13. Toeplitz theorem and applications; Exponential and logarithm function; Bolzano--Weierstrass theorem PDF

Toeplitz theorem and applications

Toeplitz theorem

Toeplitz theorem. Let \(\{c_{n,k}\;:\; 1 \leq k \leq n, n \geq 1\}\) be an array or real numbers such that

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}c_{n,k}=0\) for \(k \in \mathbb{N}\).

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}\sum_{k=1}^{n}c_{n,k}=1\).

There is \(C>0\) such that \[\sup_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\sum_{k=1}^{n}|c_{n,k}| \leq C.\]

Then for any sequence \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) so that \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a\) its transformated sequence \[{\color{red}b_n=\sum_{k=1}^{n}c_{k,n}a_k}\] also converges and \(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=a\).

Toeplitz theorem - example

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & & & & & & & &\ldots \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} & & & & & & &\ldots \\ \frac{1}{3} & \frac{1}{3} & \frac{1}{3} & & & & & &\ldots \\ \frac{1}{4} & \frac{1}{4} & \frac{1}{4} & \frac{1}{4} & & & & &\ldots \\ \frac{1}{5} & \frac{1}{5} & \frac{1}{5} & \frac{1}{5} & \frac{1}{5} & & & &\ldots \\ \frac{1}{6} & \frac{1}{6} & \frac{1}{6} & \frac{1}{6} & \frac{1}{6} & \frac{1}{6} & & &\ldots \\ \frac{1}{7} & \frac{1}{7} & \frac{1}{7} & \frac{1}{7} & \frac{1}{7} & \frac{1}{7} & \frac{1}{7} & &\ldots \\ \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{8} &\ldots \\ \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots &\ldots \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]

If \(a_n=a\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), then \[\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=a\lim_{n \to \infty}c_{n,k}=a.\]

Thus, it suffices to consider the case when \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=0\).

Then, for any \(m>1\) and \(n \geq m\):

(*). \[|b_n-0|=\left|\sum_{k=1}^nc_{n,k}a_k\right| \leq {\color{red}\sum_{k=1}^{m-1}|c_{n,k}||a_k|}+{\color{blue}\sum_{k=m}^{n}|c_{n,k}||a_k|}.\]

Since \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=0\) thus for any \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(N_{\varepsilon}^1 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[n \geq N_{\varepsilon}^1 \quad \text{ implies } \quad |a_n|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2C}.\]

Of course \(|a_n| \leq M\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and some \(M>0\). If follows from (i) that there is \(N_{\varepsilon}^{2} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}^2\) implies

\[\sum_{k=1}^{N_{\varepsilon}^1-1}|c_{n,k}|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2M}.\] Applying (*) with \(m=N_{\varepsilon}^1\) we obtain \[\begin{aligned} |b_n| \leq {\color{red}M\sum_{k=1}^{N_{\varepsilon}^1-1}|c_{n,k}|}+{\color{blue}\frac{\varepsilon}{2C}\sum_{k=N_{\varepsilon}^1}^{n}|c_{n,k}|} \leq {\color{red}\frac{\varepsilon}{2}}+{\color{blue}\frac{\varepsilon}{2}}=\varepsilon \end{aligned}\] for all \(n \geq \max(N_{\varepsilon}^1,N_{\varepsilon}^2)\). Thus we conclude \[\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=0.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proposition

Proposition. Let \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and \((b_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) be two sequences such that

\(b_n >0\), \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(\lim_{n \to \infty}b_k=+\infty\),

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{a_n}{b_n}=g\).

then \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{a_1+\ldots+a_n}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}=g.\]

Proof. We apply Toeplitz theorem to the sequence \((a_n / b_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) with \[c_{n,k}=\frac{b_k}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}.\]

Then for (i) we note \[\lim_{n \to \infty}c_{n,k}=\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{b_k}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}=b_k\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{1}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}=b_k \cdot 0=0.\] For (ii) we have \[\sum_{k=1}^n c_{n,k}=\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{b_k}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}=\frac{b_1+\ldots+b_n}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}=1.\]

Since \(b_k>0\) (iii) follows from (ii). Thus by Toeplitz theorem we conclude \[g=\lim_{n \to \infty}\sum_{k=1}^{n}c_{n,k}\frac{a_k}{b_k}= \lim_{n \to \infty}\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{a_k {\color{red}b_k}}{(b_1+\ldots+b_n){\color{red}b_k}}= \lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{a_1+\ldots+a_n}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proposition. Let \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and \((b_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) be two sequences such that

\(b_n>0\), \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\sum_{k=1}^nb_k=+\infty\).

\(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=a\).

Then \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{a_1b_1+\ldots+a_nb_n}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}=a.\]

Proof. We apply Toeplitz theorem with the sequence \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and \[c_{n,k}=\frac{b_k}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}.\]

Then \[a=\lim_{n \to \infty}\sum_{k=1}^nc_{n,k}a_k=\lim_{n \to \infty}\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{a_kb_k}{b_1+\ldots+b_n} =\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{a_1b_1+\ldots+a_nb_n}{b_1+\ldots+b_n}. \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Stolz theorem

Stolz theorem. Let \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\), \((y_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) be two sequences so that

\((y_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) strictly increases to \(+\infty\), i.e. \(y_n<y_{n+1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(\lim_{n \to \infty}y_n=+\infty\).

Also we have \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{x_n-x_{n-1}}{y_n-y_{n-1}}=g.\]

then \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{x_n}{y_n}=g.\]

Proof. Apply the previous proposition with \[a_n=\frac{x_n-x_{n-1}}{y_n-y_{n-1}}, \quad \text{ and } \quad b_n=y_n-y_{n-1}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Exponential function

Euler’s number

We know that

\[\lim_{n \to \infty}\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)^n=e^x.\]. for any \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Also

\[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n!}=e.\].

Theorem. Let \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), then \[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{x^n}{n!}=e^x.\]

Proof. Let \(S_n=\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{x^k}{k!}\), then by the binomial theorem we may write

\[\begin{aligned} \left|S_n-\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)^n\right|&=\left|\sum_{k=2}^n \left(1-\left(1-\frac{1}{n}\right)\cdot \ldots \cdot \left(1-\frac{k-1}{n}\right)\right)\frac{x^k}{k!}\right|\\&\leq \sum_{k=2}^n \left(1-\left(1-\frac{1}{n}\right)\cdot \ldots \cdot \left(1-\frac{k-1}{n}\right)\right)\frac{|x|^k}{k!}. \end{aligned}\] Let us also note that \[\left(1-\frac{1}{n}\right)\cdot \ldots \cdot \left(1-\frac{k-1}{n}\right) \geq 1-\sum_{j=1}^{k-1}\frac{j}{n}=1-\frac{k(k-1)}{n}\] for \(2 \leq k \leq n\).

Thus \[\left|S_n-\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)^n\right| \leq \sum_{k=2}^n\frac{k(k-1)}{2n}\frac{|x|^k}{k!}= \frac{1}{2n}\sum_{k=2}^{n}\frac{|x|^k}{(k-2)!}.\]

Using the Stolz theorem \[\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{1}{2n}\sum_{k=2}^{n}\frac{|x|^k}{(k-2)!}=\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{1}{2}\frac{|x|^n}{(n-2)!}=0.\]

Thus \[\lim_{n \to \infty}S_n=\lim_{n \to \infty}\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)^n=e^x\] as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Exponential function

Exponential function. The function \(E:\mathbb{R} \to (0,\infty)\) defined by \(E(x)=e^x\) is called the exponential function.

Properties of exponential function.

For all \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\) one has \[e^{x+y}=e^xe^y.\]

If \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n = a\), then \(\lim_{n \to \infty}e^{a_n}=e^{a}\).

\(E\) is one-to-one and onto. Thus the inverse for \(E\) exists.

Natural logarithm

Natural logarithm. The inverse of \(E\) exists. It will be denoted by \(E^{-1}:(0,\infty) \to \mathbb{R}\), \[E^{-1}(x)=\ln(x)=\log(x)\] and it is called the natural logarithm.

Simple properties of natural logarithm.

\(\log(x)\) is increasing.

For \(x,y \in (0,\infty)\) we have \[\log(xy)=\log(x)+\log(y).\]

We also have \(x^{\alpha}=e^{\alpha \log(x)}\) for all \(\alpha \in \mathbb{R}\).

Proposition

Proposition. For \(x>0\) we have \[\frac{x}{x+2}<\log(x+1)<x.\]

Proof. We prove that for \(0<x<m\) with \(m \in \mathbb{N}\), we have \[\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)^n<e^x<\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)^{n+m}.\]

thus \[n\log\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)<x<(n + m)\log\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right).\]

Hence \[\frac{x}{n+m}<\log\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)<\frac{x}{n} \quad \text{ if } \quad m>x.\]

Taking \(n=1\) we obtain \[\log(1+x)<x \quad \text{ for all } \quad x>0.\]

Now set \(m=\lfloor x\rfloor+1>x\), then \[\log\left(1+\frac{x}{n}\right)>\frac{\frac{x}{n}}{2+\frac{x}{n}}.\]

Thus for \(n=1\) we obtain \[\log(1+x)>\frac{x}{2+x}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark. In fact, for every \(x>0\) the following inequality holds \[\frac{x}{x+1}<\log(x+1)<x.\]

Euler–Mascheroni constant

Divergence of harmonic series. \[\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n}=+\infty.\]

Theorem. The sequences \[{\color{blue}a_n=\sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{k}-\log(n) \quad \text{ and } \quad b_n=\sum_{k=1}^{n}\frac{1}{k}-\log(n)}\] are increasing and decreasing respectively and bounded, and \[\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=\gamma.\] where \(\gamma\) is known as the Euler (or Euler–Mascheroni) constant.

Remark.

It is not even known whether \(\gamma\) is irrational.

\(\gamma\) is called Euler-Mascheroni constant, and \(\gamma \simeq 0,5772\ldots\).

Proof. We know \[\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)^n<e<\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)^{n+1}\] thus \[n \log\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)<1<(n+1)\log\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right),\] and consequently \[\log\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)<\frac{1}{n},\] \[\log\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)>\frac{1}{n+1}.\]

Thus \[\begin{aligned} a_{n+1}-a_n=\sum_{k=1}^{n}\frac{1}{k}-\log(n+1)-\sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{k}+\log(n)= \frac{1}{n}-\log\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)>0. \end{aligned}\] Hence \((a_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\) is increasing. Similarly,

\[\begin{aligned} b_{n+1}-b_n=\frac{1}{n+1}-\log\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)<0, \end{aligned}\] thus \((b_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\) is decreasing. Also it is clear \[a_1 \leq a_n \leq b_n \leq b_1.\] Thus by the (MCT) the limits exist \[\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n=\lim_{n \to \infty}b_n=\gamma,\] since \(b_n=a_n+\frac{1}{n}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem

Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem

Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem. Every bounded sequence contains convergent subsequence.

Proof. Let \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) be bounded. Then there is \(M>0\) such that \[|a_n| \leq M\quad \text{ for all } \quad n \in \mathbb{N}.\]

Thus \(a_n \in [-M,M]\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

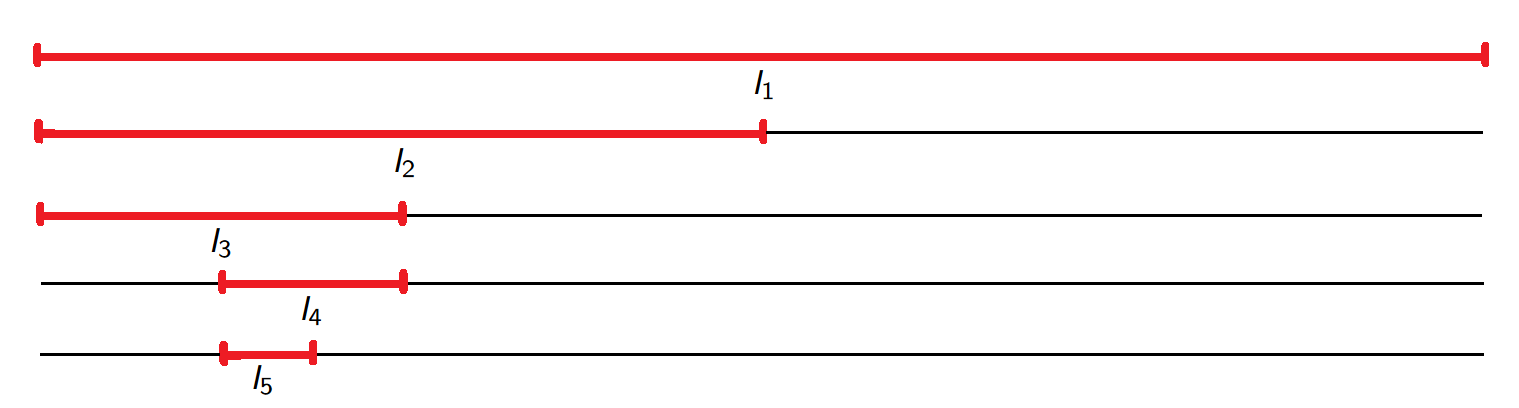

Step 1. Divide \([-M,M]\) into two closed intervals \([-M,0]\), \([0,M]\). We can assume (wlog) that \(I_1=[0,M]\) contains infinitely many elements of \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\). Moreover, the length of \(I_1\) is \(M\).

Step 2. Divide \(I_1\) into two closed intervals of the same length and select the one which contains infinitely many elements of \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\). Call it \(I_2 \subset I_1\) and note that has length \(\frac{M}{2}\).

Step 3. Proceeding inductively as above we obtain a sequence of decreasing closed intervals \[I_1 \supset I_2 \supset I_3 \supset I_4 \supset \ldots\] where each \(I_k\) contains infinitely many elements of \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and has length \(\frac{M}{2^{k-1}}\).

Step 4. By the Nested Intervals Property \(\bigcap_{k=1}^{\infty}I_k \neq \varnothing\). In fact, \[\bigcap_{k=1}^{\infty}I_k =\{x\} \quad \text{ for some }\quad x \in \mathbb{R}.\] Now for each \(k \in \mathbb{N}\) select an element \(a_{n_k} \in I_{k}\) so that \[n_1<n_2<\ldots< n_k<\ldots\] where \(a_{n_1}\) is any element of \(I_1\).

Step 5. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) and choose \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \[\frac{M}{2^{k-1}}<\varepsilon \quad \text{ for }\quad k \geq N_{\varepsilon}.\] Then for every \(k \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) we have \[|a_{n_k}-x|\leq \frac{M}{2^{k-1}}<\varepsilon,\] thus \(\lim_{n \to \infty}a_{n_k}=x\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem - example

Example. Let us consider a sequence \[a_n=(-1)^n.\] It in NOT convergent, but the subsequence \((-1)^{2n}=1\) converges to \(1\).