20. Continuity, compactness and connectivity; Uniform continuity; Sets of Discontinuity PDF

Continuity compactness and connectivity

Continuity and compactness

Bounded function. A mapping \(f:E \to \mathbb{R}\) is said to be bounded if there is a number \(M>0\) such that \[|f(x)| \leq M\quad \text{ for all }\quad x \in E.\]

Theorem. Suppose that \(f: X\to \mathbb R\) is a continuous function and \(X\subseteq \mathbb R\) is compact. Then \(f[X]\) is compact in \(\mathbb R\).

Let \((V_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) be an open cover of \(f[X]\), i.e. \[f[X] \subseteq \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}V_{\alpha}.\] Since \(f\) is continuous then each set \(f^{-1}[V_{\alpha}]\) is open in \(X\). Since \(X\) is compact and \[X \subseteq \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}f^{-1}[V_{\alpha}]\] thus there are \(\alpha_1,\alpha_2,\ldots,\alpha_n \in A\) so that \[X \subseteq \bigcup_{j=1}^n f^{-1}[V_{\alpha_j}].\] Since \(f[f^{-1}[E]] \subseteq E\) we have \[f[X] \subseteq f\big[\bigcup_{j=1}^{n}f^{-1}[V_{\alpha_j}]\big] \subseteq \bigcup_{j=1}^{n}V_{\alpha_j}. \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Corollary

Corollary. If \(f:X \to \mathbb{R}\) is continuous on a compact set \(X\subseteq \mathbb R\) then \(f[X]\) is closed and bounded in \(\mathbb{R}\). Specifically, \(f\) is bounded.

Theorem. Suppose \(f:X \to \mathbb{R}\) is continuous on a compact set \(X\subseteq \mathbb R\) and \[M=\sup_{p \in X}f(p)\quad \text{ and }\quad m=\inf_{p \in X}f(p).\] Then there are \(p,q\in X\) such that \[f(p)=M \quad \text{ and }\quad f(q)=m.\]

Proof. \(f[X] \subseteq \mathbb{R}\) is closed and bounded. Thus \(M\) and \(m\) are members of \(f[X]\) and we are done. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem

Theorem. Suppose \(f\) is continuous injective mapping of a compact set \(X\subseteq \mathbb R\) onto a set \(Y\subseteq \mathbb R\). Then the inverse mapping \(f^{-1}\) defined on \(Y\) by \[f^{-1}(f(x))=x, \ \ \ x \in X\] is a continuous mapping of \(Y\) onto \(X\).

Proof. The inverse \(f^{-1}:Y \to X\) is well defined since \(f:X \to Y\) is one-to-one and onto. It suffices to prove that \(f[V]\) is open in \(Y\) for every open set \(V\) in \(X\). Fix \(V \subseteq X\) open, \(V^c\) is closed in \(X\) thus compact, hence \(f[V^c]\) is compact subset of \(Y\) and consequently \(f[V^c]\) is closed. Since \(f:X \to Y\) is one-to-one and onto, hence \[f[V]=\left(f[V^c]\right)^c\] and, consequently, \(f[V]\) is open as desired.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Continuity and connectivity

Theorem. If \(f:\mathbb R \to \mathbb R\) is a continuous function and if \(E\) is a connected subset of \(\mathbb R\) then \(f[E]\) is connected in \(\mathbb R\).

Proof. Assume for a contradiction that \(f[E]=A \cup B\), where \(A\) and \(B\) are nonempty separated sets in \(\mathbb R\). Put \[G=E \cap f^{-1}[A] \quad \text{ and }\quad H=E \cap f^{-1}[B].\]

Then \(E=G \cup H\) and neither \(G\) nor \(H\) is empty.

Since \(A \subseteq {\rm cl\;}(A)\) we have \(G \subseteq f^{-1}[{\rm cl\;}(A)]\) and the latter set is closed since \(f\) is continuous hence \({\rm cl\;}(G) \subseteq f^{-1}[{\rm cl\;}(A)]\).

Hence \[f[{\rm cl\;}(G)] \subseteq f[f^{-1}[{\rm cl\;}(A)]] \subseteq {\rm cl\;}(A).\]

Since \(f[H] \subseteq B\) and \({\rm cl\;}(A) \cap B = \varnothing\) we conclude that \[f[H \cap {\rm cl\;}(G)] \subseteq f[{\rm cl\;}(G)] \cap f[H] \subseteq {\rm cl\;}(A) \cap B=\varnothing,\] so \(H \cap {\rm cl\;}(G)=\varnothing\).

The same argument shows that \({\rm cl\;}(G) \cap H=\varnothing\).

Thus \(G\) and \(H\) are separated sets, which is a contradiction since \(E\) is connected.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Darboux property

Darboux property (intermediate value theorem). Let \(f\) be a continuous function on the interval \([a,b]\). If \(f(a)<f(b)\) and if \(c\) is a number such that \(f(a)<c<f(b)\), then there is a point \(x \in (a,b)\) such that \[f(x)=c.\] A similar result holds if \(f(a)>f(b)\).

Proof. \([a,b]\) is connected so \(f\big[[a,b]\big]\) is connected in \(\mathbb{R}\) as well by the previous theorem. Thus if \(f(a)<c<f(b)\), then \(c \in f\big[[a,b]\big]\), so there is \(x \in [a,b]\) so that \(f(x)=c.\)$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark. The theorem stated above is sometimes called Darboux property or the intermediate value theorem.

Example

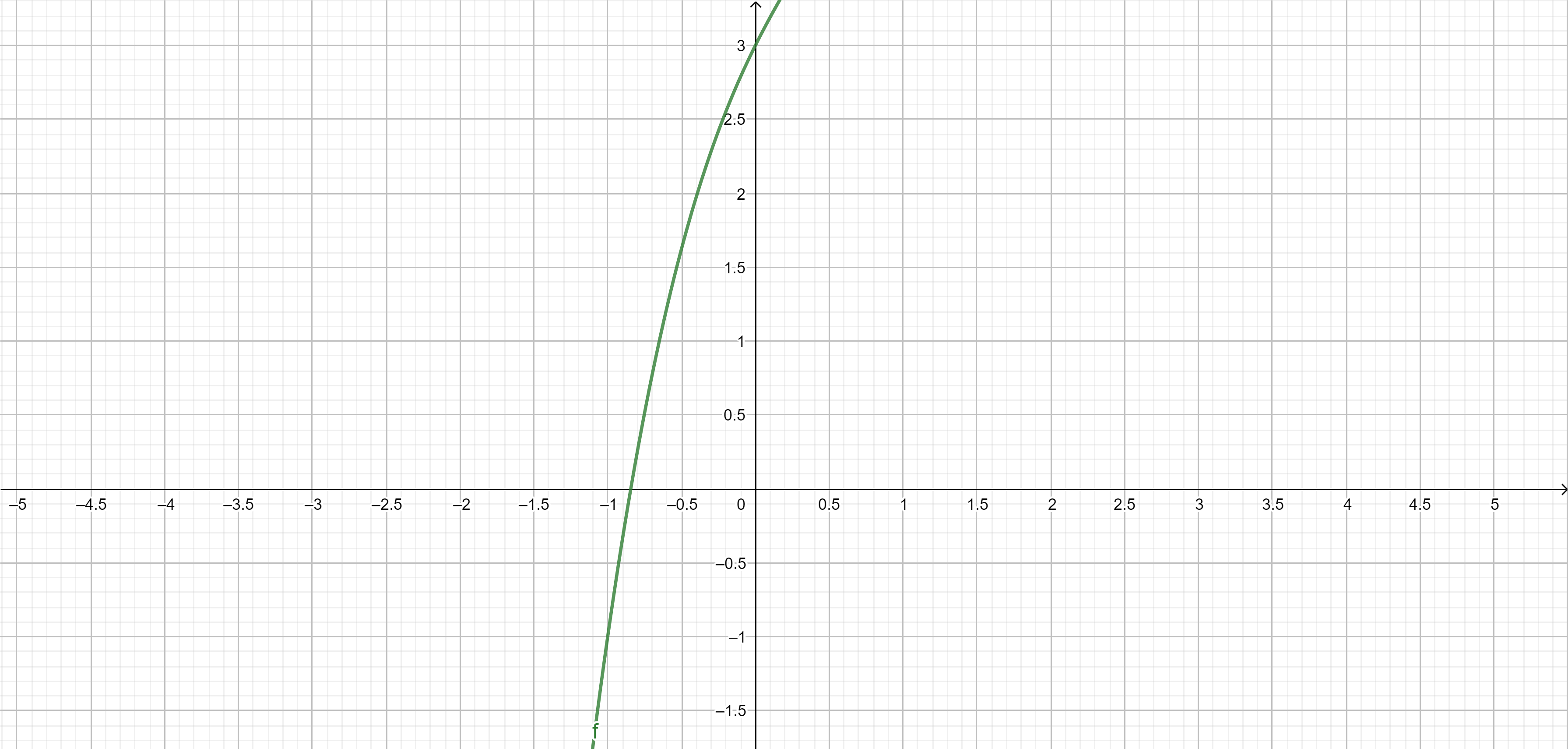

Exercise. Prove that the equation \[x^3-x^2+2x+3=0\] has a solution \(x_0\) such that \(-1 \leq x_0 \leq 0\).

Solution. Consider a continuous function \[f(x)=x^3-x^2+2x.\] We calculate \[f(-1)=-1, \quad \text{ and } \quad f(0)=3.\] It follows by the Darboux property that there is \(c \in [-1,0]\) such that \(f(c)=0\). Thus \(c\) is a solution of our equation as desired.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(f(x)=x^3-x^2+2x+3\), \(x_0 \approx -0.8437\)

Example

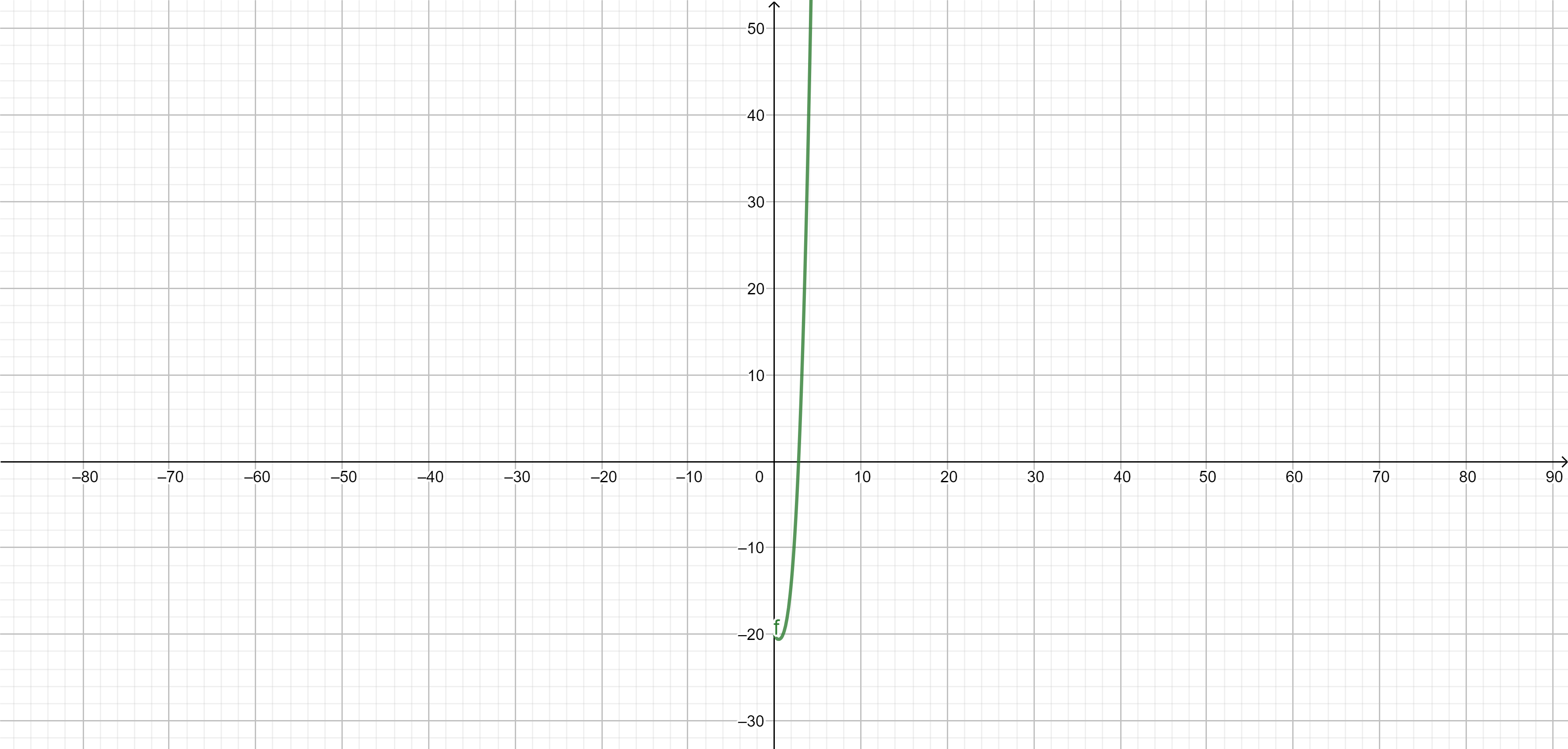

Exercise. Prove that the equation \[x^3=20+\sqrt{x}\] has solution \(x_0\).

Solution. Consider a continuous function \[f(x)=x^3-\sqrt{x}-20.\] We calculate \[f(1)=-20<0, \quad \text{ and } \quad f(4)=42>0.\]

It follows by the Darboux property that there is \(c \in [1,4]\) such that \(f(c)=0\). Thus \(c\) is a solution of our equation as desired.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(f(x)=x^3-\sqrt{x}-20\), \(x_0 \approx 2,7879\)

Uniform continuity

Uniformly continuous mappings

Uniformly continuous mappings. We say that \(f: X\to \mathbb R\) is uniformly continuous on \(X\subseteq \mathbb R\) if for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there exists \(\delta>0\) such that \[|f(x)-f(y)|<\varepsilon\] for all \(x,y \in X\) for which \[|x-y|<\delta.\]

Remark.

Uniform continuity is a property of a function on a set, whereas continuity can be defined at a single point.

Remarks

Remark 1.

If \(f\) is continuous on \(X\) then for each \(\varepsilon>0\) and \(p \in X\) there is \(\delta>0\) such that \(|x-p|<\delta\) implies \(|f(x)-f(p)|<\varepsilon\).

Thus \(\delta>0\) depends on \(p \in X\) and \(\varepsilon>0\).

Remark 2.

If \(f\) is uniformly continuous on \(X\) then for each \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(\delta>0\) such that for all \(x,y \in X\) if \(|x-y|<\delta\) then \(|f(x)-f(p)|<\varepsilon\).

Thus \(\delta>0\) depends only on \(\varepsilon>0\), but is uniform for all \(x,y \in X\).

Remark 3.

Uniform continuity implies continuity.

Continuity on compact spaces becomes uniform

Theorem. Let \(f:X\to \mathbb R\) be a continuous function defined on a compact set \(X\subseteq \mathbb R\). Then \(f\) is uniformly continuous on \(X\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given.

Since \(f\) is continuous we can associate to each point \(p \in X\) a positive number \(\delta_p>0\) such that if \(|p-q|<\delta_p\), then \(|f(p)-f(q)|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\).

Observe that \[X \subseteq \bigcup_{p \in X}\left(p-\frac{\delta_p}{2}, p+\frac{\delta_p}{2}\right).\]

Since \(X\) is compact there are \(p_1,p_2,\ldots,p_n \in X\) so that \[X \subseteq \bigcup_{k=1}^n\left(p_k-\frac{\delta_{p_k}}{2}, p_k+\frac{\delta_{p_k}}{2}\right).\]

Set \[\delta=\frac{1}{2}\min\left(\delta_{p_1},\ldots,\delta_{p_n}\right)>0.\]

Let \(p,q \in X\) be such that \(|p-q|<\delta\), then there is \(1 \leq m \leq n\) such that \(p \in \left(p_m-\frac{\delta_{p_m}}{2}, p_m+\frac{\delta_{p_m}}{2}\right).\) Hence \[|p_m-q| \leq |q-p|+|p_m-p| \leq \delta+\frac{\delta_{p_m}}{2}<\delta_{p_m}.\]

Thus we conclude \[|f(p)-f(q)| \leq |f(p)-f(p_m)|+|f(p_m)-f(q)|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon.\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example

Exercise. Let \(f(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\). Determine if it is uniformly continuous on \([1,2]\).

Solution. The interval \([1,2]\) is compact and the function \(f\) is continuous at every point of \([1,2]\). Hence, by the previous theorem, it is uniformly continuous.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Exercise. Let \[f(x)=\begin{cases}\frac{1}{x} \text{ if }x\neq 0,\\ 0 \text{ if }x=0. \end{cases}\] Determine if it is uniformly continuous on \([1,2]\).

Solution. The interval \([1,2]\) is compact and the function \(f\) is continuous at every point of \([1,2]\). Hence, by the previous theorem, it is uniformly continuous.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Exercise. Let \[f(x)=\begin{cases}\frac{1}{x} \text{ if }x\neq 0,\\ 0 \text{ if }x=0. \end{cases}\] Determine if it is uniformly continuous on \([0,1]\).

Solution. Let us consider \(a_n=\frac{1}{n}\). Then \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=0\), but \[\lim_{n \to \infty}f(a_n)=\lim_{n \to \infty}n \neq f(0)=0,\] so \(f\) is not continuous at the point \(0\), so it is not uniformly continuous.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Exercise. Show that the function \[f(x)=\begin{cases}\frac{1}{x} \text{ if }x\neq 0,\\ 0 \text{ if }x=0, \end{cases}\qquad \text{ is not uniformly continuous on $(0, 1)$.}\]

Solution. It can be checked that \(f\) is continuous on \((0,1)\).

Suppose that \(f\) is uniformly continuous, then for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(\delta>0\) such that for every \(x, y\in(0, 1)\) if \(|x-y|<\delta\) then \[|f(x)-f(y)|<\varepsilon.\]

We will use this condition with \(\varepsilon=1\) and \(x=\frac{1}{n}\) and \(y=\frac{1}{n+1}\).

This leads to a contradiction, since if \(\frac{1}{n}<\delta\), then we see that \[|x-y|=\frac{1}{n(n+1)}<\delta \quad \text{implies}\quad 1=|n-{n+1}|=|f(x)-f(y)|<1.\]

Discontinuities

Discontinuities

Discontinuities. If \(x\) is a point in the domain of a function \(f\) at which \(f\) is not continuous we say that

\(f\) is discontinuous on \(X\),

or \(f\) has a discontinuity at \(x\in X\).

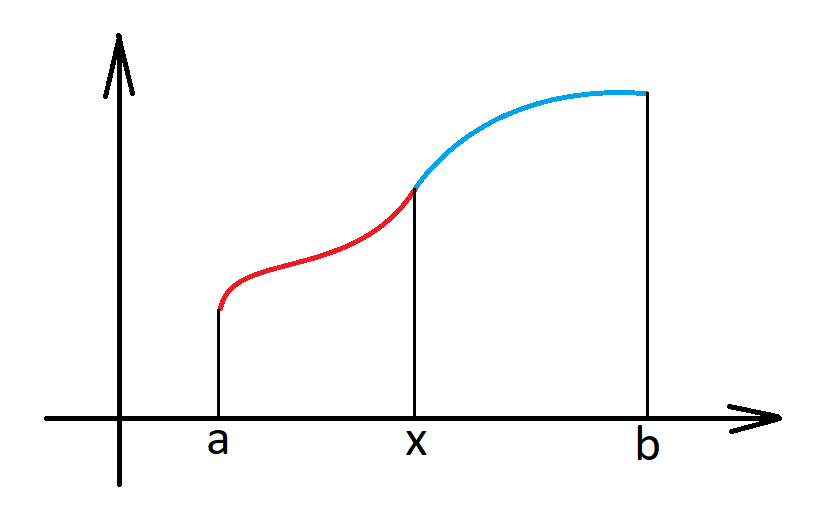

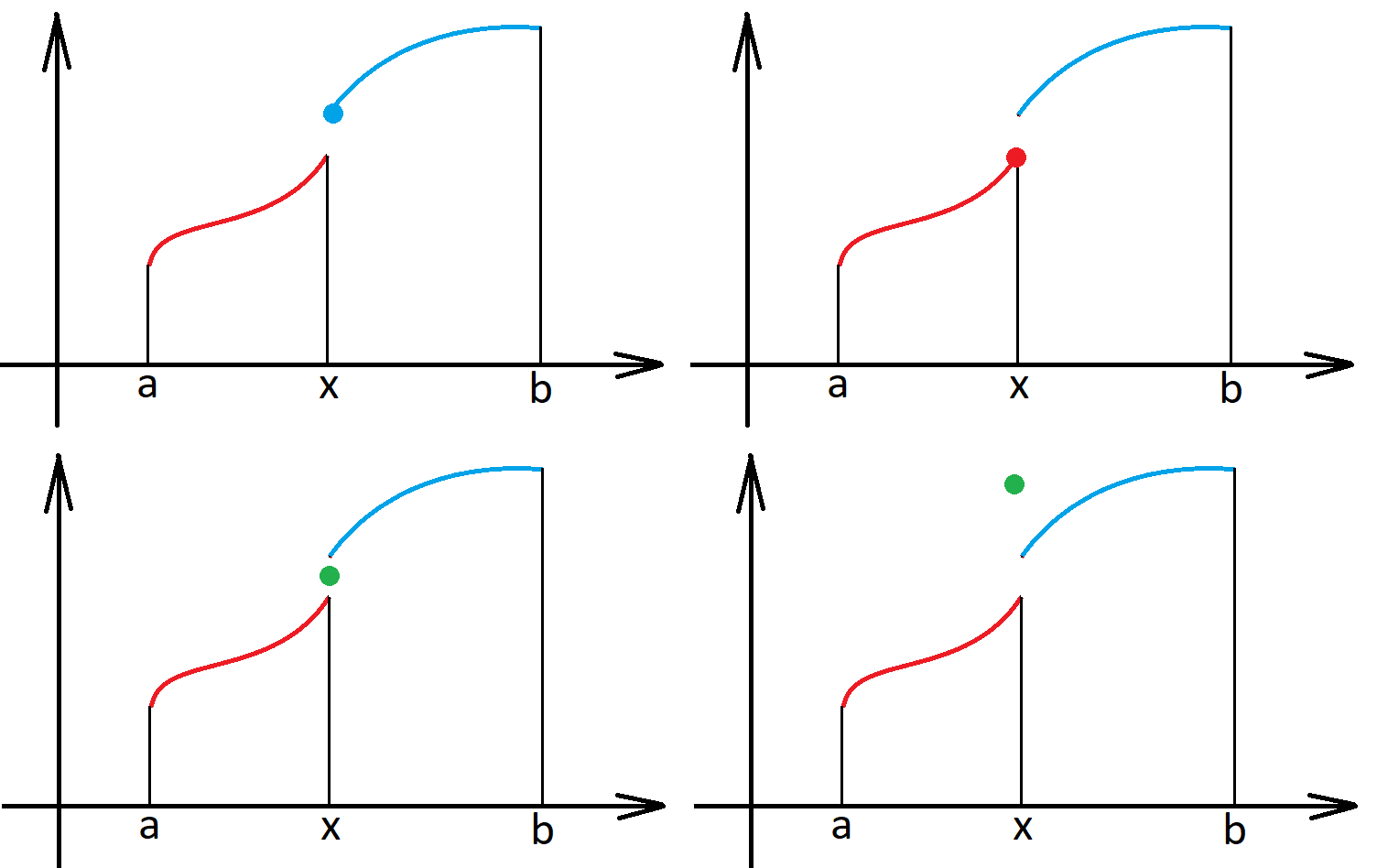

Definition. Let \(f:(a,b)\to \mathbb R\). Consider any \(x\) such that \(a< x <b\).

We write \(f(x+)=q\) if \(f(t_n) \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ q\) for all sequences \((t_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) in \({\color{blue}(x,b)}\) such that \(t_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ x\).

Similarly, \(f(x-)=q\) if \(f(t_n) \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ q\) for all sequences \((t_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) in \({\color{red}(a,x)}\) such that \(t_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ x\).

It is clear that for any \(x \in (a,b)\) \(\lim_{t \to x}f(t)\) exists iff \(f(x+)=f(x-)=\lim_{t \to x}f(t)\).

\(f(x+)\) and \(f(x-)\) - picture

Discontinuity of first and second kind

Let \(f:(a,b)\to \mathbb R\) be given.

Discontinuity of the first kind. If \(f\) is discontinuous at a point \(x\) and if \(f(x+)\) and \(f(x-)\) exist, then \(f\) is said to have discontinuity of the first kind or simple discontinuity at \(x\).

Discontinuity of the second kind. Otherwise the discontinuity is said to be of the second type.

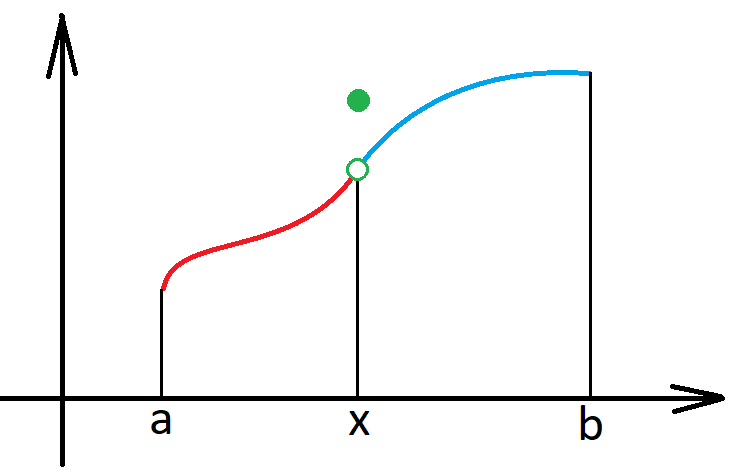

Remark. There are two ways in which a function can have a simple discontinuity:

either \(f(x+) \neq f(x-)\),

or \(f(x+)=f(x-)\neq f(x)\).

\(f(x+) \neq f(x-)\)

\(f(x+)=f(x-)\neq f(x)\)

Continuous from the left and from the right

Continuous from the left. If \(f(x-)=f(x)\) for all \(x \in (a,b)\) then we say that \(f\) is continuous from the left.

Continuous from the right. If \(f(x+)=f(x)\) for all \(x \in (a,b)\) then we say that \(f\) is continuous from the right.

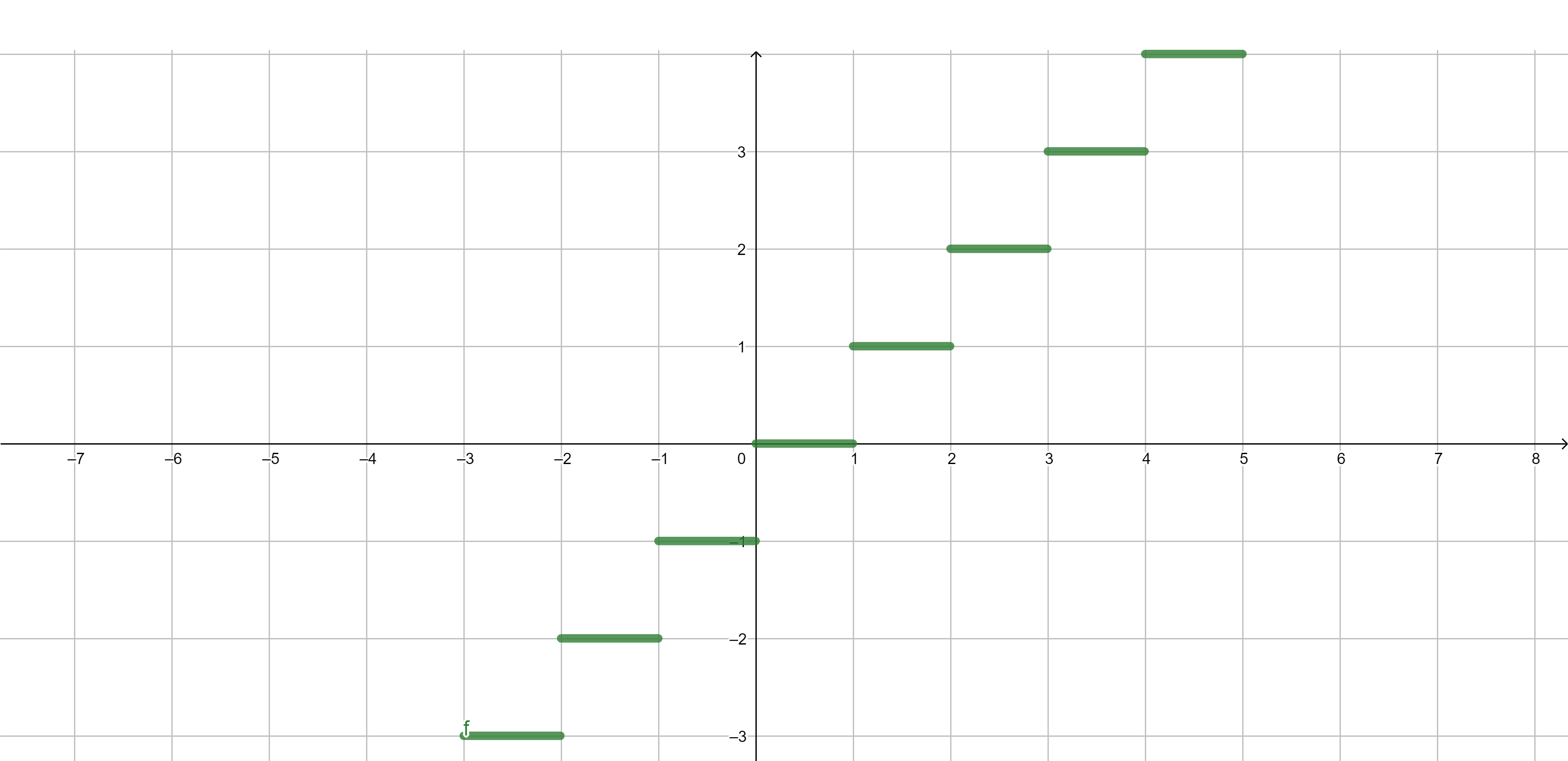

Integer part

Integer part \[\lfloor x\rfloor=\max\{n \in \mathbb{Z}:n \leq x\}\]

\[\text{\color{blue} is continuous from the right.}\].

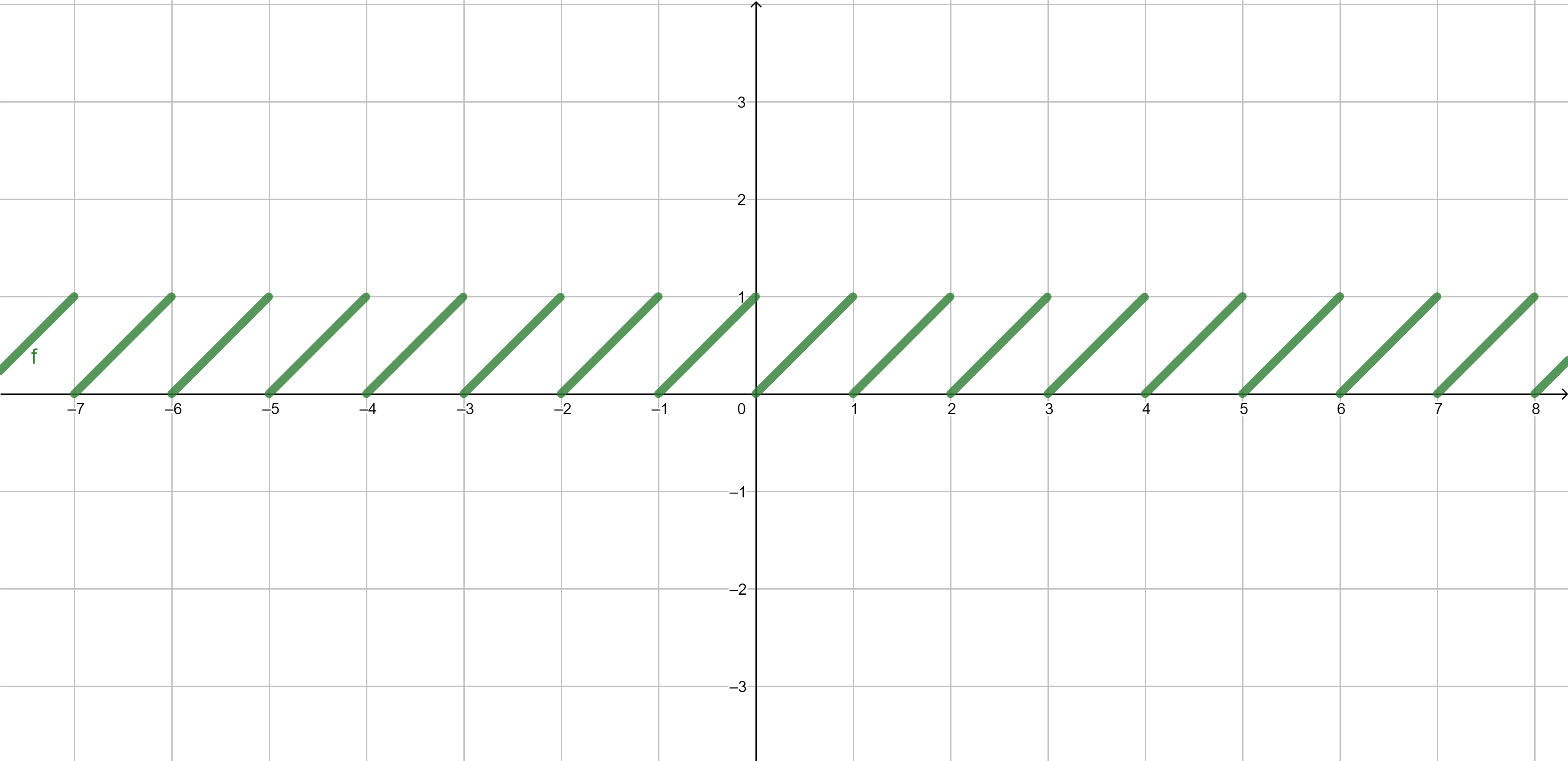

Fractional part

Fractional part \[\{x\}=x-\lfloor x\rfloor\]

\[\text{\color{blue} is also continuous from the right.}\].

Examples involving characteristic function of \(\mathbb{Q}\)

Characteristic function of \(\mathbb{Q}\). The function \[f(x)=\begin{cases} 1 \text{ if }x \in \mathbb{Q},\\ 0 \text{ if }x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \mathbb{Q}. \end{cases}\] has a discontinuity of the second kind at every point \(x\) since neither \(f(x+)\) nor \(f(x-)\) exists.

Characteristic function of \(\mathbb{Q}\) times linear functio. Define \[f(x)=\begin{cases} x \text{ if }x \in \mathbb{Q},\\ 0 \text{ if }x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \mathbb{Q}. \end{cases}\] Then \(f\) is continuous at \(x=0\), and \(f\) has a discontinuity of the second kind at every other point \(x\) since neither \(f(x+)\) nor \(f(x-)\) exists.

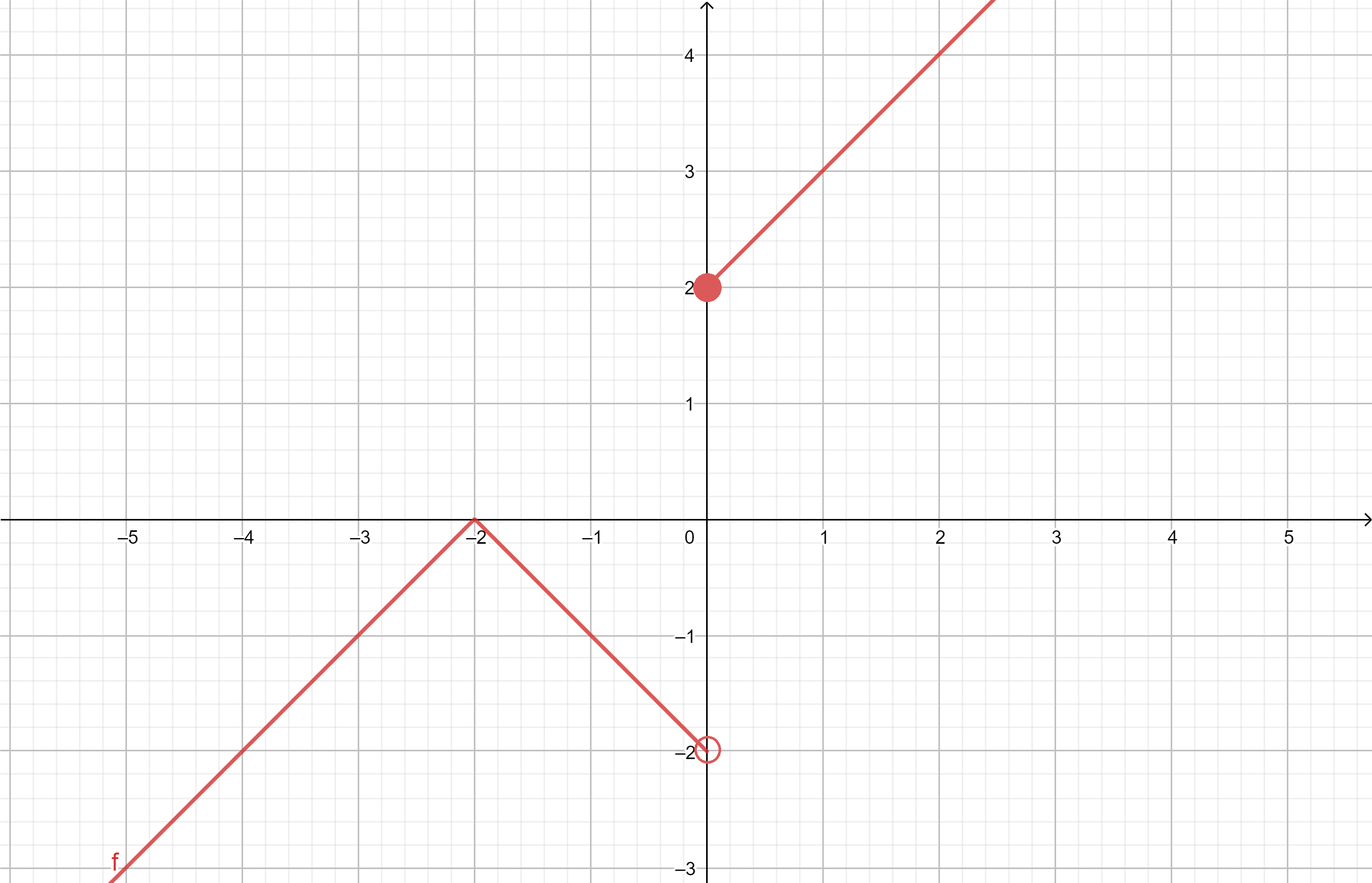

Example

An example of a function with a simple discontinuity at \(x=0\) that is continuous at every other point is given by the following formula \[f(x)=\begin{cases} x+2 &\text{ if }x <-2,\\ -x-2 &\text{ if }x \in [-2,0),\\ x+2 &\text{ if }x>0. \end{cases}\]

Monotonically increasing and decreasing functions

Monotonically increasing (and decreasing) function. Let \(f:(a,b) \to \mathbb{R}\), then \(f\) is said to be monotonically increasing on \((a,b)\) if \(a<x<y<b\) implies \(f(x) \leq f(y)\). If \(f(x) \geq f(y)\) we obtain the definition of a monotonically decreasing function.

Theorem. Let \(f\) be a monotonically increasing on \((a,b)\). Then \(f(x+)\) and \(f(x-)\) exist at every point at \(x\in (a,b)\). More precisely, \[\sup_{a <t<x}f(t)=f(x-) \leq f(x) \leq f(x+) \leq \inf_{x<t<b}f(t).\]

Furthermore, if \(a<x<y<b\) then \(f(x+) \leq f(y-)\). Analogous result remains true for monotonically decreasing functions.

The set \[E=\{f(t)\;:\; a <t<x\}\] is bounded by \(f(x)\) hence \(A=\sup E \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(A \leq f(x)\).

We have to show \(f(-x)=A\).

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Since \(A=\sup E\) there is \(\delta>0\) such that \(a<x-\delta<x\) and \(A-\varepsilon<f(x-\delta) \leq A\). Since \(f\) is monotonic \[f(x-\delta) \leq f(t) \leq A \quad \text{ for }\quad t \in (x-\delta,x).\]

Thus \(A-\varepsilon<f(t) \leq A\), so \[|f(x)-A|<\varepsilon \quad \text{ for }\quad t \in (x-\delta,x).\]

Thus \(A=f(x-)\). In a similar way we prove \(f(x+)=\inf_{x<t<b}f(t)\).

Next if \(a<x<y<b\), then

\[f(x+)=\inf_{x<t<b}f(t)=\inf_{x<t<y}f(t).\]

Similarly \[f(y-)=\sup_{a<t<y}f(t)=\sup_{x<t<y}f(t).\]

Thus \[f(x+)=\inf_{x<t<y}f(t) \leq \sup_{x<t<y}f(t) = f(y-).\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Corollary. Monotonic functions have no discontinuities of the second kind.

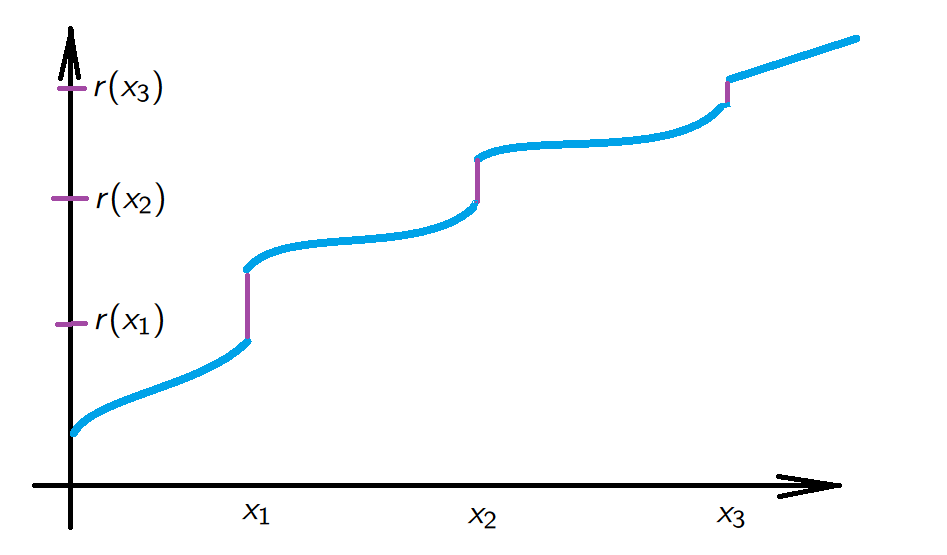

Theorem

Theorem. Let \(f:(a,b) \to \mathbb{R}\) be monotonic. Then the set of points of \((a,b)\) of which \(f\) is discontinuous is at most countable.

Proof. Wlog we may assume that \(f\) is increasing.

Let \(E\) be the set of points at which \(f\) is discontinuous.

With every point \(x \in E\) we associate a rational number \(r(x) \in \mathbb{Q}\) such that \[f(x-) <r(x)<f(x+),\] so \(r:E \to \mathbb{Q}\).

Since \(x_1<x_2\) implies \(f(x_1+) \leq f(x_2-)\) we see that \(r(x_1) \neq r(x_2)\) if \(x_1 \neq x_2\).

We have established that the function \(r:E \to \mathbb{Q}\) is injective, thus \[{\rm card\;}(E) \leq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{Q})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N}). \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]