4. Consequences of the Axiom of Completeness; Decimals, Extended Real Number System PDF

Consequences of Axiom of completeness

Archimedian property of \(\mathbb{Q}\)

Archimedian property on \(\mathbb{Q}\).

Given any number \(x \in \mathbb{Q}\) there exists \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) satisfying \[n>x.\]

Given any rational number \(y>0\) there exists an \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) satisfying \[\frac{1}{n}<y.\]

The second property follows from the first one by taking \(x=\frac{1}{y}\). Thus it suffices to prove the first statement. If \(x\in \mathbb{Q}\) and \(x\le 0\), then there is nothing to do. Suppose that \(x>0\), then \(x=\frac{p}{q}\) for some \(p, q\in \mathbb{N}\). Consider the set \[A=\{n\in\mathbb{N}_0: n\le x\}.\] This set is nonempty since \(x>0\). We see that \(m\in A\) iff \(p-qm\ge0\). Consider now the set \[B=\{p-qn: n\in A\}\subset \mathbb N_0, \qquad \text{ and } \qquad B\neq \varnothing.\] By the well-ordering principle \(B\) contains the smallest element, say \(p-qm_0\) for some \(m_0\in A\). Thus for all \(n\in A\) we have \[p-qm_0\le p-qn \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad n\le m_0\le x.\] Now we see that \(x< m_0+1\) has desired property.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example

Example. Let \(E=\left\{\frac{1}{n}\;:\; n \in \mathbb{N}\right\}\subset\mathbb{Q}.\) Then \[\begin{aligned} \sup E&=1 \quad \text{ and } \quad 1 \in E,\\ \inf E&=0 \quad \text{ and } \quad0 \not\in E. \end{aligned}\]

We now show that \(\sup E=1\). Of course \(\frac{1}{n}\le 1\) for all \(n\in \mathbb N\) and \(1\in E\), which shows that \(\sup E=1\).

To prove that \(\inf E=0\) we note that \(\frac{1}{n}>0\) for all \(n\in \mathbb N\). Now take \(x\in\mathbb Q\) such that \(x>0\). By the Archimedian property we always find \(m\in \mathbb N\) such that \(0<\frac{1}{m}<x\) and we are done.

Axiom of completeness AoC

Let us recall the axiom of completeness.

Axiom of completeness AoC. Every non-empty set of real numbers that is bounded above has a least upper bound.

Our goal is to apply the axiom of completeness to study some properties of real numbers.

Application 1 - nested interval property

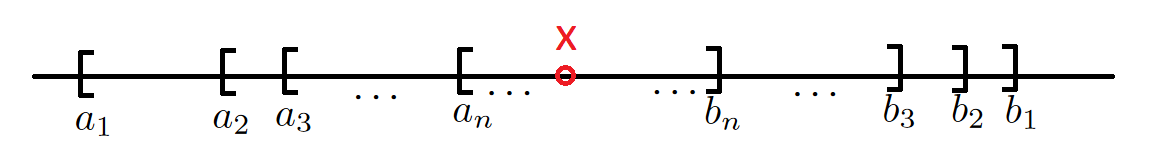

Nested interval property. For each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), assume we are given a closed interval \[I_n=[a_n,b_n]=\{x \in \mathbb{R}\;:\;a_n \leq x \leq b_n\}.\]

Assume also that \(I_n \supseteq I_{n+1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). Then the resulting nested sequence of closed intervals \[I_1 \supseteq I_2 \supseteq I_3 \supseteq \ldots\] has a nonempty intersection, that is \[\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}I_n \neq \varnothing.\]

Using (AoC) we will produce \({\color{red}x} \in \mathbb{R}\) so that \(x \in I_n\) for every \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). Then \[\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}I_n \supset \{x\} \neq \varnothing.\] Consider the set \(A=\{a_n\;:\; n \in \mathbb{N}\}\) of all left-hand endpoints of the intervals \(I_n\). Because the intervals are nested one sees that every \(b_n\) serves as an upper bound for \(A\). Thus by the (AoC) we are allowed to write \[x=\sup A\in \mathbb R.\] The proof will be complete if we show \(x \in I_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Since \(x\) is an upper bound for \(A\) thus \[a_n \leq x \qquad \text{ for all } \qquad n \in \mathbb{N}.\]

The fact that \(b_n\) is an upper bound for \(A\) and that \(x\) is the least upper bound implies

\[x\le b_n \qquad \text{ for all } \qquad n \in \mathbb{N}.\]

Thus \[a_n \leq x \leq b_n\] for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) hence \(x \in I_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and consequently \[x \in \bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}I_n.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Application 2 - Archimedian property of \(\mathbb{R}\)

Archimedian property.

Given any number \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) there exists \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) satisfying \[n>x.\]

Given any real number \(y>0\) there exists an \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) satisfying \[\frac{1}{n}<y.\]

Proof. Note that (ii) follows

from (i) by letting \(x=\frac{1}{y}\).

It suffices to prove (i).

Without loss of generality we can assume that \(x>0\) and consider \[A=\{nx\;:\;n \in \mathbb{N}\}.\] Suppose

for a contradiction that \(A\) is

bounded, i.e. there is \(y \geq 0\)

such that \(nx \leq y\) for any \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). This means that \(y\) is an upper bound for \(A\). By the (AoC): \[\alpha=\sup A \in \mathbb{R}.\]

Since \(x>0\), \(\alpha-x<\alpha\) and \(\alpha-x\) is not upper bound of \(A\). Thus we find \(m \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \[\alpha-x<mx \iff \alpha<(m+1)x.\]

This is contradiction since \(\alpha\) is the supremum of \(A\).

Corollary - \(\mathbb{Q}\) is dense in \(\mathbb{R}\)

\(\mathbb{Q}\) is dense in \(\mathbb{R}\). If \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(x<y\) then there is \(p \in \mathbb{Q}\) such that \(x<p<y\).

Proof. Since \(x<y\), by Archimedian property there is \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \[{\color{blue}n(y-x)>1}.\]

Then, we apply Archimedian property to find \(m_1,m_2 \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(m_1>nx \text{ and }m_2>-nx\). Then \(-m_2<nx<m_1.\)

Hence there is an integer \(m\) with \(-m_2 \leq m \leq m_1\) such that \[{\color{brown}m-1 \leq nx < m}.\]

We combine these inequalities to get \[\begin{aligned} {\color{brown}nx<m \leq nx+1}{\color{blue}<ny,} \qquad \text{ so } \qquad x < p=\frac{m}{n} < y. \end{aligned}\]

$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

More general

Theorem 1.4.5. For every real \(x>0\) and \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) there is a unique real number \(y>0\) such that \[y^n=x.\]

Proof: Uniqueness. The fact that there exists at most one such \(y\) is clear, since \(0<y_1<y_2\) implies \[y_1^n<y_2^n.\]

Identity \(b^n-a^n\)

In the proof (in the existence part), we will use the following identity

\[b^n-a^n=(b-a)(b^{n-1}+b^{n-2}a+\ldots + a^{n-2}b+a^{n-1})\].

which holds for all \(a,b \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Proof: Existence. Let \[E=\{t>0\;:\; t^n<x\}.\]

If \(t=\frac{x}{x+1}\), then \(0 \leq t<1\) hence \[t^n \leq t<x\] thus \(t \in E\) and \(E \neq \varnothing\).

If \(t>x+1\), then \(t^n>t>x\), so that \(t \not \in E\). Thus \(1+x\) is an upper bound of \(E\).

By the (AoC) we may write \(y=\sup E \in \mathbb{R}\). We will show that \[y^n=x.\]

It suffices to show that \(y^n<x\) and \(y^n>x\) cannot hold.

The identity \[b^n-a^n=(b-a)(b^{n-1}+b^{n-2}a+\ldots+ a^{n-2}b+a^{n-1})\] gives \[b^n-a^n<(b-a)nb^{n-1}\] if \(0<a<b\).

Assume \(y^n<x\). Choose \(0<h<1\) so that \[h<\frac{x-y^n}{n(y+1)^{n-1}}.\]

Put \(a=y\), \(b=y+h\). Then \[\begin{aligned} (y+h)^n-y^n<hn(y+h)^{n-1}<hn(y+1)^{n-1}<x-y^n. \end{aligned}\]

Thus \((y+h)^n<x\) and \(y+h \in E\). Since \(y+h>y\) this contradicts the fact that \(y\) is an upper bound of \(E\).

Assume that \(y^n>x\) and set \[k=\frac{y^n-x}{ny^{n-1}}.\]

Then \(0<k<y\). If \(t \geq y-k\) we conclude \[\begin{aligned} y^n-t^n \leq y^n-(y-k)^n<kny^{n-1}=y^n-x. \end{aligned}\]

Thus \(t^n>x\) and \(t \not\in E\). It follows that \(y-k\) is an upper bound of \(E\).

But \[y-k<y,\] which contradicts the fact that \(y\) is the least upper bound of \(E\).Hence \[y^n=x.\]

Corollary

Corollary. If \(a,b>0\) are real numbers and \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), then \[(ab)^{1/n}=a^{1/n}b^{1/n}\]

It is a consequence of the uniqueness property in the previous theorem.

\(x^y\) for \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\)

Fix \(b>1\).

If \(m,n,p,q \in \mathbb{Z}\), \(n,q>0\) and \(r=\frac{m}{n}=\frac{p}{q}\), then \[(b^m)^{\frac{1}{n}}=(b^p)^{\frac{1}{q}}.\]

Hence, it makes sense to define \(b^r=(b^{m})^{\frac{1}{n}}\).

If \(r,s \in \mathbb{Q}\), then \[b^{r+s}=b^rb^s.\]

If \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) define \[B(x)=\{b^t \;:\;t \in \mathbb{Q}, \, t \leq x\}.\]

Then \(b^n=\sup B(x)\) when \(r \in \mathbb{Q}\). Hence, it makes sense to define \[b^x=\sup B(x)\] for every \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Decimals

Decimals 1/2

Let \(x>0\) be real. Let \(n_0\) be the largest integer such that \(n_0 \leq x\).

Remark. Note that the existence of \(n_0\) follows from the Archimedian property. Why?

Then, we define \(n_1\) to be the largest integer such that \[n_0+\frac{n_1}{10} \leq x.\]

then, having \(n_0,n_1\), we define \(n_2\) to be the largest integer such that \[n_0+\frac{n_1}{10}+\frac{n_2}{100} \leq x.\]

We continue this procedure...

Decimals 2/2

Having chosen \[n_0,n_1,\ldots,n_{k-1}\] let \(n_k\) be the largest integer such that \[n_0+\frac{n_1}{10}+\frac{n_2}{10^2}+\ldots+\frac{n_k}{10^k} \leq x.\]

Let \[E=\{n_0+\frac{n_1}{10}+\frac{n_2}{10^2}+\ldots+\frac{n_k}{10^k}\;:\; k \in \mathbb{N}_0\}.\]

Then one can show that \(x=\sup E\).

Decimal system - example

Example. Write down \(0,25\) in the form \(\frac{n}{m}\).

Solution. We write \[0,25=\frac{2}{10}+\frac{5}{100}=\frac{20}{100}+\frac{5}{100}=\frac{25}{100}=\frac{1}{4}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example. Write down \(x=0,101010101\ldots\) in the form \(\frac{n}{m}\).

Solution. Note that \[10x=10,10101010\ldots,\] hence \[10x=10+x\]

\[9x=10 \iff x=\frac{10}{9}.\] $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

The extended real numbers system

The extended real number system

The extended real number system. The extended real number system consists of real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\) and two symbols \(+\infty\) and \(-\infty\).

We preserve the original order in \(\mathbb{R}\) and define \[-\infty<x<+\infty\] for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Example. If \(E \subseteq \mathbb{R}\), \(E \neq \varnothing\) but not bounded then \[\sup E=+\infty.\]

Properties of the extended real number system

Properties. If \(x\in \mathbb{R}\), then

\(x+\infty=\infty\), \(x-\infty=-\infty\), \(\frac{x}{+\infty}=\frac{x}{-\infty}=0\),

if \(x>0\), then \(x(+\infty)=+\infty\), \(x(-\infty)=-\infty\),

if \(x<0\), then \(x(+\infty)=-\infty\), \(x(-\infty)=+\infty\).