1. Numbers, sets, and induction PDF

Operations on sets

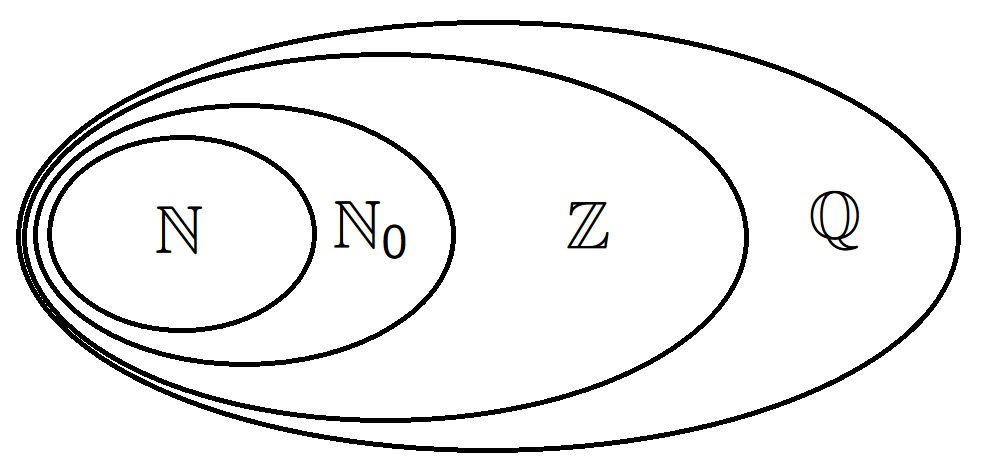

Number systems

\(\mathbb{N}=\{1,2,3,\ldots\}\)

-

positive integers,

\(\mathbb{N}_0=\{0,1,2,3,\ldots\}\) -

non-negative integers,

\(\mathbb{Z}=\{\ldots,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,\ldots\}\)

- the set of integers,

\(\mathbb{Q}=\{\frac{m}{n}, \,m \in

\mathbb{Z}, n \in \mathbb{Z} \setminus \{0\}\}\) - the set of

rationals.

Sets

The words family and collection will be used synonymously with "set".

Notation. \(\varnothing\)

- empty set,

\(\mathcal{P}(X)\) - family of subsets

of the set \(X\), sometimes called

power set of \(X\).

Example 1. If \(X=\{1\}\), then \[\mathcal{P}(X)=\{\varnothing, \{1\}\}.\]

Example 2. If \(X=\{1,2,3\}\), then \[\mathcal{P}(X)=\{\varnothing,\{1\},\{2\},\{3\},\{1,2\},\{1,3\},\{2,3\},\{1,2,3\}\}.\]

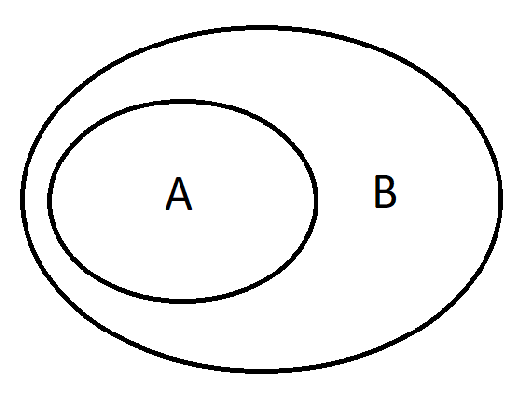

Inclusions 1/2

We write \(A \subseteq B\) if any element of \(A\) is also the element of \(B\).

We will write \(A \subset B\) if \(A \subseteq B\) and \(A \neq B\).

Inclusions 2/2

Example 1. If \(A=\{1,2\}\) and \(B=\{1,2,3\}\), then \(A \subseteq B\) and \(A \subset B\).

Example 2. If \(A=\{1,2,4\}\) and \(B=\{1,2,3\}\), then \(A \subseteq B\) does not hold, because \(4\) belongs to \(A\), but it does not belong to \(B\).

Union of sets 1/2

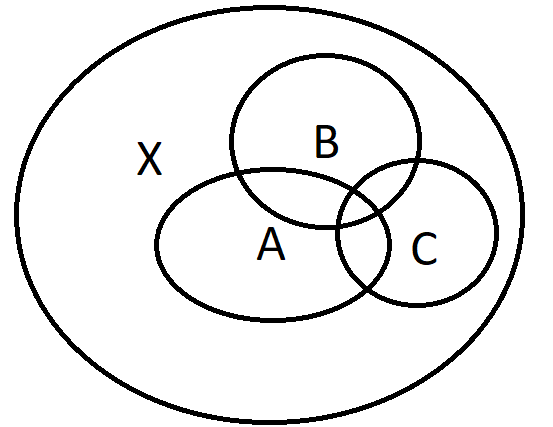

Union of sets. Let \(X\) be a set, \(\Sigma\) be a family of sets from \(\mathcal{P}(X)\). The union of the members from \(\Sigma\) is the following subset of \(X\): \[\bigcup_{E \in \Sigma}E=\{x \in X\;:\; x \in E \text{ for some }E \in \Sigma\}=\{x \in X\;:\; \exists_{E \in \Sigma} x \in E\}.\]

\(\exists \equiv\) there exists.

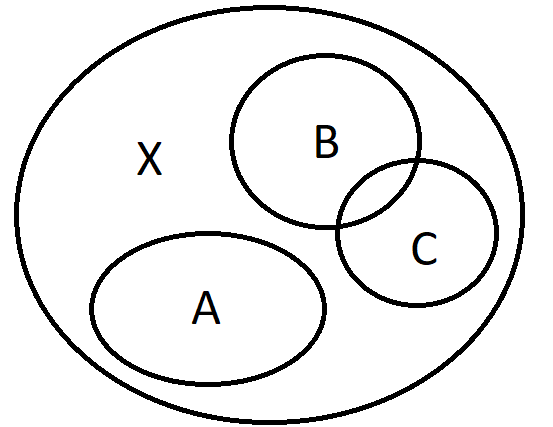

Union of sets 2/2

Example. If \(\Sigma=\{A,B,C\}\), then \(\bigcup_{E \in \Sigma}E=A \cup B \cup C\)

Intersection of sets 1/3

Intersection of sets. Let \(X\) be a set, \(\Sigma\neq\varnothing\) be a family of sets from \(\mathcal{P}(X)\). The intersection of the members from \(\Sigma\) is the following subset of \(X\): \[\bigcap_{E \in \Sigma}E=\{x \in X\;:\; x \in E \text{ for all }E \in \Sigma\}=\{x \in X\;:\; \forall_{E \in \Sigma} x \in E\}.\]

\(\forall \equiv\) for all.

Intersection of sets 2/3

Example 1. If \(\Sigma=\{A,B,C\}\), then \(\bigcap_{E \in \Sigma}E=A \cap B \cap C\)

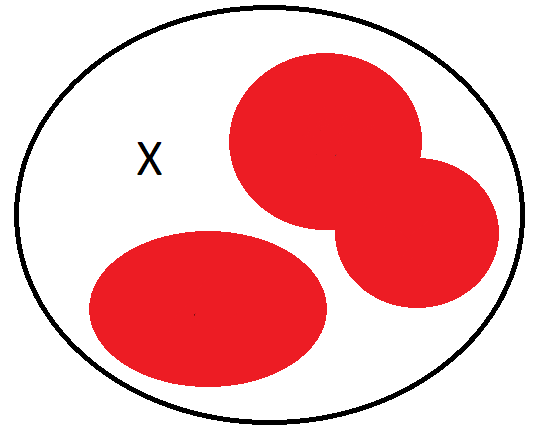

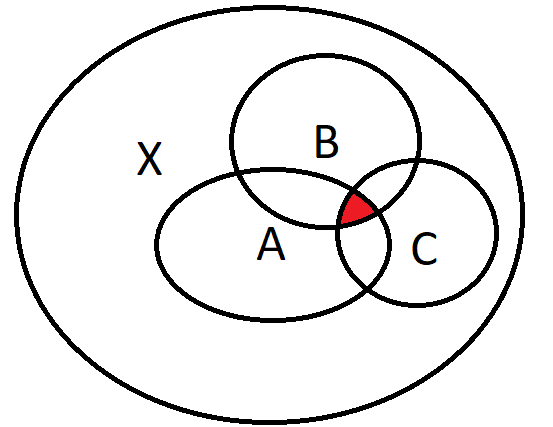

Intersection of sets 3/3

Example 2. If \(\Sigma=\{A,B,C\}\) as in the picture, then \(\bigcap_{E \in \Sigma}E=A \cap B \cap C=\varnothing\).

Union and intersection of indexed family of sets

If \(\Sigma=\{E_{\alpha}: \;\alpha \in A\}\), then the union and the intersection will be denoted respectively by

\[\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha} \text{ and }\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}.\].

Example 1. If \(A=\{1,2,3\}\), then \(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}=E_1 \cup E_2 \cup E_3\).

Example 2. If \(A=\mathbb{N}\), then \(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}=E_1 \cup E_2 \cup E_3 \cup E_4 \cup \ldots\).

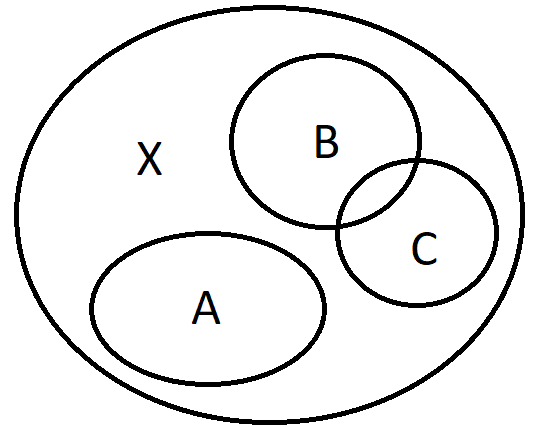

Disjointness

If \(A \cap B=\varnothing\), then we say that \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint.

Example. If \(A=\{1,2\}\), \(B=\{3,4\}\), \(C=\{1,2,3\}\), then \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint, but \(A\) and \(C\) are not disjoint.

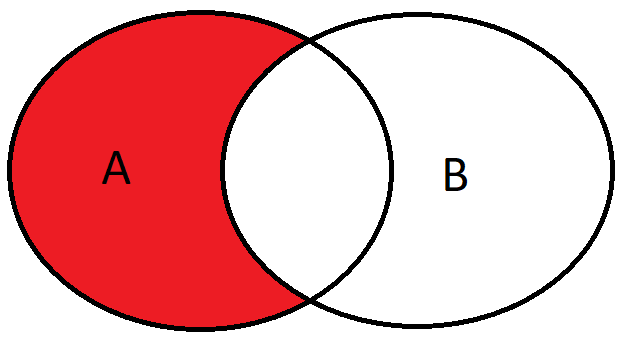

Difference of sets

Difference of sets. If \(A,B\) are two sets, then \[A \setminus B=\{x \in A\;:\;x \not\in B\}.\]

Example 1. If \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) and \(B=\{3\}\), then \(A \setminus B=\{1,2\}\).

Example 2. If \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) and \(B=\{4\}\), then \(A \setminus B=\{1,2,3\}\).

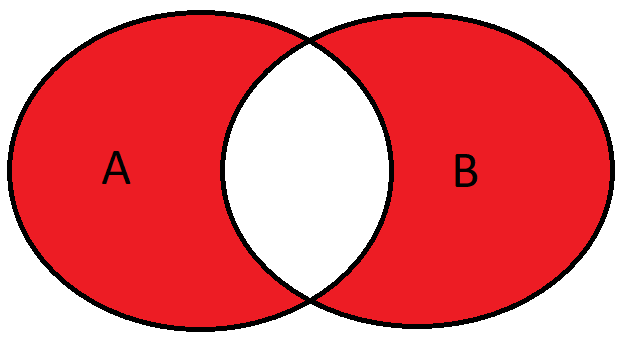

Symmetric difference of sets

Symmetric difference of sets. If \(A,B\) are two sets, then \[A \triangle B=(A \setminus B) \cup (B \setminus A)=(A \cup B) \setminus (A \cap B).\]

Example. If \(A=\{1,2,3,4\}\) and \(B=\{3,4,5,6\}\), then \(A \triangle B=\{1,2,5,6\}\).

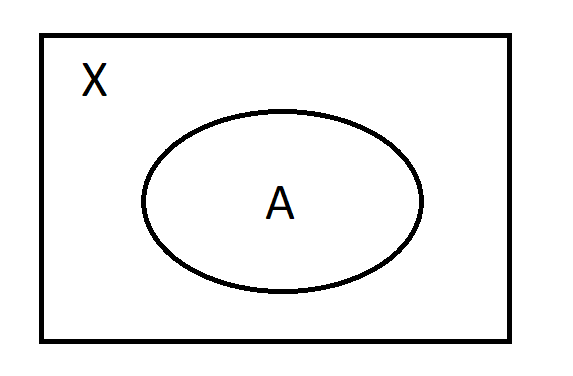

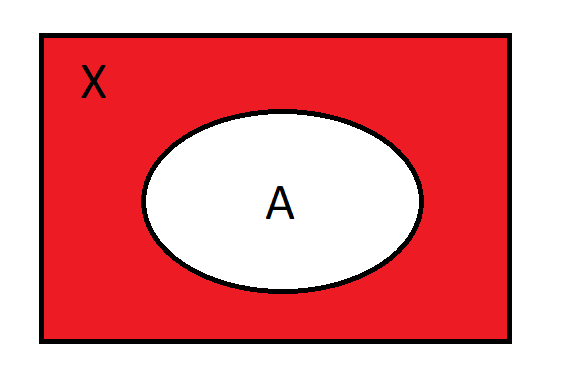

Complement of sets

Complement of sets. If a set \(X\) is given, and \(A \subseteq X\), then the complement of \(A\) in \(X\) is defined by \(A^c=X \setminus A\).

de Morgan’s laws

de Morgan’s laws. \[\left(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}\right)^c=\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}^c\] \[\left(\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}\right)^c=\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}E_{\alpha}^c\]

Example. We have \((A \cup B)^c=A^c \cap B^c\) and \((A \cap B)^c=A^c \cup B^c\).

The principle of induction

Well-ordering principle

Well-ordering principle. If \(A\) is a non-empty subset of non-negative integers \(\mathbb N_0\), then \(A\) contains the smallest number.

Example 1. If \(A=\{65,43,21\}\), then the smallest element is \(21\).

Example 2. If \(A\) is the set of even numbers, then the smallest element is \(0\).

Induction principle

The principle of induction. If \(A\) is a set of non-negative integers such that

(Base step): \(0 \in A\)

(Induction step): Whenever \(A\) contains a number \(n\), it also contains the number \(n+1\).

Then \(A=\mathbb{N}_0\).

\[\forall_{A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0}\left(0 \in A \text{ and }\forall_{k \in \mathbb{N}}(k \in A \Longrightarrow (k+1) \in A) \text{ then }A=\mathbb{N}_0\right)\]

The maximum principle

Subset bounded from above. We say that \(A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0\) is bounded from above if there is \(M \in \mathbb{N}_0\) such that \(a \leq M\) for all \(a \in A\).

\[\exists_{M \in \mathbb{N}_0} \ \ \forall_{a \in A} \ \ a \leq M\]

The maximum principle. A non-empty subset of \(\mathbb{N}_0\), which is bounded from above contains the greatest number.

Induction principle - example

Exercise. Prove that for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\) we have \[\label{eq:n} \sum_{k=0}^{n}k=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}.\]

Solution. Let \(A\) be the set of \(n\) for which [eq:n] holds. \[A=\left\{n \in \mathbb{N}_0\;:\; \sum_{k=0}^{n}k=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right\}\] Our goal is to show that \(A = \mathbb{N}_0\). We will use the induction principle. We have to check the base step and the induction step.

Induction principle - example (base step)

Exercise. Prove that for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\) we have \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}k=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}.\]

Let us check if \(0 \in A\). We have \[\sum_{k=0}^0 k = 0 =\frac{0(0+1)}{2},\] so \(0 \in A\).

Induction principle - example (induction step 1/2)

Exercise. Prove that for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\) we have \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}k=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}.\]

Let us check that whenever \(n \in A\), then \(n+1 \in A\). If \(n \in A\), then \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}k=1+2+3+\ldots+(n-1)+n=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}.\]

Our goal is to prove that \(n+1 \in A\), i.e., \[\sum_{k=0}^{n+1}k=1+2+3+\ldots+(n-1)+n+(n+1)=\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2}.\]

Induction principle - example (induction step 2/2)

Exercise. Prove that for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_0\) we have \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}k=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}.\]

We calculate \[\begin{split} &\sum_{k=0}^{n+1}k=1+2+3+\ldots+(n-1)+n+(n+1)\\&={\color{blue}1+2+3+\ldots+(n-1)+n}+{\color{red}(n+1)}\\&={\color{blue}\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}+{\color{red}(n+1)}\\&=\frac{n^2+n}{2}+\frac{2n+2}{2}=\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2}. \end{split}\]