24. Power series of trigonometric functions done right PDF

Trigonometric functions: sine and cosine

Discussion

Suppose that two functions \(f,g:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) obeying the following condition \[{\color{purple}(*)} \qquad \qquad f'=g, \qquad g'=-f, \qquad f(0)=0, \qquad g(0)=1 \qquad \text{exist.}\]

We will show that they are determined uniquely. Note that

\[f^2(x)+g^2(x)=1.\]

Indeed, differentiating \(f^2+g^2\) we obtain \[(f^2+g^2)'(x)=2(f'f+g'g)(x)=2(fg-fg)=0.\]

Hence \(f^2(x)+g^2(x)=C\), but \(f(0)=0\) and \(g(0)=1\), so \(C=1\).

Suppose that there are two functions \(f_1,g_1:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) obeying \[f_1'=g_1, \qquad g_1'=-f_1, \qquad f_1(0)=0, \qquad g_1(0)=1.\]

Our aim is to show that \(f=f_1\) and \(g=g_1\).

Note that \[{\color{red}(fg_1-f_1g)'}=f'g_1+fg_1'-f_1'g-f_1g'=gg_1-ff_1-gg_1+f_1f=0,\] and \[{\color{blue}(ff_1+gg_1)'}=f'f_1+ff_1'+g'g_1+gg_1'=gf_1+fg_1-fg_1-gf_1=0.\]

Hence \({\color{red}fg_1-f_1g}\) and \({\color{blue}ff_1+gg_1}\) are constant functions and we have \[\begin{aligned} \begin{cases} {\color{red}fg_1-f_1g=a} \ \ | \ \ \cdot {\color{brown}f} \\ {\color{blue}ff_1+g_1g=b} \ \ | \ \ \cdot {\color{brown}g}, \end{cases} \qquad \iff \qquad \begin{cases} {\color{red}f^2g_1-ff_1g=af} \\ {\color{blue}ff_1g+g_1g^2=bg}. \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

Adding the equations and using \(f^2+g^2 \equiv 1\) we get \({\color{brown}g_1=af+bg}.\)

Similarly \[\begin{aligned} \begin{cases} {\color{red}fg_1-f_1g=a} \ \ | \ \ \cdot {\color{violet}g} \\ {\color{blue}ff_1+g_1g=b} \ \ | \ \ \cdot {\color{violet}f}, \end{cases} \qquad \iff \qquad \begin{cases} {\color{red}fgg_1-f_1g^2=ag} \\ {\color{blue}f^2f_1+g_1gf=bf}. \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

Subtracting the equations and using \(f^2+g^2 \equiv 1\) we get \({\color{violet}f_1=bf-ag}.\)

Hence \[\begin{aligned} \qquad\qquad\qquad \begin{cases} {\color{brown}g_1=af+bg} \\ {\color{violet}f_1=bf-ag}. \end{cases} \qquad \qquad\qquad\qquad (*) \end{aligned}\]

Using \(f(0)=f_1(0)=0\) and \(g(0)=g_1(0)=1\) we get \(a=0\), \(b=1\) and, finally, we conclude that \(f=f_1\), \(g=g_1\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Heuristics 1/2

If functions \(f,g:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) obeying the following condition \[{\color{purple}(*)} \qquad \qquad f'=g, \qquad g'=-f, \qquad f(0)=0, \qquad g(0)=1 \qquad \qquad\] exist, then they are differentiable infinitely many times.

Since \(f'=g\) and \(g'=-f\), thus \[\begin{gathered} {\color{red}f''=-f, \quad g''=-g,}\quad {\color{blue}f'''=-g, \quad g'''=f,} \quad {\color{violet}f^{(4)}=f, \quad g^{(4)}=g.} \end{gathered}\]

Using Taylor’s formula with Lagrange’s remainder at \(x_0=0\) one has \[\begin{aligned} f(x)=\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}x^k+r_n(x), \quad \text{ where }\quad r_n(x)=\frac{f^{(n+1)}(\theta x)}{(n+1)!}x^{n+1}.\\ g(x)=\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{g^{(k)}(0)}{k!}x^k+\widetilde{r}_n(x), \quad \text{ where }\quad \widetilde{r}_n(x)=\frac{g^{(n+1)}(\theta x)}{(n+1)!}x^{n+1}. \end{aligned}\]

Heuristics 2/2

Since \(f^2(x)+g^2(x)=1\), so \(|f(x)|, |g(x)| \leq 1\), and consequently \[|f^{(n)}(x)|\le 1\qquad \text{ and } \qquad |g^{(n)}(x)|\le 1,\] which implies \[|r_n(x)|\leq \frac{1}{(n+1)!}|x|^{n+1} \qquad \text{ and } \qquad |\widetilde{r}_n(x)|\leq \frac{1}{(n+1)!}|x|^{n+1}.\]

This in turn implies that \[\lim_{n\to \infty} |r_n(x)|=0\qquad \text{ and } \qquad \lim_{n\to \infty}|\widetilde{r}_n(x)|=0.\]

Therefore if \(f, g\) exist then they are defined as the power series \[{\color{red}f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!}x^{2n+1}}, \quad \text{ and } \quad {\color{blue}g(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n)!}x^{2n}}.\]

It make sense to define \[{\color{red}S(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!}x^{2n+1}}, \quad \text{ and } \quad {\color{blue}C(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n)!}x^{2n}}.\]

We show that \[S'(x)=C(x), \quad C'(x)=-S(x), \quad S(0)=0, \quad C(0)=1.\]

Obviously we have \(S(0)=0\) and \(C(0)=1\). We only have to show that \(S'(x)=C(x)\) and \(C'(x)=-S(x)\).

Indeed, to prove \(S'(x)=C(x)\), note that \[\begin{aligned} &\frac{1}{h}(S(x+h)-S(x))=\frac{1}{h}\left(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!}[(x+h)^{2n+1}-x^{2n+1}]\right) \\& =\frac{1}{h}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!} \left[\sum_{k=0}^{2n+1}{2n+1 \choose k}h^kx^{2n+1-k}-x^{2n+1}\right] \end{aligned}\]

Thus \[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{h}(S(x&+h)-S(x))\\ &= \frac{1}{h}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!} \sum_{k=1}^{2n+1}{2n+1 \choose k}h^kx^{2n+1-k} \\&=\frac{1}{h}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!} \left[x^{2n}(2n+1)+\sum_{k=2}^{2n+1}{2n+1 \choose k}h^kx^{2n+1-k}\right] \\&=\underbrace{\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n)!}x^{2n}}_{{\color{blue}C(x)}}+\underbrace{\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!} \sum_{k=2}^{2n+1}{2n+1 \choose k}h^{k-1}x^{2n+1-k}}_{{\color{purple}R(x)}}. \end{aligned}\]

Recalling that \[\begin{aligned} {\color{purple}R(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!} \sum_{k=2}^{2n+1}{2n+1 \choose k}h^{k-1}x^{2n+1-k}} \end{aligned}\]

Then if \(|h| \leq \frac{1}{2}\) one has \[\begin{aligned} |R(x)| &\leq |h|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{(2n+1)!}\sum_{k=0}^{2n+1}{2n+1 \choose k}|x|^{2n+1-k} \\& \leq |h|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{(|x|+1)^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!} \ _{\overrightarrow{n \to \infty}}\ 0. \end{aligned}\]

Hence \(S'(x)=C(x)\). Similarly \(C'(x)=-S(x)\).

Sine and Cosine functions

Theorem. There are unique functions \(S, C:\mathbb R\to \mathbb R\) such that \[S'(x)=C(x), \quad C'(x)=-S(x), \quad S(0)=0, \quad C(0)=1.\] In other words, the functions \(S, C\) satisfy condition (*), and they are given explicitly by the following formulas \[{\color{red}S(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!}x^{2n+1}}, \quad \text{ and } \quad {\color{blue}C(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n)!}x^{2n}}.\] They will be called respectively sine and cosine functions and will be denoted by \({\color{red}\sin(x)=S(x)}\) and \({\color{blue}\cos(x)=C(x)}\).

Properties of \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\)

Properties of \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\)

Properties. We have the following properties

\(\sin(x)^2+\cos(x)^2=1\),

\(\sin(-x)=-\sin(x)\),

\(\cos(-x)=\cos(x)\),

\(\sin(x+y)=\sin(x)\cos(y)+\cos(x)\sin(y)\),

\(\cos(x+y)=\cos(x)\cos(y)-\sin(x)\sin(y)\).

Proof of (a). It is clear since \(\sin(x)=S(x)\) and \(\cos(x)=C(x)\), and \(S(0)=0\), \(C(0)=1\) and \[S'(x)=C(x) \quad \text{ and }\quad C'(x)=-S(x).\]

Thus \[S(x)^2+C(x)^2=1.\]

Proof of (b). \[\sin(-x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!}(-x)^{2n+1}=-\sin(x).\] Proof of (c). \[\cos(-x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n)!}(-x)^{2n}=\cos(x).\]

Proof of (d) and (e). Taking \[f(x)=\sin(x), \qquad g(x)=\cos(x),\] and \[f_1(x)=\sin(x+y), \qquad g_1(x)=\cos(x+y),\] for a fixed \(y>0\). Proceeding as in the proof of the uniqueness we obtain

\[\begin{aligned} \qquad\qquad\qquad \begin{cases} {\color{brown}g_1=af+bg} \\ {\color{violet}f_1=bf-ag}. \end{cases} \qquad \qquad\qquad\qquad (*) \end{aligned}\] Solving this equation one sees that \[a=-\sin(y) \quad \text{ and }\quad b=\cos(y).\] This completes the proof of the theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Observations

Observation 1.

Since \((\sin(x))^2+(\cos(x))^2=1\) thus \[\begin{aligned} |\sin(x)| &\leq 1,\\ |\cos(x)| &\leq 1. \end{aligned}\]

Observations.

The derivative of \(\sin(x)\) at \(0\) is equal to \(1\), and the derivative is continuous. Thus it follows that the derivative of \(\sin(x)\) (which is \(\cos(x)\)) is positive for all numbers in some open interval containing \(0\).

Hence \(\sin(x)\) is strictly increasing in such an interval and strictly positive for all \(x>0\) in such an interval.

Observation 3.

We shall prove that there is \(x_0>0\) such that \(\sin(x_0)=1\), which means that \(\cos(x_0)=0\). Suppose that no such number exists.

Since \(\cos(x)\) is continuous, we conclude that \(\cos(x)\) cannot be negative for any value of \(x>0\) by the intermediate value theorem.

Hence \(\sin(x)\) is strictly increasing for all \(x>0\) and \(\cos(x)\) is strictly decreasing for all \(x>0\). Let \(a>0\). Then \[\begin{aligned} 0<\cos(2a)=\cos(a)^2-\sin(a)^2<\cos^2(a). \end{aligned}\]

By induction \[0<\cos(2^na)<(\cos(a))^{2^n} \quad \text{ for all }\quad n \in \mathbb{N}.\]

Hence \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\cos(2^na)=0\) since \(0<\cos(a)<1\).

Observation 3.

Since \(\cos(x)\) is strictly decreasing for \(x>0\) it follows that \(\cos(x)\) approaches to \(0\) as \(x \to \infty\), and hence \(\lim_{x \to \infty}\sin(x)=1\).

In particular, there is \(b>0\) so that \[\cos(b)<\frac{1}{4} \quad \text{ and }\quad \sin(b)>\frac{1}{2}.\]

Then \[0<\cos(2b)=\cos^2(b)-\sin^2(b)<\frac{1}{16}-\frac{1}{4}<-\frac{3}{16}<0,\] which is a contradiction.

Thus there is \(x_0>0\) so that \(\cos(x_0)=0\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Observation 4.

By Observation 3 \[A=\{x>0\;:\;\cos(x)=0\}=\{x>0\;:\;|\sin(x)|=1\} \neq \varnothing.\]

Let \(c=\inf A\). By the continuity of \(\cos(x)\) we see that \[\cos(c)=0\quad \text{ and }\quad |\sin(c)|=1.\] and \(c>0\).

We define \({\color{red}\pi=2c}\) thus \(c=\frac{\pi}{2}\).

Since \(c=\inf A\) thus there is no \(0 \leq x<\frac{\pi}{2}\) so that \[\cos(x)=0 \quad \text{ and }\quad |\sin(x)|=1.\]

Observation 4.

By the intermediate value theorem if follows that for \(0 \leq x<\frac{\pi}{2}\) we have \[0 \leq \sin(x)<1 \quad \text{ and }\quad 0<\cos(x) \leq 1\]

and \[\sin \frac{\pi}{2}=1, \qquad \cos \frac{\pi}{2}=0.\]

Consequently \[\sin(\pi)=0 \quad\text{ and } \quad \cos(\pi)=-1,\] \[\sin(2\pi)=0 \quad\text{ and } \quad \cos(2\pi)=1.\]

Observation 5. For all \(x\in\mathbb R\) one has

\(\sin(x+\frac{\pi}{2})=\cos(x)\),

\(\cos(x+\frac{\pi}{2})=-\sin(x)\),

\(\sin(x+\pi)=-\sin(x)\),

\(\cos(x+\pi)=-\cos(x)\),

\(\sin(x+2\pi)=\sin(x)\),

\(\cos(x+2\pi)=\cos(x)\).

The derivative of the \(\sin(x)\) is positive for \(0<x<\frac{\pi}{2}\). Hence \(\sin(x)\) is strictly increasing on \(0 \leq x \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\).

Similarly \(\cos(x)\) is strictly decreasing on this interval. For \(\frac{\pi}{2} \leq x \leq \pi\) we use the relation \(\sin(x)=\cos(x-\frac{\pi}{2}).\)

For \(\pi\) to \(2\pi\) we use \(\sin(x)=-\sin(x-\pi)\).

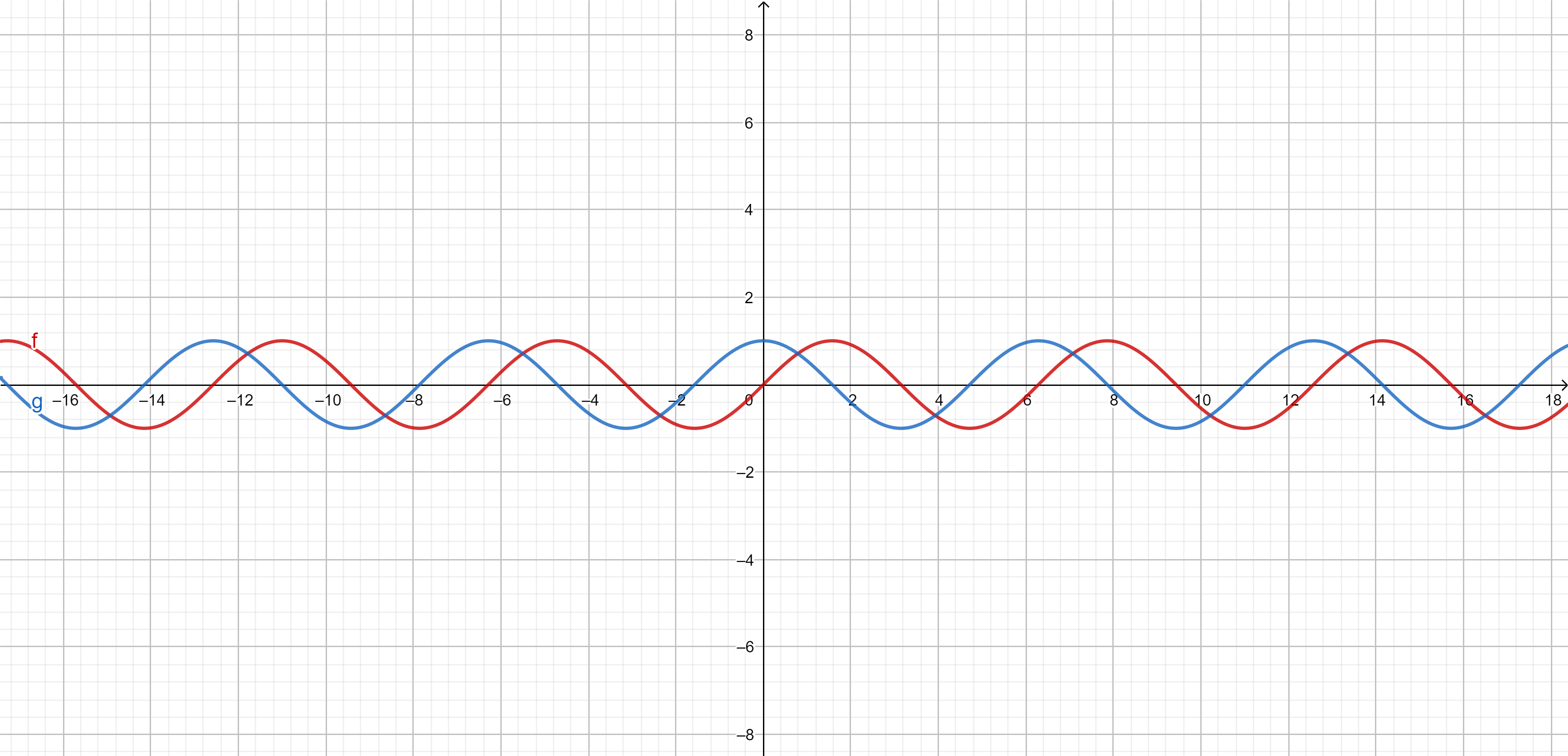

Graphs of \({\color{red}\sin(x)}\) and \({\color{blue}\cos(x)}\)

Now we can sketch the graphs of \({\color{red}\sin(x)}\) and \({\color{blue}\cos(x)}\):

Periodic functions

Periodic function. A function \(\phi:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) is periodic and a number \(s>0\) is called a period of \(\phi\) if \[\phi(x+s)=\phi(x) \quad \text{ for all }\quad x \in \mathbb{R}.\]

We see that \(2\pi\) is a period for \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\).

If \(s_1,s_2\) are periods for \(\phi\) then \(s_1+s_2\) is a period as well. Indeed, \[\phi(x)=\phi(x+s_1)=\phi(x+s_1+s_2).\]

If \(s>0\) is a period then \(-s\) is a period as well \[\phi(x)=\phi(x-s+s)=\phi(x-s).\]

Periods of \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\)

Let \(s\) be a period for \(\sin(x)\), then \(\{m \in \mathbb{N}\;:\; 2\pi m \leq s\} \neq \varnothing\). Let \[n=\max\{m \in \mathbb{N}\;:\;2\pi m \leq s\}.\]

Consider \(t=s-2\pi n\), then \(0 \leq t < 2\pi\), \(t\) is also a period of \(\sin(x)\). We must have \[\sin(t+0)=\sin(t)=0, \ \ \cos(0+t)=\cos(0)=1.\]

From the known values of \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\) for \(0 \leq x \leq 2\pi\) it may only happen when \(t=0\).

Thus \(s=2\pi n\).

Theorem

Theorem. Given a pair of numbers \(a,b\) such that \(a^2+b^2=1\), there exists a unique number \(0 \leq t \leq 2\pi\) such that \(a=\sin(t)\), \(b=\cos(t)\).

Proof. We consider four different cases according to \(a,b\) are \(\geq 0\) or \(\leq 0\). In any case \(|a| \leq 1\) and \(|b| \leq 1\).

Consider for instance the case \[-1 \leq a \leq 0 \quad \text{ and }\quad 0 \leq b \leq 1.\]

By the intermediate value theorem, there is exactly one value of \(t\) such that \(\frac{\pi}{2} \leq t \leq \pi\) and \(\cos(t)=a\).

We have \(b^2=1-a^2=1-\cos^2(t)=\sin^2(t)\).

Since \(\frac{\pi}{2} \leq t \leq \pi\) then \(\sin(t) \geq 0\) so \(b\) and \(\sin(t) \geq 0\) and \(b=\sin(t)\). Other cases follows similarly.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Limit \(\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}\)

Theorem. We have \[\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}=0.\]

Proof. We have \[\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sin(h)-\sin(0)}{h}=\sin'(0)=\cos(0)=1.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]