10. The Limit of a Sequence; The Algebraic and Order Limit; Theorems PDF

Sequences

Exercise

Exercise. Two \(a,b, \in \mathbb{R}\) are equal iff for every \(\varepsilon>0\) it follows \[|a-b|<\varepsilon.\]

Proof (\(\Leftarrow\)). If \(a=b\), then \(|a-b|=0<\varepsilon\) for any \(\varepsilon>0\).

Proof (\(\Rightarrow\)). Suppose that for any \(\varepsilon>0\) we have \(|a-b|<\varepsilon\). If \(a=b\), then we are done. Assume that \(a \neq b\) and take \(\varepsilon_0=|a-b|>0.\)

Taking any \(0<\varepsilon<\varepsilon_0\) one have \[0<\varepsilon_0=|a-b|<\varepsilon<\varepsilon_0,\] which is impossible.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Sequences

Definition. A sequence is a function whose domain is \(\mathbb{N}\).

Example. Common ways to describe sequences:

\(\left(1,\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{5},\ldots\right)\),

\(\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)_{n=1}^{\infty}=\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}=\left(\frac{2}{1},\frac{3}{2},\frac{4}{3},\ldots\right)\),

\((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\), where \(x_n=2^n\) for each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\),

\((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\), where \(a_1=2\) and \(a_{n+1}=\frac{a_n}{2}\).

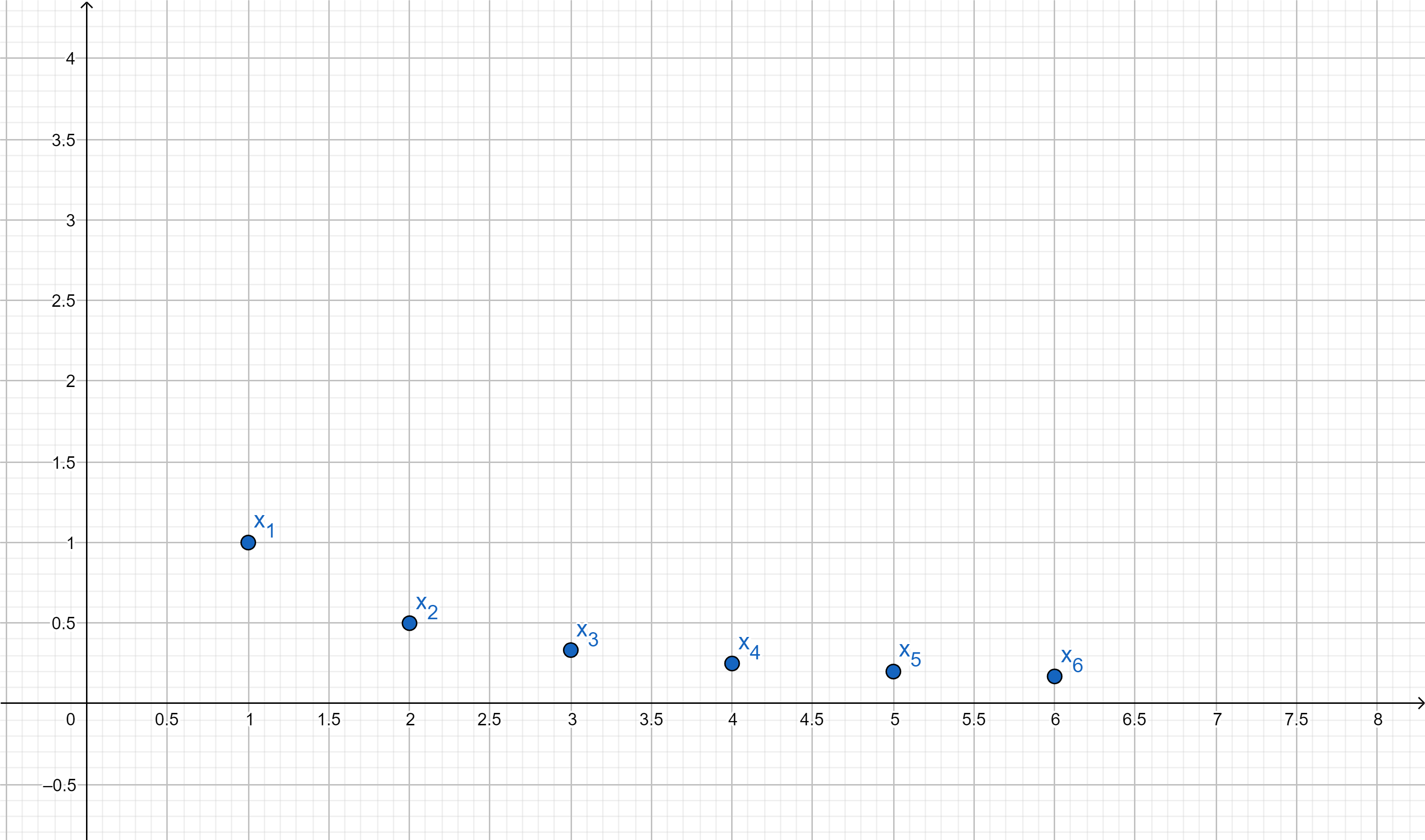

Graph of a sequence

Consider \(x_n=\frac{1}{n}\), then

Asymptotic behaviour of a sequence

Question. Is there a reasonable way how to measure how small the sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) of real numbers is asymptotically (\(\equiv\) at infinity)?

We take an arbitrary \(\varepsilon>0\) and since \(x_n=\frac{1}{n}\) then by the Archimedian property we always find \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \(\frac{1}{N_{\varepsilon}}<\varepsilon.\)

Moreover, since \(x_{n+1}=\frac{1}{n+1}<\frac{1}{n}=x_n\) for every \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) thus

\[\frac{1}{n}<\varepsilon \quad \text{ for any }\quad n \geq N_{\varepsilon}. \hspace{2cm} {\color{purple}(*)}\]

Since \(\varepsilon>0\) is arbitrary and (*) holds for all \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) (we will usually say that (*) holds for all but finitely many integers or for all sufficiently large integers).

One can also think that the sequence \((x_{n})_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is asymptotically small or small at infinity.

Convergence of a sequence

Convergence of a sequence

Convergence of a sequence. A sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges to a real number \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) if, for all \(\varepsilon>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that whenever \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) it follows that \[|x-x_n|<\varepsilon.\]

To indicate that \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges to \(a\in \mathbb R\) we will write either

\[\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a\quad \text{ or }\quad \lim a_n=a\quad \text{ or } \quad a_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ a\quad \text{ or } \quad a_n \to a.\].

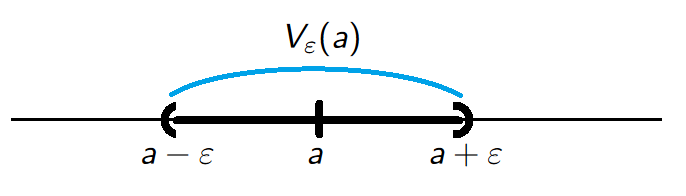

\(\varepsilon\)-neighbourhood

\(\varepsilon\) -neighbourhood. Given \(a \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(\varepsilon>0\) the set \[V_{\varepsilon}(a)=\{x \in \mathbb{R}\;:\; |x-a|<\varepsilon\}\] is called the \(\varepsilon\)-neighbourhood or an open ball centered at \(a\) and radius \(\varepsilon\).

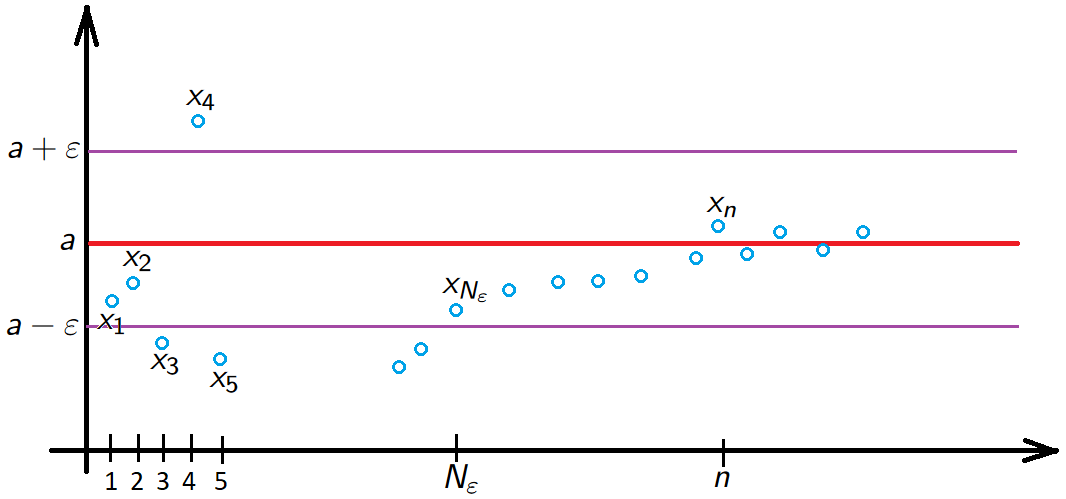

Convergence - illustration

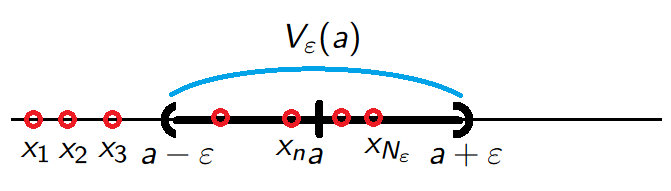

Convergence - topological version

Convergence - topological version. A sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges to \(a \in \mathbb{R}\) if, given any \(\varepsilon\)-neighbourhood \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\) of \(a\) contains all but finitely many terms of \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\).

Convergence of a sequence - exercise 1/2

Exercise. Prove \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}=0\).

Solution.

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary, but fixed.

Determine the choice of \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\). In our case we take

\[N_{\varepsilon}=\Big\lfloor\frac{1}{\varepsilon^2} \Big\rfloor+1.\]

Now show that \(N_{\varepsilon}\) actually works. Assume that \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\), then \[\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} \leq \frac{1}{\sqrt{N_{\varepsilon}}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\left\lfloor\frac{1}{\varepsilon^2} \right\rfloor+1}}<\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 / \varepsilon^2}}=\varepsilon.\]

Convergence of a sequence - exercise 2/2

With this \(N_{\varepsilon}\), we have \(|x_n-x|<\varepsilon\) for all \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\). Indeed, \[\left|\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}-0\right|=\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}<\varepsilon.\] Hence \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}=0.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Convergence of a sequence - exercise 1/2

Exercise. Prove \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{3n+2}{2n+1}=\frac{3}{2}\).

Solution.

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary, but fixed.

Determine the choice of \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\). In our case we take

\[N_{\varepsilon}=\Big\lfloor\frac{2}{\varepsilon} \Big\rfloor+1.\].

Now show that \(N_{\varepsilon}\) actually works. Assume that \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\), then \[\left|\frac{3n+2}{2n+1}-\frac{3}{2}\right| \leq \left|\frac{3n+2}{2n+1}-\frac{3n}{2n+1}\right|+\left|\frac{3n}{2n+1}-\frac{3n}{2n}\right|\]

Convergence of a sequence - exercise 2/2

Furthermore, for \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) we have \[\left|\frac{3n+2}{2n+1}-\frac{3n}{2n+1}\right| = \frac{2}{2n+1} \leq \frac{1}{n} < \frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\] \[\left|\frac{3n}{2n+1}-\frac{3n}{2n}\right|=\frac{3n(2n+1-2n)}{2n(2n+1)}<\frac{3}{4n}<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\]

Hence \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{3n+2}{2n+1}=\frac{3}{2}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Convergence of a sequence - exercise 1/2

Exercise. Prove \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{n}{n^3+3}=0\).

Solution.

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary, but fixed.

Determine the choice of \(N_{\varepsilon \in \mathbb{N}}\). In our case we take

\[N_{\varepsilon}=\Big\lfloor\frac{1}{\sqrt{\varepsilon}} \Big\rfloor+1.\].

Now show that \(N_{\varepsilon}\) actually works. Assume that \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\), then \[\frac{n}{n^3+3}\leq \frac{n}{n^3}=\frac{1}{n^2}< \varepsilon.\]

Convergence of a sequence - exercise 2/2

Thus for \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) we have \[\left|\frac{n}{n^3+3}-0\right|=\frac{1}{n^2}<\varepsilon.\] Hence \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{n}{n^3+3}=0.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Uniqueness of the limit

Uniqueness of the limit. The limit of the sequence, when it exists, must be unique.

Proof. Suppose that \[\lim_{n \to \infty}x_n=x \quad \text{ and } \quad \lim_{n \to \infty}x_n=y.\]

We have to prove that \(x=y\). Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary, then it suffices to show \(|x-y|<\varepsilon\). Note that

(*). \(\lim_{n \to \infty}x_n=x \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_1>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_1}^1 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_1}^1\quad \text{ implies } \quad |x_n-x|<\varepsilon_1.\]

(*). \(\lim_{n \to \infty}x_n=y \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_2>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_2}^2 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}^2\quad \text{ implies } \quad|x_n-y|<\varepsilon_2.\]

Applying (*) and (*) with \(\varepsilon_1=\varepsilon_2=\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\) we know that there are \(N_{\varepsilon_1}^1,N_{\varepsilon_2}^2 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[\begin{aligned} n \geq N_{\varepsilon_1}^1\quad \text{ implies } \quad |x_n-x|<\varepsilon_1,\\ n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}^2\quad \text{ implies } \quad|x_n-y|<\varepsilon_2. \end{aligned}\] Setting \(N_{\varepsilon}=\max(N_{\varepsilon / 2}^1, N_{\varepsilon / 2}^2)\), taking \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) and using the triangle inequality \[|x-y|=|(x-x_n)+(x_n-y)| \leq |x_n-x|+|x_n-y|< \frac{\varepsilon}{2}+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon.\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Bounded sequence

Bounded sequence. A sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is bounded if there exists \(M>0\) such that \[|x_n| \leq M\] for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Geometrically, this means that the interval \([-M,M]\) contains all terms of the sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\).

Example.

\(\left(5+\frac{1}{n}\right)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is bounded by \(6\),

\((n^2)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is not bounded.

Every convergent sequence is bounded

Theorem. Every convergent sequence is bounded.

Proof. Assume that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}x_n=x\). This is equivalent to the fact that for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\quad \text{ implies } \quad|x_n-x|<\varepsilon. \hspace{2cm} {\color{purple}(*)}\]

Applying (*) with \(\varepsilon=1\) we obtain \[|x_n-x|<1 \quad \text{ for any } \quad n \geq N_1.\] Thus \(|x_n|<1+|x|\) for any \(n \geq N_1\). Consider \[{\color{red}M=\max\{|x_1|,|x_2|,\ldots,|x_{N_1-1}|,|x|+1\}}\] we see that \(|x_n| \leq M\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and we are done. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Algebraic limits theorem

Theorem. Let \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a\) and \(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=b\). Then

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}(ca_n)=ac\),

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}(a_n+b_n)=a+b\),

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_nb_n=ab\),

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{a_n}{b_n}=\frac{a}{b}\) provided that \(b _n,b \neq 0\) for all \(n\in\mathbb N\).

Proof of (i). If \(c=0\) then there is nothing to do since \(ca_n=0\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), thus \(\lim_{n \to \infty}ca_n=0=ca\).

Assume that \(c \neq 0\). Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary but fixed and note that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_0>0\) there is \(N_{\varepsilon_0} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_0}\quad \text{ implies } \quad |a-a_n|<\varepsilon_0. \hspace{2cm} {\color{purple}(*)}\]

Applying (*) with \(\frac{\varepsilon}{c}\) in place of \(\varepsilon_0\) one gets that \[|ca_n-ca|=|c||a_n-a|<|c|\frac{\varepsilon}{|c|}=\varepsilon.\]

Thus we have shown that for any \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(\widetilde{N}_{\varepsilon}=N_{\varepsilon / |c|} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that if \(n \geq \widetilde{N}_{\varepsilon}\), then \[|ca_n-ca|<\varepsilon.\]

Hence \(\lim_{n \to \infty}ca_n=ca\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_1>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_1}^1 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that

\[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_1}^1\quad \text{ implies } \quad |a_n-a|<\varepsilon_1. \hspace{2cm} {\color{red}(*)}\]

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=b \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_2>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_2}^2 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}^2\quad \text{ implies } \quad|b_n-b|<\varepsilon_2.\hspace{2cm}{\color{blue}(*)}\]

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary but fixed. Applying (*) and (*) with \(\varepsilon_1=\varepsilon_2=\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\) one obtains \[\begin{aligned} n \geq N_{\varepsilon_1}^1\quad \text{ implies } \quad |a_n-a|<\varepsilon/2,\\ n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}^2\quad \text{ implies } \quad|b_n-b|<\varepsilon/2. \end{aligned}\]

By the triangle inequality for any \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}=\max(N_{\varepsilon_1}^1, N_{\varepsilon_2}^2)\) we see \[\begin{aligned} |a_n+b_n-(a+b)|&=|(a_n-a)+(b_n-b)| \\ &\leq |a_n-a|+|b_n-b|\\ &<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon. \end{aligned}\]

Since \(\varepsilon>0\) was arbitrary we proved that \[\lim_{n \to \infty}(a_n+b_n)=a+b.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_1>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_1}^1 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that

\[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_1}^1\quad \text{ implies } \quad |a_n-a|<\varepsilon_1. \hspace{2cm} {\color{red}(*)}\]

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=b \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_2>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_2}^2 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}^2\quad \text{ implies } \quad|b_n-b|<\varepsilon_2.\hspace{2cm}{\color{blue}(*)}\]

We begin by observing that \[\begin{aligned} |a_nb_n-ab|&=|a_nb_n-ab_n+ab_n-ab| \\&\leq |b_n(a_n-a)|+|a(b_n-b)|\\ &\leq |b_n||a_n-a|+|a||b_n-b|. \end{aligned}\]

But \(|a| \leq |a_n-a|+|a_n|\) thus \[\begin{aligned} |a_nb_n-ab| &\leq |b_n||a_n-a|+|b_n-b|(|a_n-a|+|a_n|)\\&\leq (|b_n|+|b_n-b|)|a_n-a|+|b_n-b||a_n|. \end{aligned}\]

Since \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a\) and \(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=b\) then there are \(M_1, M_2>0\) such that \[|a_n| \leq M_1 \quad \text{ and } \quad |b_n| \leq M_2 \quad \text{ for all } \quad n\in\mathbb N.\] Consequently \[|a_nb_n-ab| \leq (M_2+|b_n-b|)|a_n-a|+M_1|b_n-b|.\]

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary but fixed. We apply (*) with \({\color{red}\varepsilon_1=\frac{\varepsilon}{2(M_2+1)}}\) and (*) with \({\color{blue}\varepsilon_2=\min\big\{\frac{\varepsilon}{2M_1},1 \big\}}\), which implies respectively

\[\begin{aligned} &n \geq N_{\varepsilon / 2}^1 \quad \text{ implies } \quad |a-a_n|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2(M_2+1)},\\ &n \geq N_{\varepsilon / 2}^2\quad \text{ implies } \quad|b-b_n|<\min\Big\{\frac{\varepsilon}{2M_1},1 \Big\}. \end{aligned}\]

Thus taking \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}=\max\left(N_{\varepsilon_1}^1,N_{\varepsilon_2}^2 \right)\) we see that \[\begin{aligned} |a_nb_n-ab| &\leq {\color{brown}(M_2+|b_n-b|)|a_n-a|}+{\color{purple}M_1|b_n-b|} \\ &< {\color{brown}\Big(M_2+\min\Big\{\frac{\varepsilon}{2M_1},1\Big\}\Big)\frac{\varepsilon}{2(M_2+1)}}+{\color{purple}M_1 \min\Big\{\frac{\varepsilon}{2M_1},1\Big\}}\\ &\leq (M_2+1)\frac{\varepsilon}{2(M_2+1)}+M_1\frac{\varepsilon}{2M_1} \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2}+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon. \end{aligned}\]

Since \(\varepsilon>0\) was arbitrary we proved that \[\lim_{n \to \infty}a_nb_n=ab.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_1>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_1}^1 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that

\[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_1}^1\quad \text{ implies } \quad |a_n-a|<\varepsilon_1. \hspace{2cm} {\color{red}(*)}\]

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=b \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_2>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_2}^2 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}^2\quad \text{ implies } \quad|b_n-b|<\varepsilon_2.\hspace{2cm}{\color{blue}(*)}\]

By (iii) it suffices to prove that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=b\) implies \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{1}{b_n}=\frac{1}{b}\] whenever \(b_n,b \neq 0\) for \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary. Note that \[\left|\frac{1}{b_n}-\frac{1}{b}\right|=\frac{|b_n-b|}{|b_n||b|}.\]

Applying (*) with \({\color{blue}\varepsilon_2=\min \Big\{\frac{|b|}{2},\frac{\varepsilon|b|^2}{2}\Big\}}\) one has \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}\quad \text{ implies } \quad|b_n-b|<\varepsilon_2.\]

But \(\frac{|b|}{2} > |b_n-b| \geq |b|-|b_n|\), hence \[|b|-|b_n|<\frac{|b|}{2} \quad \text{ for all } \quad n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}.\]

Consequently \(\frac{|b|}{2}<|b_n|\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). This shows that \[\left|\frac{1}{b_n}-\frac{1}{b}\right|=\frac{|b_n-b|}{|b_n||b|}<\frac{2|b_n-b|}{|b|^2} \quad \text{ for all }\quad n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}.\]

Furthermore, for \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon_2}\) we also know that \[\begin{aligned} \left|\frac{1}{b_n}-\frac{1}{b}\right|<\frac{2|b_n-b|}{|b|^2}< \frac{2\varepsilon_2}{|b|^2} \leq \frac{2\varepsilon|b|^2}{2|b|^2}=\varepsilon. \end{aligned}\]

Thus \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{1}{b_n}=\frac{1}{b}.\] This completes the proof of the Theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Order limit theorem

Order limit theorem. Assume that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a\) and \(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=b\).

If \(a_n \geq 0\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), then \(a \geq 0\).

If \(a_n \leq b_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), then \(a \leq b\).

If there is \(c \in \mathbb{R}\) so that \(c \leq b_n\) for each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), then \(c \leq b\). Similarly, if \(a_n \leq c\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), then \(a \leq c\).

Proof of (i). Assume for contradiction that \(a<0\). We know that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a \iff\) for every \(\varepsilon_0>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon_0} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon_0}\quad \text{ implies } \quad |a_n-a|<\varepsilon_0. \hspace{2cm} {\color{red}(*)}\] Applying (*) with \(\varepsilon_0=|a|\) one sees \[|a_n-a|<|a| \quad \text{ for all }\quad n \geq N_{\varepsilon_0}.\]

Hence \(a_n<0\) for all \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon_0}\) which is impossible since \(a_n \geq 0\) for all \(n \in\mathbb{N}\). Thus we must have \(a \geq 0\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof of (ii). \(\lim_{n \to \infty}(b _n-a_n)=b-a\). But \(b_n-a_n \geq 0\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) thus \(b-a \geq 0\) by \((i)\) and we are done. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof of (iii). Take \(a_n=c\) (or \(b_n=c\)) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and apply (ii).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$