17. Complete spaces; and Compact sets PDF

Proposition

Proposition. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space, \(E \subseteq X\) is closed iff for every sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq E\) such that \(x_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ x \in X\) we have \(x \in E.\)

Proof. (\(\Longrightarrow\)) Suppose that \(E\) is closed and consider \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq E\) such that \(x_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ x \in X\). We have to show that \(x \in E\). Observe that \[B(x,r) \cap E \neq \varnothing \quad \text{ for any }\quad r>0.\] But \(x_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ x\) iff \(x_n \in B(x,r)\) for all but finitely many \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), and consequently we conclude that \(x \in {\rm cl\;}(E)\), hence \(x\in E\).

(\(\Longleftarrow\)) Conversely, if \(x \in {\rm cl\;}(E)\) then there is a sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq E\) so that \(x_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ x \in {\rm cl\;}(E)\subseteq X\) thus by our assumption \(x \in E\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem

Theorem. The subsequential limits of a sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) in a metric space \((X,\rho)\) form a closed subset of \(X\).

Proof. Let \(E^{*}\) be the set of subsequential limits of \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and let \(q\) be an accumulation point of \(E^{*}\). We will show that \(q \in E^{*}\).

Choose \(n_1 \in \mathbb{N}\) so that \(E^*\ni x_{n_1} \neq q\) (if no such point exists then \(E^{*}\) has only one point and there is nothing to prove). Set \[\delta=\rho(x_{n_1},q)>0.\]

Suppose that \(n_1,\ldots,n_{i-1}\) have been chosen. Since \(q\) is an accumulation point of \(E^{*}\) there is \(x \in E^{*}\) so that \[{\color{red}\rho(x,q)<\delta2^{-i-1}}.\]

Since \(x \in E^{*}\) there is \(n_i>n_{i-1}\) such that \({\color{blue}\rho(x,x_{n_i})<\delta 2^{-i-1}}\).

Hence, by the triangle inequality \[\rho(q,x_{n_i}) \leq {\color{red}\rho(q,x)}+{\color{blue}\rho(x,x_{n_i})}<{\color{red}\delta 2^{-i-1}}+{\color{blue}\delta 2^{-i-1}}=\delta 2^{-i}.\]

This means that \((x_{n_i})_{i \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges to \(q\), i.e. \[\lim_{i\to \infty}x_{n_i}=q \quad \iff \quad \lim_{i\to \infty}\rho(x_{n_i}, 0)=0\] thus \(q \in E^{*}\).

In fact, we have shown that \[{\rm acc\;}(E^*) \subseteq E^{*},\] which means that \(E^{*}\) is closed. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cauchy sequences and complete spaces

Cauchy sequences

Cauchy sequence. A sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a metric space \((X,\rho)\) is said to be a Cauchy sequence if for every \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \[m,n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\quad \text{ implies } \quad \rho(x_{m},x_{n})<\varepsilon.\]

Complete spaces. A subset of a metric space \((X,\rho)\) is called complete if every Cauchy sequence in \(E\) converges and its limit is in \(E\).

Complete spaces - examples

Example 1. The set of real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\) is complete.

Example 2. The open unit interval \((0,1)\) is not complete space in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Indeed, let \(x_n=\frac{1}{n}\) for \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), then \(x_n \in (0,1)\) and \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is Cauchy in \((0,1)\), but \(0\), which is the limit of \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is not in \((0,1)\).

Example 3. \([0,1]\) is complete space in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Some facts

Fact 1. If \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is Cauchy in a metric space \((X,\rho)\) then \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is bounded.

Fact 2. If \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a Cauchy sequence in a metric space \((X,\rho)\) and \(\lim_{k \to \infty}\rho(x_{n_k},x)=0\) for some \((x_{n _k})_{k \in \mathbb{N}}\), then \[\lim_{n \to \infty} \rho(x_n,x)=0.\]

Proposition. A closed subset of a complete metric space is complete and a complete subset of an arbitrary metric space is closed.

Proof. If \((X,\rho)\) is complete, \(E \subseteq X\) is closed and \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a Cauchy sequence in \(E\), then \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) has a limit in \(X\). But \({\rm cl\;}(E)=E\), thus \(x \in {\rm cl\;}(E)\), so \(x \in E\).

If \(E \subseteq X\) is complete and \(x \in {\rm cl\;}(E)\) then we know that there exists \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq E\) converging to \(x\). But \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is Cauchy so its limit lies in \(E\), thus \({\rm cl\;}(E)=E\) as desired.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark. In the second part of the proof we have used the fact that if \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) converges (say to \(x\) in a metric space \((X,\rho)\)) then \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is Cauchy.

Cantor intersection theorem

Cantor intersection theorem. A metric space is complete iff for every decreasing sequence \[F_1 \supseteq F_2 \supseteq F_3 \supseteq \ldots\] of nonempty closed sets in \(X\) with \({\rm diam\;}(F_n) \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0\), one has \[{\color{blue}\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}F_n=\{x_0\} \quad \text{ for some }\quad x_0 \in X}.\]

Assume that \((X,\rho)\) is complete.

Let \((F_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) be such that \(F_1 \supseteq F_2 \supseteq F_3 \supseteq \ldots\) and \({\rm diam\;}(F_n) \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0\).

Choose \(x_n \in F_n\), let \(\varepsilon>0\) and pick \(N_{\varepsilon} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \({\rm diam\;}(F_n)<\varepsilon\) for all \(n \geq N_{\varepsilon}\). Note that for \(n \geq m \geq N_{\varepsilon}\) we have

\[x_n \in F_n \subseteq F_m,\]

so \[\rho(x_n,x_m) \leq {\rm diam\;}(F_m)<\varepsilon.\]

This ensures that \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a Cauchy sequence and, consequently, converges to some \(x_0 \in X\). Since each \(F_n\) is closed then \(x_0 \in F_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), thus \(x_0 \in \bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}F_n\).

Suppose there is \(y \neq x_0\) so that \(y \in \bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}F_n\), then

\[0<\rho(x_0,y) \leq {\rm diam\;}(F_n) \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0,\] contradiction. Thus \(\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}F_n =\{x_0\}\).

To prove the converse implication assume that \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a Cauchy sequence.

Let \[{\color{red}F_n={\rm cl\;}\left(\{x_m\;:\; m \geq n\}\right).}\]

Fact. \[{\rm diam\;}(E)={\rm diam\;}({\rm cl\;}(E)).\]

We see that \(F_1 \supseteq F_2 \supseteq F_3 \supseteq \ldots\) and

\[{\rm diam\;}(F_n)={\rm diam\;}\left(\{x_m\;:\;m \geq n\}\right) \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0.\]

Thus \(\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}F_n=\{x_0\}\) for some \(x_0 \in X\).

Finally, we conclude \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\rho(x_n,x_0)=0\) as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Compact sets

Coverings and compact sets

Coverings. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space.

If \(E \subseteq X\) and \((V_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a family of sets such that \(E \subseteq \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}V_{\alpha}\), then \((V_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is called a cover of \(E\) and \(E\) is said to be covered by the \(V_{\alpha}\)’s.

If additionally each \(V_{\alpha}\) is open \((V_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is called an open cover of \(E\).

Heine–Borel property. A subset \(K\) of a metric space \((X,\rho)\) is said to be compact if every open cover of \(K\) contains a finite subcover. More explicitly, if \((V_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is an open cover of \(K\) then there are finitely many \(\alpha_1,\alpha_2,\ldots,\alpha_n \in A\) such that \[K \subseteq \bigcup_{j=1}^{n}V_{\alpha_j}.\]

Compact sets - examples

Example 1. Every finite subset of \(\mathbb{R}\) is compact.

Example 2. \(K=\{\frac{1}{n}\;:\;n \in \mathbb{N}\} \cup \{0\}\) is compact in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Indeed, let \((V_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) be an open cover of \(K\), then there is \(\alpha_0 \in A\) such that \(0 \in V_{\alpha_0}\) since \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\frac{1}{n}=0\) and \(V_{\alpha_0}\) is open thus it contains all but finitely many \(\frac{1}{n}\)’s. In other words, there is \(n_0 \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(n \geq n_0\) implies \(\frac{1}{n} \in V_{\alpha_0}\). Then, for each \(j \in \{1,2,\ldots,n_0-1\}\) we can pick \(\alpha_j \in A\) so that \(\frac{1}{j}\in V_{\alpha_j}\) and we see

\[K \subseteq \bigcup_{j=0}^{{\color{red}n_0}}V_{\alpha_j}.\]

Theorem

Theorem. Compact subsets of metric spaces are closed.

Proof. Let \(K\) be compact subset of a metric space \(X\).

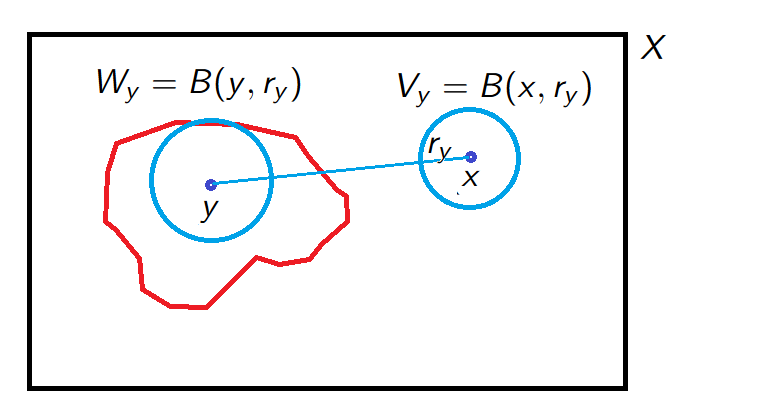

We shall prove that \(K^c\) is open in \(X\). Let \(x \in X \setminus K\). If \(y \in K\), let \[V_{y}=B(x,r_y) \quad \text{ and }\quad W_y=B(y,r_y),\] where \(r_y<\frac{1}{2}\rho(x,y)\), then \({\color{red}V_{y} \cap W_y = \varnothing}\).

Since \(K\) is compact \(K \subseteq \bigcup_{y \in K}W_y\), then we can find \(y_1,\ldots,y_n \in K\) so that \[{\color{red}K \subseteq \bigcup_{j=1}^nW_{y_j}=W}.\]

If \(V=V_{y_1} \cap \ldots \cap V_{y_n}\) then \(V\) is an open set containing \(x\) and

\[V \cap W = \varnothing.\]

Hence \(x \in V \subseteq W^c \subseteq K^c\) thus \(x\) is an interior point of \(K^c\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem. Closed subsets of compact sets are compact.

Proof. Suppose that \(F \subseteq K \subseteq X\) and \(F\) is closed in \(X\) and \(K\) is compact.

Let \((V_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) be an open cover of \(F\). Observe that \[F \subseteq K \subseteq \underbrace{\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}V_{\alpha}}_{{\color{red} F\subseteq }} \cup \underbrace{F^c}_{\text{open}}.\]

The set \(K\) is compact thus there is a finite subcover of \[(V_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A} \cup \{F^c\}\] that covers \(K\).

But \(F \subseteq K\) hence this is also a finite subcover of \(F\) upon removing \(F^c\) as desired.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theorem. If \((K_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a collection of compact sets of a metric space \((X,\rho)\) such that the intersection of every finite subcollection of \((K_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is non-empty then \[\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}K_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing.\]

Proof. Fix a member \(K_{\alpha_0}\) of \((K_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) and set \(G_{\alpha}=K_{\alpha}^c\).

Suppose that \[\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}K_{\alpha}=K_{\alpha_0} \cap \left(\bigcap_{\alpha \in A \setminus \{\alpha_0\}}K_{\alpha}\right)=\varnothing.\]

Then \[K_{\alpha_0} \subseteq \bigcup_{\alpha \in A \setminus \{\alpha_0\}}G_{\alpha}.\]

Since \(K_{\alpha_0}\) is compact there are \(\alpha_1,\ldots ,\alpha_n \in A\) so that \[K_{\alpha_0} \subseteq \bigcup_{j=1}^n G_{\alpha_j}.\]

Hence \[K_{\alpha_0} \cap K_{\alpha_1} \cap \ldots \cap K_{\alpha_n}=\varnothing,\] which is a contradiction. So we must have \[\bigcap_{\alpha \in A}K_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing.\] as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Perfect sets

Accumulation and isolated points

Accumulation point. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space, \(x \in X\) is called an accumulation point of \(E \subseteq X\) if for every open set \(U \ni x\) we have \[(E \setminus \{x\}) \cap U \neq \varnothing.\]

An accumulation point \(x\) of \(E \subseteq X\) is sometimes also called a limit point of \(E\) or a cluster point of \(E\).

Isolated point. A point \(x \in E\) is called an isolated point of \(E\) if it is not an accumulation point of \(E\).

Perfect sets

Perfect sets. We say that a subset \(E\) of a metric space \((X,\rho)\) is perfect if \(E\) is closed and every point of \(E\) is its limit point or equivalently \[E={\rm acc\;}E.\]

Theorem. Let \(\varnothing \neq P \subseteq \mathbb{R}^k\) be a perfect set. Then \(P\) is uncountable.

In the proof we will use a very useful proposition:

Proposition. Every closed and bounded set of \(\mathbb{R}^k\) is compact.

The proof of this proposition will be provided next time.

Proof. Since \(P\) has limit points, \(P\) must be infinite. In fact, for every \(x \in P\) and \(r>0\) \[B(x,r) \cap P \quad \text{ is infinite.}\]

Suppose not, i.e. there is \(x_0 \in P\) and \(r_0>0\) such that \[B(x_0,r_0) \cap P=\{x_1,\ldots,x_n\}.\]

Consider \[\rho(x_0,x_1), \ldots, \rho(x_0,x_n)\] and let \[r=\min_{1 \leq i \leq n}\rho(x_0,x_i)>0.\]

Then \[B(x_0,r) \cap P=\varnothing,\] thus \(x_0\) is not a limit point, contradiction.

Now we can assume \({\rm card\;}(P) \geq {\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\). Suppose for a contradiction that \({\rm card\;}(P)={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{N})\), i.e. \(P=\{x_1,x_2,\ldots\}\).

Let \(V_1=B(x_1,r)\), then of course \(V_1 \cap P \neq \varnothing\). Suppose that \(V_n\) has been constructed so that \(V_n \cap P \neq \varnothing\).

Since every point of \(P\) is a limit point of \(P\) there is an open set \(V_{n+1}\) such that

\({\rm cl\;}(V_{n+1}) \subseteq V_{n}\),

\(x_{n+1} \not\in {\rm cl\;}(V_{n+1})\),

\(V_{n+1} \cap P \neq \varnothing\).

Let \(K_n={\rm cl\;}(V_n) \cap P\), this set is closed and bounded, thus compact. Since \(x_{n} \not\in K_{n+1}\), no point of \(P\) lies in \(\bigcap_{n=1}^{\infty}K_n\), but \(K_n \subseteq P\), so \[\bigcap_{n=1}^{\infty}K_n = \varnothing.\]

On the other hand, \(K_n \neq \varnothing\), compact, and \(K_{n+1} \subseteq K_n\), and the family \(K_n\) has a finite intesection property, i.e. any finite intersection of members of \((K_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is nonempty,

\[K_{n_1} \cap \ldots \cap K_{n_k} \neq \varnothing.\]

Thus \[\bigcap_{n=1}^{\infty}K_n \neq \varnothing,\] which is a contradiction. Hence \(P\) must be uncountable. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Corollary. Every interval \([a,b]\) with \(a<b\), and also \(\mathbb{R}\) are uncountable.