sets

Order on set

Order. Let \(S\) be a set. The order on \(S\) is the relation, denoted by \(<\), with the following properties:

If \(x,y \in S\), then one and only one of the following statements is true:

\(x<y\),

\(y<x\) (equivalently \(x>y\)),

\(x=y\).

If \(x,y,z \in S\), \(x<y\) and \(y<z\), then \(x<z\).

Notation: \(x \leq y\) means (\(x=y\) or \(x<y\)). Equivalently, \(x \leq y\) is the negation of \(x>y\).

Ordered set

Ordered set. Ordered set is the set \(S\) on which the order is defined.

Example. The set of rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\) is ordered set if \(<\) is the usual order on numbers. We say that \(r<s\) for \(r, s\in\mathbb Q\) iff \(s-r>0\).

Upper and lower bound

Upper bound. Suppose that \(S\) is an ordered set and \(E \subseteq S\). If there is \(\beta \in S\) such that \(\alpha \leq \beta\) for all \(\alpha \in E\), then \(E\) is bounded above and \(\beta\) is called the upper bound of \(E\).

Lower bound. Suppose that \(S\) is an ordered set and \(E \subseteq S\). If there is \(\beta \in S\) such that \(\beta \leq \alpha\) for all \(\alpha \in E\), then \(E\) is bounded below and \(\beta\) is called the lower bound of \(E\).

\(\sup E\)

\(\sup E\). Suppose that \(S\) is an ordered set, \(E \subset S\), and \(E\) is bounded from above. Suppose that there exists \(\alpha \in S\) with the following properties

\(\alpha\) is a upper bound of \(E\),

if \(\gamma<\alpha\), then \(\gamma\) is not an upper bound of \(E\) (equivalently, there is \(x \in E\) such that \(\gamma<x \leq \alpha\)).

Then \(\alpha\) is called a least upper bound or supremum of \(E\). We write \[\alpha=\sup E.\]

\(\inf E\)

\(\inf E\). Suppose that \(S\) is an ordered set, \(E \subset S\), and \(E\) is bounded from below. Suppose that there exists \(\alpha \in S\) with the following properties

\(\alpha\) is a lower bound of \(E\),

if \(\gamma>\alpha\), then \(\gamma\) is not a lower bound of \(E\) (equivalently, there is \(x \in E\) such that \(\alpha \leq x <\gamma\)).

Then \(\alpha\) is called the greatest lower bound or infimum of \(E\). We write \[\alpha=\inf E.\]

Examples

Example 1. Let \[A=\{p \in \mathbb{Q}\;:\;p>0,\; p^2<2\},\] \[B=\{p \in \mathbb{Q}\;:\;p>0,\; p^2>2\}.\] The set \(A\) is bounded from above. In fact, the upper bounds of \(A\) are exactly the members of \(B\). Since \(B\) contains no smallest member, it has no least upper bound in \(\mathbb{Q}\).

Example 2. Let \[E=\left\{\frac{1}{n}\;:\; n \in \mathbb{N}\right\}.\] Then \(\sup E=1\) and \(1 \in E\), \(\inf E=0\) and \(0 \not\in E\).

Axiom of completeness

Least–upper–bound property

Least–upper–bound property. An ordered set \(S\) is said to have least–upper–bound property if the supremum \(\sup E\) exists in \(S\) for all nonempty subsets \(E \subseteq S\) that are bounded above.

Example 1. Let \[A=\{p \in \mathbb{Q}\;:\;p>0,\; p^2<2\}.\] The previous slide shows that \(\mathbb{Q}\) has not least–upper–bound property.

Theorem

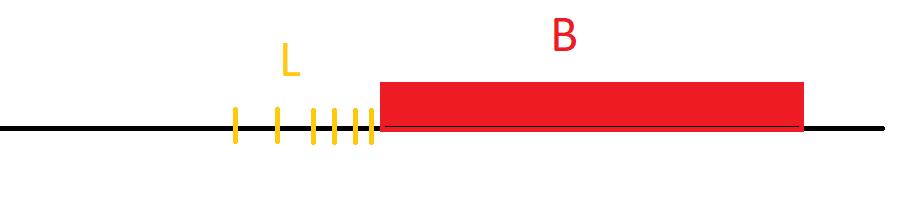

Theorem. Suppose that \(S\) is an ordered set with the least–upper–bound property. Let \(\varnothing\neq B \subseteq S\) be bounded below. Let \(L\) be the set of all lower bounds of \(B\). Then \(\alpha=\sup L\) exists in \(S\) and \(\alpha=\inf B\).

Proof. Let \[L=\{y \in S\colon y \leq x \text{ for all }x \in B\}.\]

We see that \(L \neq \varnothing\),

since \(B\) is bounded below. Every

\(x \in B\) is an upper bound of \(L\). Thus \(L\) is bounded above and consequently the

least–upper–bound property implies that \(\alpha=\sup L\) exists in \(S\).

We show that \(\alpha \in

L\). It suffices to prove that \(\alpha \leq x\) for all \(x \in B\). Suppose for a contradiction that

there is \(\gamma\in B\) such that

\(\gamma< \alpha\). By the

definition of supremum \(\gamma\) is

not an upper bound. Therefore, there exists \(y \in L\) such that \(\gamma<y\leq \alpha\), so \(y \leq x\) for every \(x \in B\), and hence \(\gamma<x\) for all \(x \in B\). In particular, we obtain \(\gamma<\gamma\) since \(\gamma\in B\), which is

impossible!

Now we show that \(\alpha=\inf B\). We have shown that \(\alpha \in L\), which means that \(\alpha\) is a lower bound of \(B\), since \(\alpha\le x\) for all \(x\in B\). If \(\alpha < \beta\), then \(\beta \not\in L\) since \(\alpha\) is an upper bound of \(L\). If \(\beta\not\in L\) then there exists \(x\in B\) such that \(\beta> x\ge \alpha\). This proves that \(\alpha=\inf B\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(\sup E\) and \(\inf E\) - example

Example. Find \(\sup E\) and \(\inf E\), where \[E=\left\{(-1)^n:n \in \mathbb{N}_0\right\}.\]

Solution. We have \((-1)^n=1\) for even \(n\) and \((-1)^n=-1\) for odd \(n\). Hence \[E=\{-1,1\}\] \[\begin{aligned} \sup E&=\max E=1,\\ \inf E&=\min E=-1. \end{aligned}\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Find \(\sup E\) and \(\inf E\), where \[E=\left\{\frac{1}{n^2+1}: n \in \mathbb{N}_0\right\}.\]

Solution. Note that for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\) we have \[\frac{1}{n^2+1} \leq \frac{1}{1}\] and for \(n=0\) we have \(\frac{1}{n^2+1}=\frac{1}{1}\). Hence \(\sup E=1\).

On the other hand, \(\frac{1}{n^2+1}>0\) for all \(n\in \mathbb{N}_0\) and \(\frac{1}{n^2+1}\) is small for large \(n\) ( it will be formalized later). Hence \(\inf E=0 \not\in E\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Find \(\sup E\) and \(\inf E\), where \[E=\left\{\frac{nm}{n^2+m^2}:n,m \in \mathbb{N}\right\}.\]

Solution. Note that \(\frac{nm}{n^2+m^2}>0\) and for \(m=1\) we have \[\frac{nm}{n^2+m^2}=\frac{n}{1+n^2}<\frac{1}{n}.\] Hence \(\inf E=0\). On the other hand, for all \(m,n\in \mathbb{N}\) we have \[\frac{mn}{m^2+n^2} \leq \frac{1}{2} \iff 2nm \leq m^2+n^2 \iff 0 \leq (m-n)^2,\] so \(\frac{mn}{m^2+n^2}\leq \frac{1}{2}\) for all \(m,n\in \mathbb{N}\). Moreover, \(\frac{mn}{m^2+n^2}=\frac{1}{2}\) for \(n=m=1\). Hence \(\sup E=\frac{1}{2}\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Fields

Field 1/2

Field. A field \(\mathbb{F}\) is a set with two operations called addition (\(+\)) and multiplication (\((\; \cdot\; )\) or without symbol), which satisfies the following field axioms (A), (M), and (D).

Addition axioms (A).

(A1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\), then \(x+y \in \mathbb{F}\),

(A2) addition is commutative, i.e. \(x+y=y+x\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\),

(A3) addition is associative, i.e. \((x+y)+z=x+(y+z)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{F}\),

(A4) \(\mathbb{F}\) contains the element \(0\) such that \(x+0=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{F}\),

(A5) to every \(x \in \mathbb{F}\) corresponds an element \((-x) \in \mathbb{F}\) such that \[x+(-x)=0.\]

Field 2/2

Multiplication axioms (M).

(M1) if \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\), then their product \(xy \in \mathbb{F}\),

(M2) multiplication is commutative, i.e. \(xy=yx\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\),

(M3) addition is associative, i.e. \((xy)z=x(yz)\) for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{F}\),

(M4) \(\mathbb{F}\) contains the element \(1\neq0\) such that \(1x=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{F}\),

(M5) if \(x \in \mathbb{F}\) and \(x\neq0\) then there exists an element \(\frac{1}{x} \in \mathbb{F}\) such that \[x \cdot \frac{1}{x}=1.\]

Distributive law (D).

(D1) \(x(y+z)=xy+xz\) holds for all \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{F}\).

Field properties - addition

Example 1. \(\mathbb{Q}\) is a field.

Example 2. \(\mathbb{Z}\) is not a field, because (M5) does not hold, i.e. there is no \(x \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(2x=1\).

Properties of addition. The axioms of addition imply the following:

if \(x+y=x+z\), then \(y=z\),

if \(x=x+y\), then \(y=0\),

if \(x+y=0\), then \(y=(-x)\),

\((-(-x))=x\).

Proof of (A). \[\begin{aligned} y&\overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A4)} 0+y \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A5)} (-x+x)+y \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A3)} -x+(x+y)\\& \ =-x+(x+z) \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A3)} (-x+x)+z \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A5)} 0+z \overbrace{=}^{\color{red}(A4)} z. \end{aligned}\]

To prove (B), we take \(z=0\) in

(A).

To prove (C) we take \(z=-x\) in

(A).

Since \(x+(-x)=0\), so by (C) with \(-x\) in place of \(x\) we get \[(-(-x))=x.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Field properties - multiplication

Properties of multiplication. The axioms of multiplication imply the following:

if \(x \neq 0\) and \(xy=xz\), then \(y=z\),

if \(x \neq 0\) and \(x=xy\), then \(y=1\),

if \(x \neq 0\) and \(xy=1\), then \(y=\frac{1}{x}\),

if \(x \neq 0\), then \(\frac{1}{\frac{1}{x}}=x\)

Exercise.

Further field properties

Properties of fields. The field axioms imply the following:

\(x \cdot 0=0\) for all \(x\in \mathbb{F}\),

if \(x \neq 0\) and \(y \neq 0\), then \(xy\neq 0\),

\((-x)y=-(xy)=x(-y)\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\),

\((-x)(-y)=xy\) for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{F}\).

For the proof of (A), we use (D1): \[0x+0x\overbrace{=}^{{\color{brown}(D1)}}(0+0)x=0x.\] Thus we must have \(0x=0\).

To prove (B) assume \(x,y \neq 0\), but \(xy=0\). Then \[1=\frac{1}{x}\frac{1}{y}xy=\frac{1}{x}\frac{1}{y}0=0,\] but \(0 \neq 1\).

To prove (C) we write \[(-x)y+xy\overbrace{=}^{{\color{brown}(D1)}}(-x+x)y=0y=0,\] thus \((-x)y=-(xy)\).

To prove \((D)\) we use \((C)\) and we write \[(-x)(-y)=-(x(-y))=-(-(xy))=xy.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Ordered field

Ordered field. An ordered field is a field with is also an ordered set such that

if \(x,y,z \in \mathbb{F}\) and \(y<z\), then \(x+y<x+z\),

\(xy>0\) if \(x>0\) and \(y>0\).

Positive element. The element \(x \in \mathbb{F}\) is called positive if \(x>0\).

Negative element. The element \(x \in \mathbb{F}\) is called negative if \(x<0\).

Example. \(\mathbb{Q}\) is an ordered field.

Properties of ordered fields

Proposition. The following are true in every ordered field:

if \(x>0\), then \(-x<0\) and vice versa,

if \(x>0\) and \(y<z\), then \(xy<xz\),

if \(x<0\) and \(y<z\), then \(xy>xz\),

if \(x \neq 0\), then \(x \cdot x=x^2>0\). In particular, \(1>0\),

if \(0<x<y\), then \(0<\frac{1}{y}<\frac{1}{x}\).

Proof of (A). If \(x>0\), then \(0=-x+x>-x+0\), thus \(-x<0\). If \(x<0\), then \(0=-x+x<-x+0\), so that \(-x>0\).

Proof of (B). Since \(z>y\) we have \(z-y>y-y=0\), hence \(x(z-y)>0\) if \(x>0\). Thus \[xz=x(z-y)+xy>0+xy=xy.\]

Proof of (C). By (A),(B), and \((-x)y=-(xy)=x(-y)\): \[-(x(z-y))=(-x)(z-y)>0\] so that \(x(z-y)<0\) hence \(xz<xy\).

Proof of (D). If \(x>0\) we get \(x^2>0\). If \(x<0\), then \(-x>0\), hence \((-x)^2>0\), but \(x^2=(-x)^2\). We also see \(1^2=1\), thus \(1>0\).

Proof of (E). If \(y>0\) and \(v \leq 0\), then \(yv \leq 0\). But \(\frac{1}{y}\cdot y=1>0\), thus \(\frac{1}{y}>0\). In similar way \(\frac{1}{x}>0\). Multiplying the inequality \(x<y\) by \(\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\left(\frac{1}{y}\right)\) we have \[0<\frac{1}{y}<\frac{1}{x}.\]

$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The real field

Subfield. We say \(A\) is subfield of \(B\) if \(A\) is a field and every element of \(A\) belongs to \(B\).

Theorem. There exists an ordered field which has the least-upper-bound property and contains \(\mathbb{Q}\) as a subfield. It will be called the real field and denoted by \(\mathbb{R}\).

Axiom of completeness

Axiom of completeness

We will say that the set of real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\) satisfies axiom of completeness.

Axiom of completeness. Every non-empty set \(E\) of real numbers \(\mathbb R\) that is bounded above has a least upper bound. In other words, \(\sup E\) exists in \(\mathbb R\).