5. Dirichlet box principle; Cartesian products, relations and functions PDF

Integer and fractional part, absolute value

Integer and fractional part, absolute value 1/2

Let \(x\in \mathbb{R}\).

Integer part. The integer part of \(x\) is \[\lfloor x\rfloor=\max\{n \in \mathbb{Z}\;:\; n \leq x\}.\]

Fractional part. The fractional part of \(x\) is \[\{x\}=x-\lfloor x \rfloor.\]

Integer and fractional part, absolute value 2/2

Absolute value. The absolute value of \(x\) is \[\begin{aligned} |x|=\begin{cases} \hspace{0.295cm} x &\text{ if }x \geq 0, \\ -x &\text{ if }x<0. \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

Example 1. If \(x=2.5\), then \(\lfloor x \rfloor=2\), \(\{x\}=0.5\), \(|x|=2.5\).

Example 2. If \(x=-3.3\), then \(\lfloor x\rfloor=-4\), \(\{x\}=0.7\), \(|x|=3.3\).

Propoerties of \(|x|\)

Theorem. For \(x, y\in \mathbb R\) one has

\(|x|=\sqrt{x^2}\),

\(|xy|=|x||y|\),

\(x\le |x|\) and \(x\ge -|x|\)

\(|x+y| \leq |x|+|y|\), (triangle inequality).

\(||x|-|y|| \leq |x-y| \leq |x|+|y|\), (triangle inequality).

Proof:.

Note that \(|x|^2=x^2\) and the equation \(z^2=x^2\) has a unique solution for \(z>0\). Since both \(z=|x|\) and \(z=\sqrt{x^2}\) solve this equation we must have \[|x|=\sqrt{x^2}.\]

Observe that \(|xy|=\sqrt{(xy)^2}=\sqrt{x^2y^2}=\sqrt{x^2}\sqrt{y^2}=|x||y|\).

Clearly \(x\le |x|\) for all \(x\in \mathbb R\). Similarly, \(-x\le |x|\) giving \(x\ge-|x|\).

Since \(x\le |x|\) and \(y\le |y|\), then \(x+y\le |x|+|y|\). We also have \(-(|x|+|y|)\le x+y\), since \(-|x|\le x\) and \(-|y|\le y\). Hence \[-( |x|+|y|)\le x+y\le |x|+|y| \qquad \Longleftrightarrow\qquad |x+y| \leq |x|+|y|\]

Note that \[\begin{aligned} &{\color{red}|x|=|y+x-y|\le |y|+|x-y|,} \quad \text{ and }\\ &{\color{blue}|y|=|x+y-x|\le |x|+|x-y|.} \end{aligned}\] Thus \[\begin{aligned} {\color{blue}-|x-y|\le |x|-|y|} \quad \text{ and } \quad {\color{red}|x|-|y|\le |x-y|}, \end{aligned}\] which gives \[\hspace{4cm}||x|-|y|| \leq |x-y|. \hspace{3cm}\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Exercise

Two \(a,b \in \mathbb{R}\) are equal iff for every \(\varepsilon>0\) it follows \[|a-b|<\varepsilon.\]

Proof (\(\Leftarrow\)). If \(a=b\), then \(|a-b|=0<\varepsilon\) for any \(\varepsilon>0\).

Proof (\(\Rightarrow\)). Suppose that for any \(\varepsilon>0\) one has \(|a-b|<\varepsilon\). If \(a=b\), then we are done. Assume that \(a \neq b\) and take \(\varepsilon_0=|a-b|>0.\)

Taking any \(0<\varepsilon<\varepsilon_0\) one has \[0<\varepsilon_0=|a-b|<\varepsilon<\varepsilon_0,\] which is impossible.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Dirichlet principle

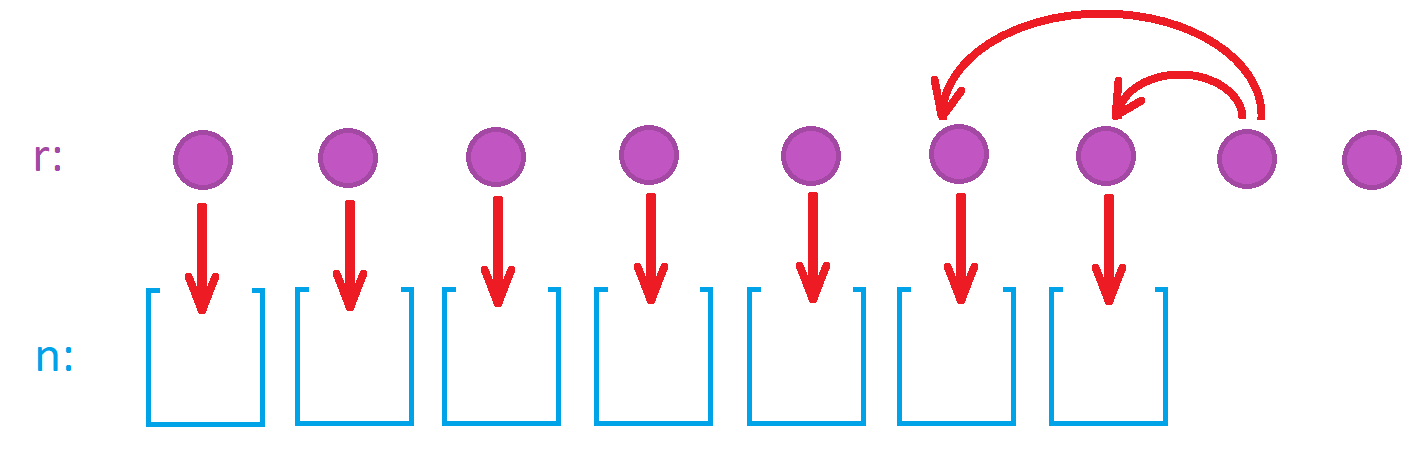

Pigeonhole principle

Dirichlet’s box principle. If \(r\) objects are placed in \(n\) boxes and \(r>n\), then at least one of the boxes contains more than one object.

Dirichlet principle

Theorem (Dirichlet). Let \(\alpha,Q\) be real numbers, \(Q \geq 1\). There exist \(a,q \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(1 \leq q \leq Q\) and \(a,q\) are relatively prime such that \[\left|\alpha-\frac{a}{q}\right| < \frac{1}{qQ} \leq \frac{1}{q^2}.\]

Proof. Let \(N = \lfloor Q \rfloor\). We will consider three cases.

Case 1. \(\{\alpha q\} \in \big[0,\frac{1}{N+1}\big)\),

Case 2. \(\{\alpha q\} \in \big[\frac{N}{N+1},1\big)\),

Case 3. \(\{\alpha q\} \not\in \big[0,\frac{1}{N+1}\big)\cup \big[\frac{N}{N+1},1\big)\).

Suppose that \[\{\alpha q\} \in \left[0,\frac{1}{N+1}\right)\] for some positive integer \(q \leq N\).

If \(a=\lfloor \alpha q\rfloor\), then \[0 \leq \{\alpha q\}=\alpha q-a < \frac{1}{N+1},\] so (dividing both sides by \(q\)): \[\left|\alpha -\frac{a}{q}\right| < \frac{1}{(N+1)q}<\frac{1}{qQ}<\frac{1}{q^2}.\]

Suppose that \[\{\alpha q\} \in \left[\frac{N}{N+1},1\right)\] for some positive integer \(q \leq N\).

If \(a=\lfloor \alpha q\rfloor+1\), then \[\frac{N}{N+1} \leq \{\alpha q\}=\alpha q-Q+1 \leq 1,\] implies \[|\alpha q-a| <\frac{1}{N+1},\]

so (dividing both sides by \(q\)): \[\left|\alpha -\frac{a}{q}\right| < \frac{1}{(N+1)q}<\frac{1}{qQ}<\frac{1}{q^2}.\]

Suppose that \[\{\alpha q\} \in \left[\frac{1}{N+1},\frac{N}{N+1}\right).\] for all \(1 \leq q \leq N\). Then each of the \({\color{red}N}\) numbers \[\{\alpha\},\{2\alpha\},\{3\alpha\},\ldots,\{N\alpha\}\] lies in \({\color{red}N-1}\) intervals \[\left[\frac{1}{N+1},\frac{2}{N+1}\right),\left[\frac{2}{N+1},\frac{3}{N+1}\right),\left[\frac{3}{N+1},\frac{4}{N+1}\right),\ldots,\left[\frac{N-1}{N+1},\frac{N}{N+1}\right).\]

Therefore, by the Dirichlet’s box principle there exist \(1 \leq j \leq N-1\) and \(q_1,q_2 \in \{1,2,\ldots,N\}\), \(q_1<q_2\), such that \[q_1,q_2 \in \left[\frac{j}{N+1},\frac{j+1}{N+1}\right).\]

Let \(q=q_2-q_1\) and \[a=\lfloor \alpha q_2\rfloor-\lfloor \alpha q_1\rfloor.\]

Then \[\begin{aligned} |\alpha q-a|&=|(\alpha q_2-\lfloor \alpha q_2\rfloor)-(\alpha q_1-\lfloor \alpha q_1\rfloor)|\\&=|\{\alpha q_2\}-\{\alpha q_1\}|<\frac{1}{N+1}. \end{aligned}\]

Thus \[\left|\alpha -\frac{a}{q}\right| < \frac{1}{(N+1)q}<\frac{1}{qQ}<\frac{1}{q^2}.\] The proof is finished. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cartesian products, relations and functions

Ordered pairs

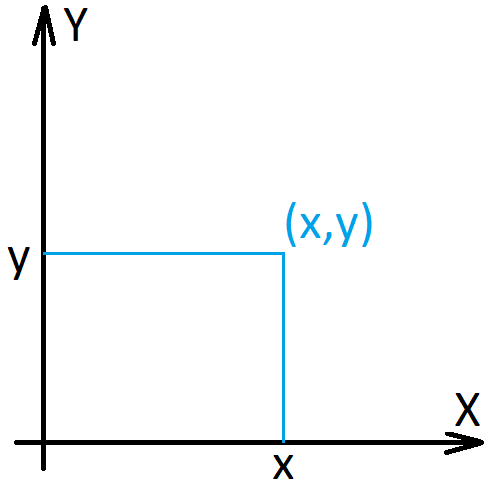

Ordered pairs. The ordered pair \((x, y)\) is precisely the set \(\{\{x\}, \{x, y\}\}\).

Theorem. \((x, y)=(u, v)\) iff \(x=u\) and \(y=v\).

Cartesian products

Cartesian products. If \(X\) and \(Y\) are sets, their Cartesian product \(X \times Y\) is the set of all ordered pairs \((x,y)\) such that \(x \in X\) and \(y \in Y\).

\[X \times Y=\{(x,y)\;:\;x \in X,y \in Y \}\]

Cartesian products - examples

Example 1. If \(X=\{1,2,3\}, Y=\{4,5\}\), then \[X \times Y=\{(1,4),(2,4),(3,4),(1,5),(2,5),(3,5)\}.\]

Example 2. If \(X=\{1,2\}, Y=\{1,2\},\) then \[X \times Y=\{(1,1),(1,2),(2,1),(2,2)\}.\]

Example 3. If \(X \neq \varnothing\) and \(Y=\varnothing\), then \(X \times Y=\varnothing\).

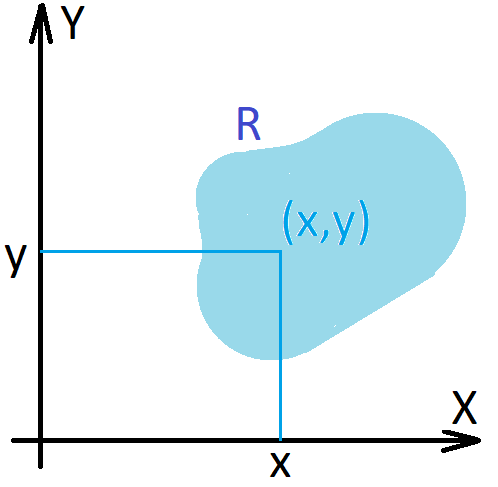

Relations

Relations. A relation from \(X\) to \(Y\) is a subset \(R\) of \(X \times Y\), i.e. \(R\subseteq X \times Y\).

If \(X=Y\) we speak about relations on \(X\).

If \(R\) is a relation from \(X\) to \(Y\) we shall sometimes write \(xRy\) to mean that \((x,y) \in R \subseteq X \times Y\).

Relations - examples

Example 1. \[xRy \iff x=y\]

This relation corresponds to the diagonal \(\Delta\) in \(X \times X\): \[\Delta=\{(x,x)\;:\;x \in X\} \subseteq X \times X.\]

Now we present more examples of relations.

Equivalence relations

Equivalence relations. An equivalence relation is a relation on \(X\) such that:

\(xRx\) for all \(x \in X\), (reflexivity).

\(xRy\) iff \(yRx\) for all \(x,y \in X\), (symmetry).

if \(xRy\) and \(yRz\), then \(xRz\) for all \(x,y,z \in R\). (transitivity).

Equivalence classes. An equivalence class of an element \(x\in X\) is the set \(\{y \in X:xRy\}\).

\(X\). is the disjoint union of the equivalence classes.

Equivalence relations - examples 1/2

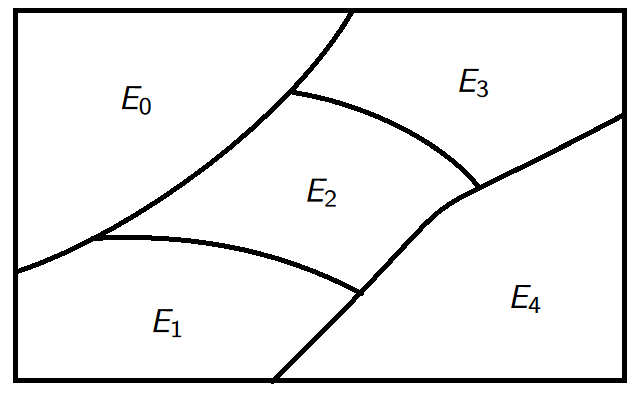

Example. Let \(X=\mathbb{Z}\). Consider \[xRy \iff x \equiv y \mod 5 \iff 5|(x-y).\]

the equivalence classes corresponding to the relation \(R\) are the sets: \[E_0=\{5k\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\},\] \[E_1=\{5k+1\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\},\] \[E_2=\{5k+2\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\},\] \[E_3=\{5k+3\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\},\] \[E_4=\{5k+4\;:\; k \in \mathbb{Z}\}.\]

Equivalence relations - examples 2/2

We have \[\mathbb{Z}=E_0 \cup E_1 \cup E_2 \cup E_3 \cup E_4.\]

Example 2. Orderings are also relations (will be discussed later).

Functions

Functions. A function \(f:X \to Y\) is a relation from \(X\) to \(Y\) with the property that for every \(x \in X\) there is a unique element \(y \in Y\) such that \(xRy\) in which case we write \[y=f(x).\]

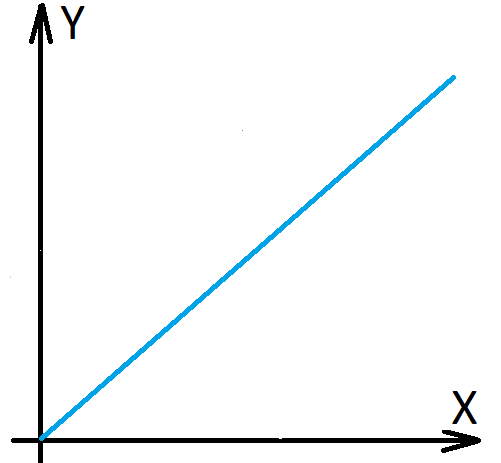

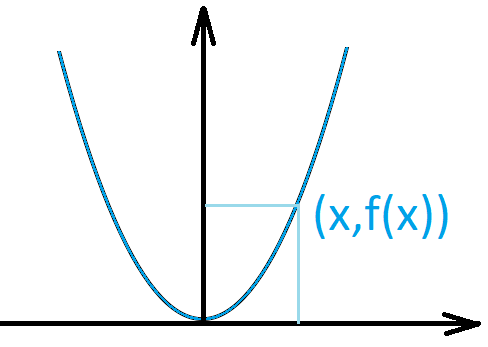

Example 1. \(X=\mathbb{R}\), \(f(x)=x^2\).

A relation which is not a function

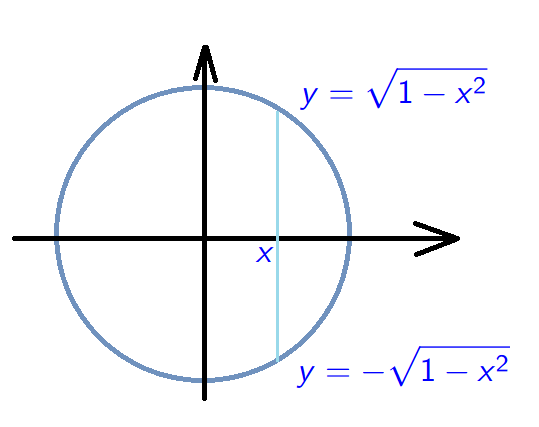

Example 2. \[D=\{(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2\;:\;x^2+y^2=1\}.\] This is not a function!

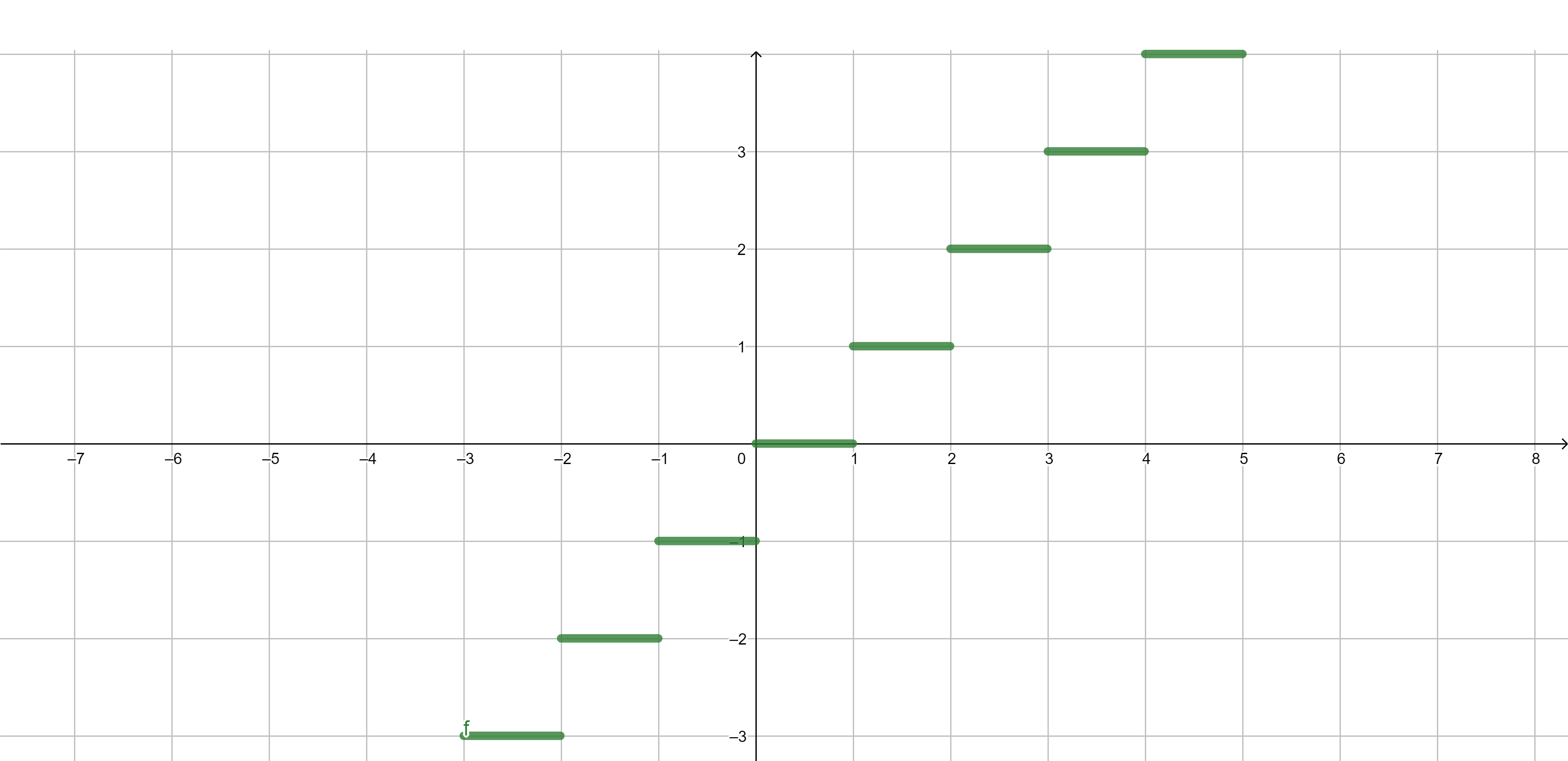

Examples of functions - integer part

Integer part \[\lfloor x\rfloor=\max\{n \in \mathbb{Z}:n \leq x\}.\]

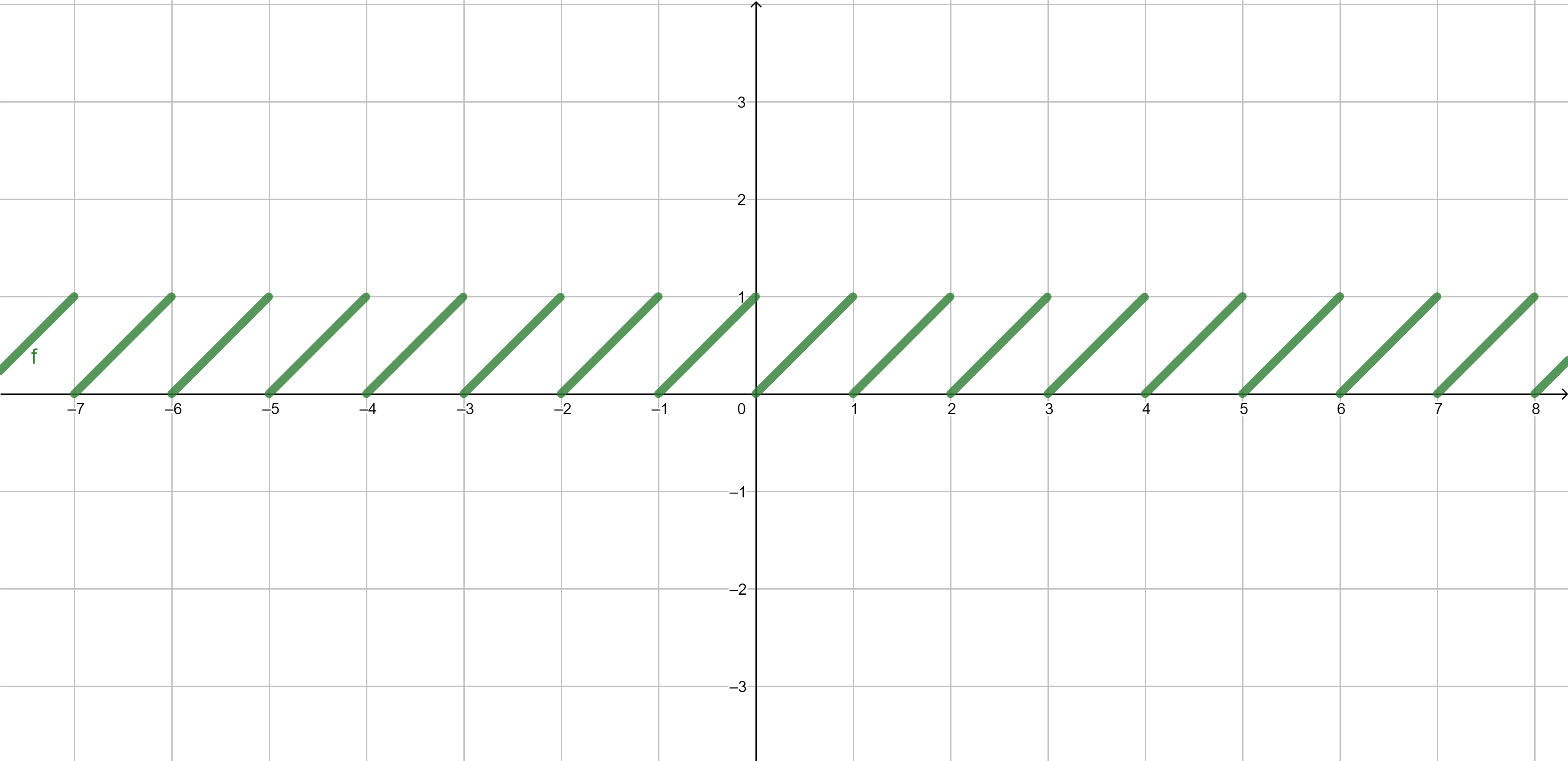

Examples of functions - fractional part

Fractional part \[\{x\}=x-\lfloor x\rfloor.\]

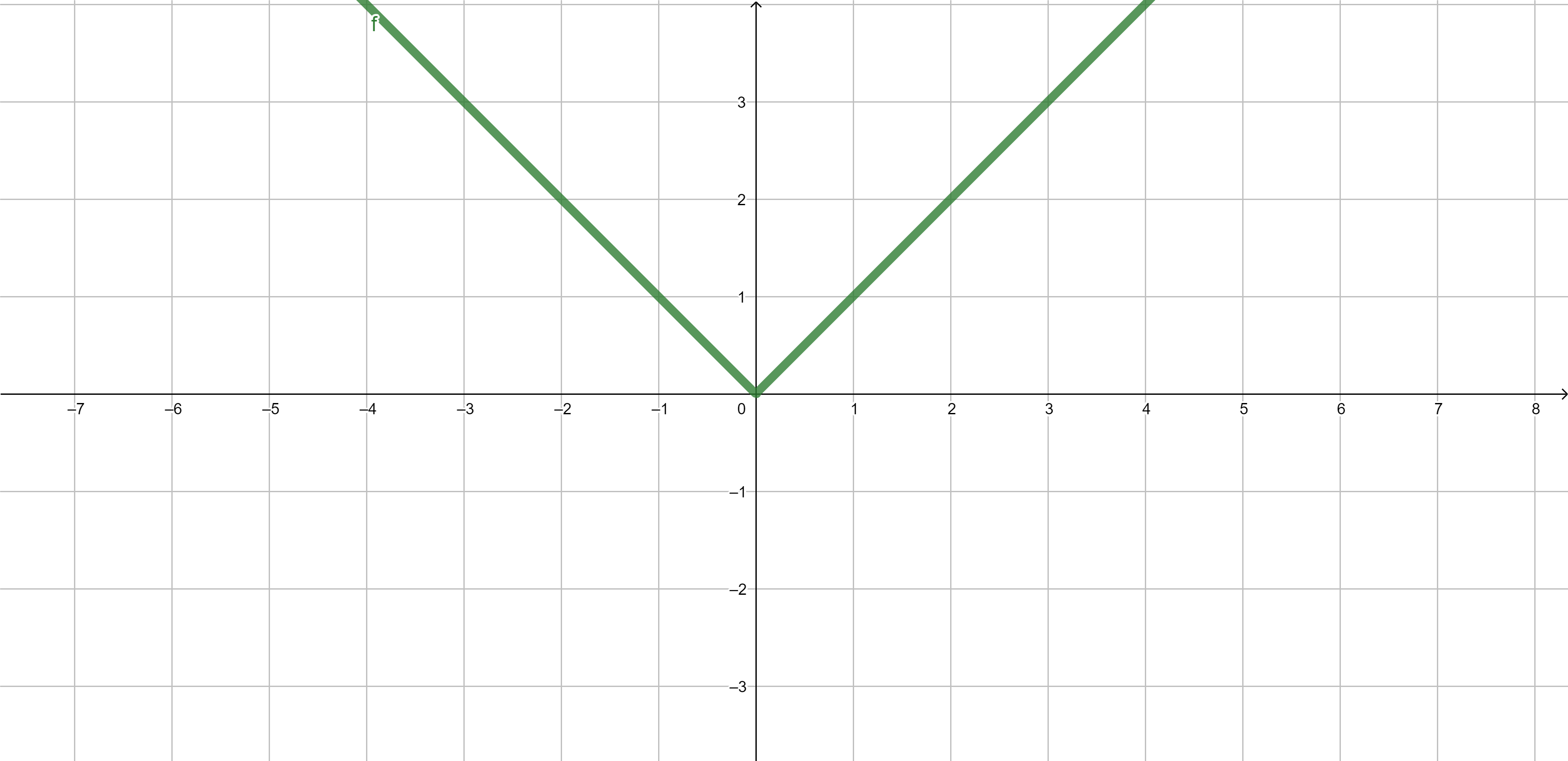

Examples of functions - absolute value

Absolute value \[|x|=\begin{cases} x & \text{ if }x\geq 0,\\ -x & \text{ if }x<0. \end{cases}.\]